Started in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, this is the inaugural year of the Ramadan daily book share. Starting with recent reads, the booklist quickly shifted to formative influences. Back to the MRB.

Ramadan 1

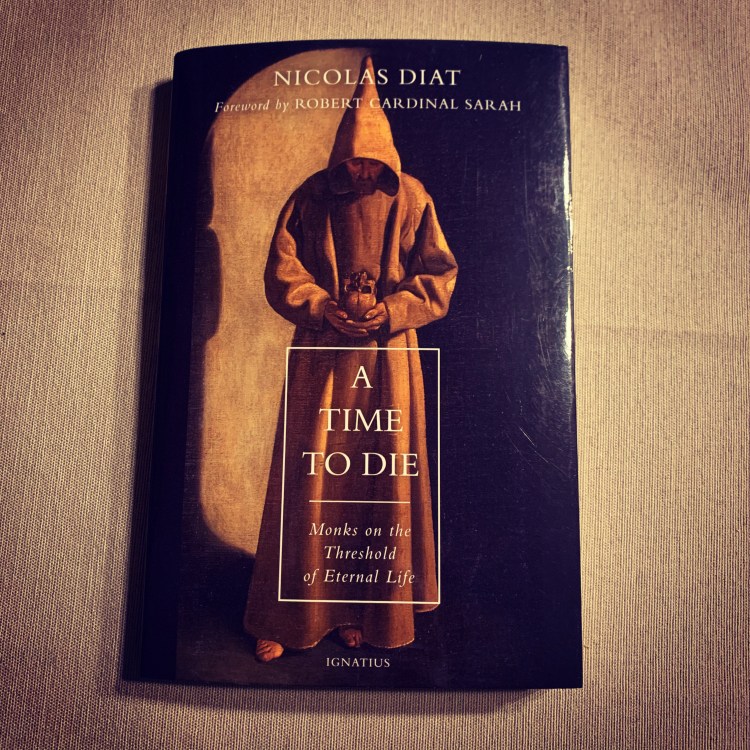

Ramadan has arrived in the midst of a disorienting time of pandemic. I’m not quite sure how I’ll manage it this year. Even before the month began I’ve been looking for grounding, which has been hard to come by. In an attempt to focus my energies during these days, I’m going to share each day something from my library. And for those of you who know me, you know that books- their very presence- have always figured prominently in my life. I would even say that my path of faith has been largely paved with them. With that in mind, I’ll endeavor to share something at least once a day, but I don’t really have a concrete plan yet. I’m sure I’ll share more on some days than others. At first I thought I’d just share the new-ish books that have come my way (and that’s how I’ll start), but I imagine I’ll turn to older volumes as well in order to pay homage to those works that have moved, changed, and shaped me in different ways. While it may not seem the most “religious” kind of expression, it strikes me now as quite apt given who I am. So here is the first, “A Time to Die: Monks on the Threshold of Eternal Life” by Nicolas Diat. Death has always commanded my attention and continues to inflect how I think and believe. In the midst of this pandemic, it’s presence has become all the more palpable. It was only natural then that I was drawn to a work that collects the varied meditations of monastics as they draw closer to their mortal ends. And so it begins. Ramadan 1

Ramadan 2-1

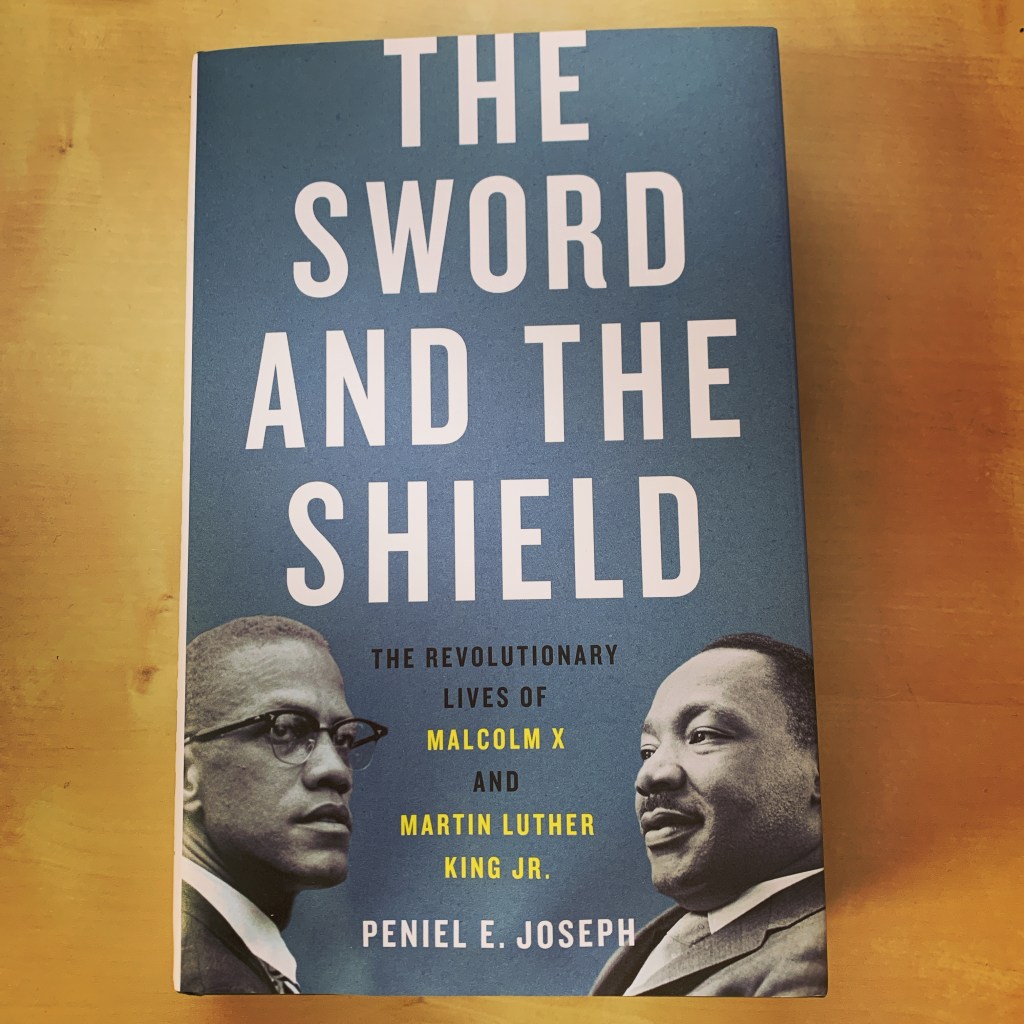

Malcolm X, in both his life and legacy, has long had a hold of my religious imagination. His presence is clear in my recent writings (the theological ones) and he continues to tower over what I’m writing now. I was eager then to get a hold of Peniel E. Joseph’s “The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.,” especially to read his new take on their meaning and relationship to one another. Looking forward to spending time once again with Malcolm X and Dr. King in the days to come. Ramadan 2

Ramadan 2-2

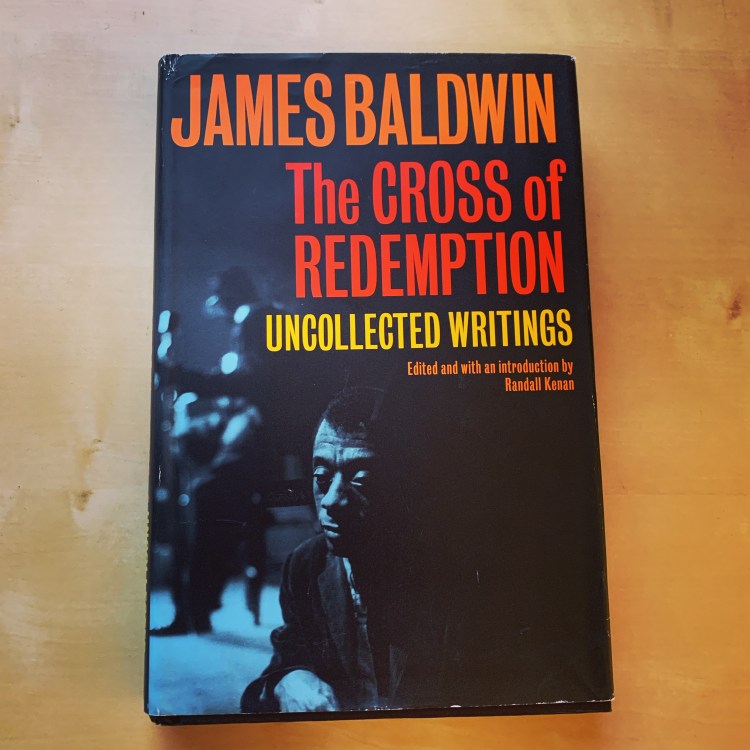

Only day 2 and I feel compelled to do a double header already. It somehow seemed wrong to spotlight a work on Malcolm X and Dr. King and not also mention Baldwin. So I wanted to share my most recent acquisition in that vein, “James Baldwin: The Cross of Redemption, Uncollected Writings” edited by Randall Kenan. While I obtained it several months ago I still recall how I first learned of it. I spotted the spine of this book in a photo used for the bookmark of an amazing New Haven bookstore and community space called People Get Ready. Not having heard of this particular collection, I sought it out. While not from that volume there is a poignant and powerful letter he wrote to his nephew with which I’d like to conclude. I’ll leave you with words quoted therein that still reverberate with me now as much as when I first heard them: “The very first time I thought I was lost, my dungeon shook and my chains fell off.” I’m hoping this entices you seek out that letter if not more from Baldwin’s world of words. Ramadan 2, the second

Ramadan 3

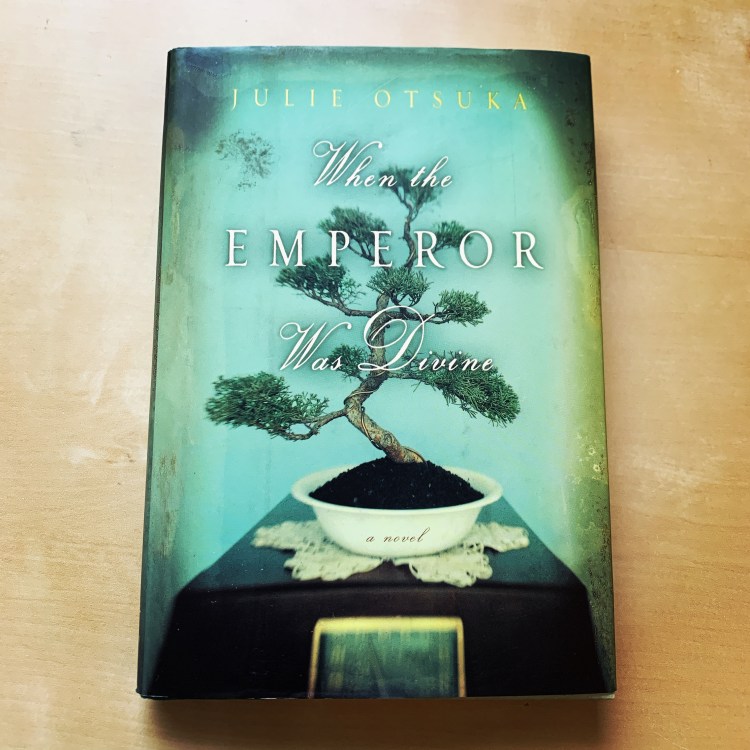

This is one of the last books I purchased from a used bookstore before the pandemic closed them all down. While browsing in Books and Company in Hamden I came across this work by Julie Otsuka, “When the Emperor was Divine.” I had heard of Otsuka before so I was happy to find this. The novel follows the experience of a Japanese American family subjected to American internment during World War II. The work is brief, but Otsuka paints an evocative and haunting picture with an economy of words. The namelessness of the family only serves to accentuate the story’s poignancy. This dark episode of American history (of so many dark episodes) is one that has long stayed with me from when I first learned about it when I was young. It brought home for me what it means to be Asian in this country. Ramadan 3

Ramadan 4

“The Jealous: A Sufi Mystery” by Laury Silvers is the sequel to her first book “The Lover.” Alas, the first book is on loan to a friend, otherwise I would have photographed them together. While I have not read this one yet, my hopes are high given how well the first book delivered. In that work, as the story unfolds, the medieval city of Baghdad is evocatively brought to life. There is an admirable fidelity to history deftly woven into the narratives. As a Muslim reader, this was especially rewarding, though history aficionados of all stripes should be similarly pleased. When this sequel was released back when things began to shut down (so many weeks ago) I knew we had to add it to our reading list. Ramadan 4

Ramadan 5

On March 28, 2020 William Helmreich died from COVID-19 at the age of 72. Notices on social media brought his tragic passing to my attention. Until those headlines appeared on my screen I had not heard of him, much to my embarrassment and regret. Helmreich was a professor of sociology at the City College of New York. During his life, he had been prolific writing on a broad number of subjects. The book that I’m sharing here, “The New York Nobody Knows: Walking 6000 Miles in the City,” is one I picked up after learning of his unfortunate death. I was drawn to it given the significance that New York City has had in my life and continues to have for my family. Indeed, my brother and parents continue to weather the pandemic storm tearing through it. The book is an intimate study of New York neighborhood-by-neighborhood, block-by-block. Over the course of four years he methodically walked some 6,000 miles of New York City in order to experience every corner of the five boroughs. As described on the back of the book, this endeavor was long in the making. “As a child growing up in Manhattan, William Helmreich played a game with his father called ‘Last Stop.’ They would pick a subway line, ride it to its final destination, and explore the neighborhood. Decades later, his love of exploring the city is as strong as ever.” While the book appears to be a study aimed at giving voice to all those who inhabit the city in as rich, diverse, and authentic way as possible, the book’s description brought to mind other beloved works of a related spirit, even if they differ in form, concern, or arc – works like John Freely’s “Strolling Through Istanbul: A Guide to the City,” George R. Stewart’s “Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States,” and Jean Jacob’s “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.” It even brings to mind the N.K. Jemisin novel I’m presently reading “The City We Became,” which brings the boroughs of the city to life in a stunningly remarkable and imaginative way. Although I come late to Helmreich’s work, I thought reading his book would be a proper way to pay my respects to his recent departure from this life and this world. Ramadan 5

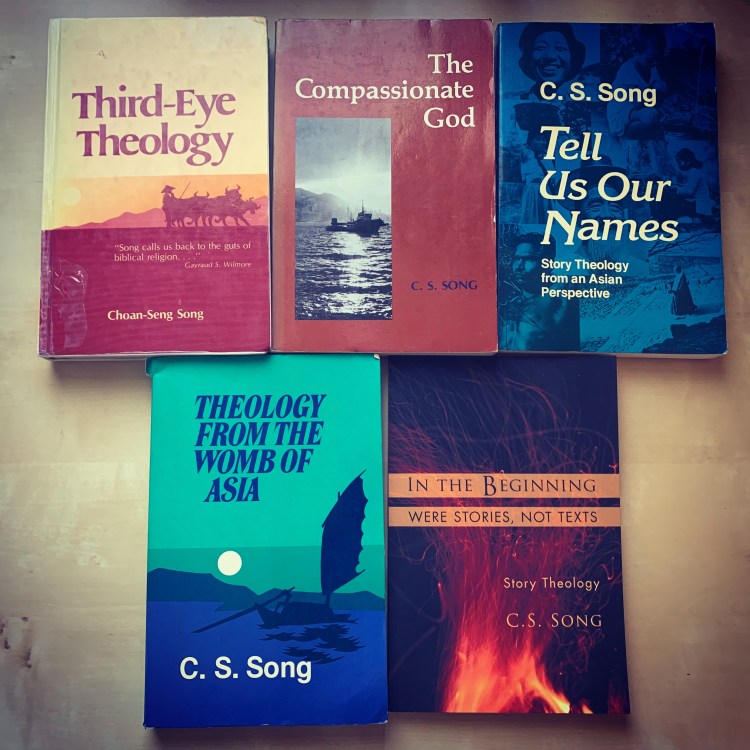

Ramadan 6

I still consider myself a novice when it comes to Christian theology. While I have benefited greatly from my encounters with different contemporary Christian theological projects, the field is so vast I have no illusion that I am continually only scratching the surface. I still discover voices and works that I feel I should have known about earlier. I realize of course, that these are not the waters, so to speak, that I swim in, but I believe there is much insight and joy to be had from plumbing those depths as an outsider. In fact, while reading various Asian theological writings, I kept coming across references to an Asian American theologian that I did not recognize, Choan-Seng Song. Curious about his mention, I discovered that C.S. Song has been and continues to be a prolific writer who sought relatively early on to challenge the Eurocentrism of Christian theology and to imagine it through an array of Asian resources. Since that initial chance inquiry, I’ve felt compelled to bring myself up to speed. Here are some of his works that I’ve added to the library: Third-Eye Theology (1979), The Compassionate God (1982), Tell Us Our Names: Story Theology from an Asian Perspective (1984), Theology from the Womb of Asia (1986), and In the Beginning Were Stories, Not Texts: Story Theology (2011). While I still have more to comb through here (as always), what I’ve read thus far with respect to story, imagination, and theology has already been incredibly fruitful. Ramadan 6

Ramadan 7

Over a year ago, a colleague lent me this book of poetry after I stopped by her office to talk about some other University matter. Somehow our conversation took a turn for the better (since University matters are rarely ever a joy) which is when she suggested and lent me the following, Fatimah Asghar’s “If They Come For Us.” Worry not, this is not a lent copy that I’ve held onto for more than a year. I’m not that type of person (and you shouldn’t be either). After reading only a few of the poems I knew I would eventually have to seek out my own copy. And so here it is. I have little talent for poetry, though I wish I did. Poetry is an art that seems to lie above and beyond me. I still greatly appreciate it nonetheless. As for this work, the poems within are each memorable, creative, and incisive in their own ways, but when read altogether they form a striking narrative of life that is both intimately personal and evocatively encompassing of the experience of so many others. Ramadan 7

Ramadan 8

Yesterday I shared a powerful collection of poetry by Pakistani American Fatimah Ashgar. Today I return with one that I’ve just recently received by Vietnamese American poet Thanhha Lai. The book is aimed at young adults (hence the Newbery Honor), but let that not be a discouragement. It is an engaging and evocative collection. I can’t quite recall how I discovered “Inside Out & Back Again,” but it was likely while I’ve been researching the experience of refugees from the end of the American War in Vietnam. In fact, the reason I’m sharing this one now is to honor my mother, whose birthday is today. I’ve been spending time trying to piece together what life was like for her in Vietnam, but her recollections have been reticent and fragmentary, perhaps with good cause. What Lai offers here are poems drawn from her own experiences before, during, and after the fall of South Vietnam. While the poet was half my mother’s age at the time of the war’s end in 1975, her series of carefully crafted poems offer a precious glimpse into that turbulent span of time into which I’ve been struggling to find a window. Sometimes heavy, sometimes light from what I’ve read thus far, the work is shaping up to be a memorable “novel in verse” as one reviewer so aptly put it. Ramadan 8

Ramadan 9

Today I’ll begin to shift from covering books that I’ve recently acquired (relatively speaking) to works that have been deeply influential or formative for me in one way or another. Today and tomorrow I’ll start with who I consider two of the most important writers for my present outlook and endeavors (though there are many, many others who’ll I’ll try to feature here later in this holy month). I would be remiss not to begin with Hans-Georg Gadamer (d. 2002), the prominent German philosopher. I was first introduced to Gadamer during my time pursuing my Masters in Theological Studies at Harvard Divinity School. On a whim, I enrolled in a survey course called “Theology and Hermeneutics,” while not having any inkling what the word “hermeneutics” actually meant. In that class we read a small portion of Gadamer’s magnum opus “Truth and Method.” Reading that brief passage was enough. Those few assigned pages exploded my horizons. It opened my mind in incredible ways. Gadamer’s articulation of hermeneutics quickly became a constant touchstone as my studies progressed. I purchased the book that same semester and would spend the next half decade (and more) working through the text keeping the hefty volume constantly by my side. It traveled with me everywhere. In the end, it became an important theoretical framework for my dissertation on al-Qushayri and his Qur’an commentary. It was sad, then, to have to cut that section from the book that the dissertation eventually became. I even remember running across a German edition of the work in which it was originally written (also pictured here) at a used bookstore in Cambridge and felt compelled to buy it, knowing full well that I’d hardly ever reference it. Of course, I’ve moved beyond Gadamer since then, but my thinking now (especially about tradition) still owes much to his understanding of hermeneutics. Ramadan 9

Ramadan 10

Gadamer may have opened my mind, but it was the Swiss Reformed theologian Karl Barth (d. 1968) who shook my heart and planted the seeds for my future work in theology. For that, I shall long be grateful. In that same semester where I encountered Gadamer, I also read an excerpt from Barth’s “Epistle to the Romans.” I bought the book immediately. Within the Christian theological world, Barth is well known. His reach and the reactions to him have been unquestionably extensive. Though Muslim I consider myself – in a way – a Barthian of sorts. I know, it is an odd thing for me to say. Of course, I do not subscribe to the theological content of Barth in all its of Christ-centricity. What I am mainly moved by and what I have taken to heart is the mode and method of his theological delivery. When I first read this book I had never read a work like this. It spoke thunderously. It spoke with unrelenting and unapologetic faithfulness, which until that point I had rarely encountered in the academy and even then, never with this magnitude of incisive eloquence. The deeply homiletic tone of that work, written while Barth was a pastor, was one reason that I found the book so gripping. But another reason I am drawn to Barth is his uncompromising commitment to revelation. His treatment is like nothing I had encountered before. It is breathtaking to read. So where my views on tradition were first influenced by Gadamer, my views on revelation were first prompted – in a serious way – by Barth. And when I eventually came to write theology myself, Barth remained on my mind as I sought to develop my own distinct voice. In fact, this is why “Modern Muslim Theology” took me so long to see the light of day. The book was long done, but editors would press me to remove the very voice that ran through its core, and I would refuse to change it leading to rejection. I am immensely thankful, then, for the press that understood. Finally, in featuring “The Epistle to the Romans” I could not help but foreground it in front of the so-called “white elephant” that is Barth’s voluminous, yet unfinished masterpiece “Church Dogmatics” (my edition, including index, runs to 14 volumes). Ramadan 10

Ramadan 11

Of course, at some point Ibn al-‘Arabi (d. 638/1240) was going to show up. I decided to start with my first encounter with al-Shaykh al-Akbar, “the Greatest Master,” or as Anne-Marie Schimmel once called him the Magister Magnus. Back during my undergraduate years I was a religious studies major thanks to an initial course called “Islam in the Classical Age” taught by Abdulaziz Sachedina. Unsurprisingly, that would not be my last class on Islam. Soon enough, I took Sufism (perhaps my second or third Islam course) in which an excerpt from William Chittick’s “The Sufi Path of Knowledge” was assigned. I’m fairly certain my habit of buying the books of selections assigned in my course readers began back in these days thanks to courses like this. As for “The Sufi Path of Knowledge,” the book offered extensive translated excerpts from Ibn al-‘Arabi’s magnum opus Futuhat al-Makkiyya (“The Meccan Openings”), which remains for me a dizzying work even after all these years. Reading the work has always required a great deal of patience and investment. It is not an easy text to get through. It also requires immense imagination, which is perhaps why I am drawn to Ibn al-‘Arabi’s religious thought in the first place and why the imagination continues to hold such a high place in my own thinking. Time and again, his works have proven a source of inspiration, beauty, and insight. And although questions will always remain for me (as they should), I welcome those opportunities to revisit his array of ideas in all of their bewildering intricacy. Were it not for Ibn al-‘Arabi, I would not have dwelled so long or lovingly on the religious imagination and all that it seeks to encompass. Ramadan 11

Ramadan 12

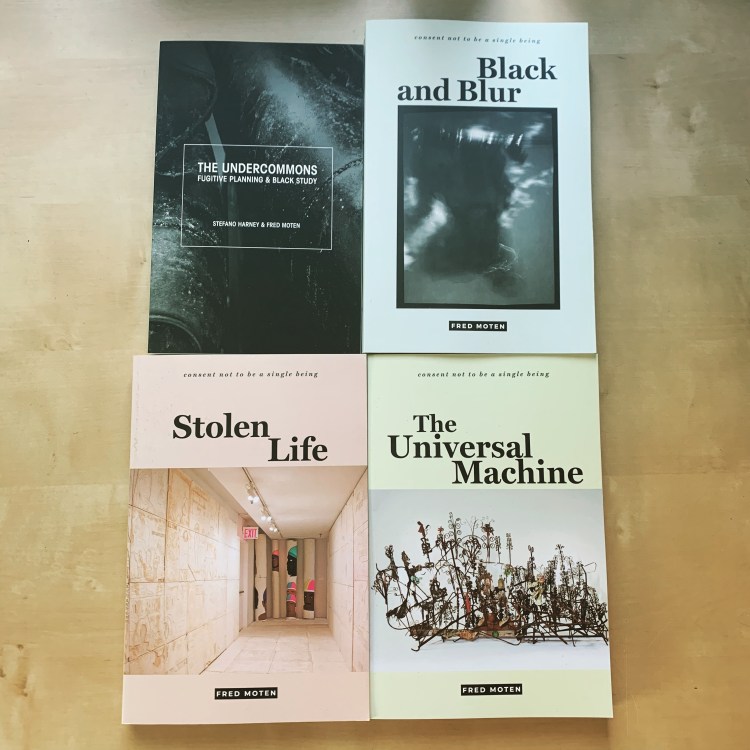

At least in my head, the best way to follow up on Ibn al-‘Arabi is to turn next to Fred Moten, Professor of Performance Studies at NYU as well as an accomplished poet and noted scholar of black studies and critical theory. There are quite a few contemporary, living thinkers today that I might choose to follow Ibn al-‘Arabi. Consider the many philosophers and theologians of our day who have developed incredibly sophisticated systems of thought and modes of analysis as well as equally impressive and often idiosyncratic lexicons in support of them. Moten is certainly amongst this select crowd. His body of work, radical and interventionist in energy and spirit, continually grows and I’m finding it hard to keep apace (I have yet to really dive into the trilogy herein). And like so many others, I find it takes great patience and commitment to unpack his writings (and even then, that’s not always enough). Yet, what I find particularly acute in the case of Moten, is the immense sense of both joy and awe that accompany my forays into his works. Naturally, my choice of Moten is quite personal. I am drawn to critical engagements with race and resistance and he undertakes both with distinctive brilliance. Now, I’ll also be the first to admit, I don’t get everything that he discloses. I simply lack the cultural and literary range that his horizon of words encompasses (it is vast) and there is artistry in his delivery that is difficult for me to unravel at times, but what I do glean is always incisive and worthwhile. It dwells long on my mind afterwards, it prompts much needed shifts in my perspective, and it often compels changes in the vectors of my thinking and acting. Fred Moten’s “The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study,” written with his longtime collaborator Stefano Harney, is a good starting point. Moten’s trilogy “consent not to be a single being” appeared more recently from 2017-18: Black and Blur (1), Stolen Life (2), and The Universal Machine (3). Ramadan 12

Ramadan 13

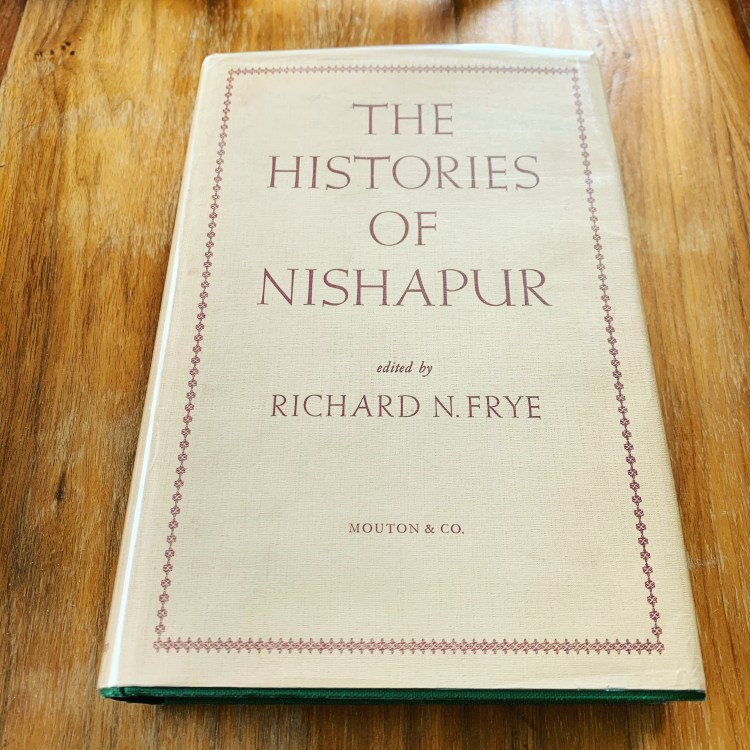

Here is a volume that honestly isn’t an influence, but represents, nonetheless, a welcome companion during the early years of my scholarly career. “The Histories of Nishapur,” edited by Richard N. Frye (d. 2014), collects three manuscripts in facsimile (one in Persian, two in Arabic) that document the lives of the religious scholars and personalities who lived in medieval Nishapur. I was particularly interested in the latter two manuscripts as I endeavored to map out the social networks that surrounded the life of the Nishapuri scholar and sage Abu al-Qasim al-Qushayri (d.465/1072). For months and years on end, the hefty volume either sat on the shelf of my study carrel in Widener Library or lay on my desk at home – both places where I slowly chipped away at the dissertation. That book, of course, was the library’s copy. After I completed the dissertation, I knew I would still need access to this work while I revised it for eventual publication as a book. Before graduation, I spent a good amount of time tediously scanning the entire volume, but the image quality of the photographed manuscript pages was significantly degraded. A year later, I resolved to obtain a copy for myself, despite its rarity and cost. While my work has moved on since that time, I am glad it remains in my company. The original order slip for the book remains tucked inside. It appears that on May 18, 2010 I purchased online the book from Powells in Portland, Oregon, a famed used bookstore that I have yet to visit in person and which – as the news reports – is severely struggling amidst the extended closures precipitated by the current pandemic. Unfortunately, it seems I may never get my chance to see it in person if indeed Powells is forced to shutter permanently in the near future. Ramadan 13

Ramadan 14

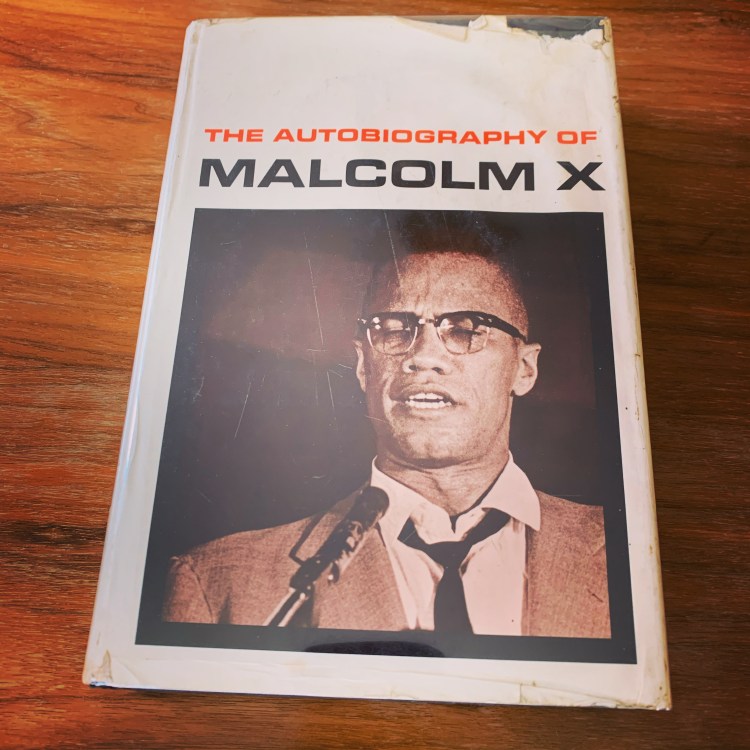

It should be no surprise that I would eventually feature “The Autobiography of Malcolm X.” The influence of el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, Malcolm X (d. 1965), has been extensive and enduring. The literature that has arisen around him and the cultural swells that have emerged from out of his legacy are manifold. Personally, I’ve revisited this particular work by Malcolm X and Alex Haley many times over. It is assigned regularly every year in my classes. I drew upon it at length in my last book. In fact, Malcolm X continues to figure significantly in my present work. It is his provocative discussions of both race and faith – his critiques of society and religion together – that continue to engage and animate me. With that said, consider this post on Malcolm X the first in a four-part series of what I consider a sequential (and quite consequential) set of influences on my trajectory of thinking and being. As for the book itself, this copy is the earliest edition of the autobiography that I own, a fourth printing. While not a first edition (the search continues), I consider this one of my more fortuitous finds and probably the best five dollars I’ve ever spent (used bookstores are a treasure by the way). Whenever I reference the “Autobiography of the Malcolm X” in my writing, I cite this particular printing, since it is the closest thing to the original publication that I own – its pagination matches the first edition unlike some later editions. It seems appropriate today to end on some words from Malcolm X: “Mankind’s history has proven from one era to another that the true criterion of leadership is spiritual. Men are attracted by spirit. By power, men are forced. Love is engendered by spirit. By power, anxieties are created. I am in agreement one hundred percent with those racists who say no government law ever can force brotherhood. The only true world solution today is governments guided by true religion – of the spirit.” (p. 375) Ramadan 14

Ramadan 15

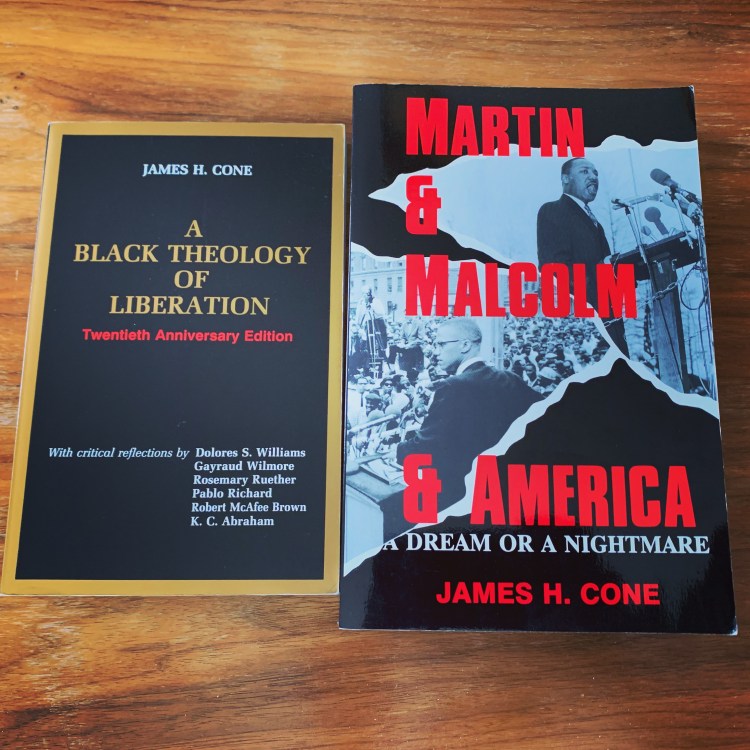

Yesterday I began with Malcolm X, today I turn to James Cone. I first encountered Cone during my Master’s when we read a part of “A Black Theology of Liberation.” I felt compelled to read the book in its entirety shortly thereafter. The book was eye opening. Cone showed me that theology need not be overly scholastic and philosophically abstract. Rather, theology could be done in a radically different way than how I had encountered it previously. He was developing, in this book, a form of theology, or perhaps delineating an arc of it, that was charged with a deep sense of both faith and justice while also being grounded in the gritty and difficult concreteness of our social realities. I would go on to read many of his other works, but the one that still stands out as the most significant and enduring for me is the other book that I’m sharing here, “Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare.” While there are many treatments of Malcolm X that have appeared, this work was the first that I had encountered that sought to take him seriously as a religious voice because here was a Christian theologian placing Malcolm X, the Muslim minister, in critical conversation with Dr. King, the Baptist Reverend. It was in the midst this particular book that I realized that I deeply wanted to read engagements with Malcolm X from distinctly Muslim vantages. Ramadan 15

Ramadan 16

Like “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” Sherman Jackson’s “Islam & the Problem of Black Suffering” has become a staple in my life. It serves as one of the core texts for the Islamic theology course that I teach every year. As a result, I revisit it regularly. I remember first reading it back in 2009. In the introduction, I found Jackson engaging with the broader world of black theology, which is overwhelmingly Christian in character, as well as those who sought to critique and challenge it, particularly William R. Jones and his book “Is God a White Racist?” This was the sort of exchange for which I had long been looking. In the rest of the book, Jackson dove into the past of the classical Islamic tradition. The move, however, was not purely historical. Ultimately, Jackson was imagining for the present how four theological schools (the Mu’tazila, Ashʿaris, Maturidis, and Hanbali traditionalists) would answer more contemporary concerns, namely the titular problem of black suffering. His exploration sought to develop responses constructed from classical methodologies and frameworks. While, his treatment is not comprehensive of the tradition, I saw the work as an important step in the right direction. In many ways, I took the book as an invitation – if not a challenge – for Muslims more broadly to imagine for themselves how the dilemmas, concerns, and crises of the present might be met from their respective horizons of faith and being. Ramadan 16

Ramadan 17

As mentioned earlier, I’ve envisioned this post and the previous three as constituting a sequential series of sorts. It was while I was reading Jackson’s other work on Black Religion and theology, “Islam and the Blackamerican: Looking Toward the Third Resurrection” that I happened across the present work. Jackson’s discussion of global white supremacy prompted me to finally read this classic work, “The Racial Contract” by Charles W. Mills. Building upon the notion of the social contract, Mills builds out the racial contract as an insidious, underlying global structure that he systematically and witheringly lays bare in this brief, but powerful work. It is a resounding critique that shares in many ways the same fire found in the words of Malcolm X. As I write on race now, Mills’ book, as well as those by Jackson and Cone, seem always close at hand. And as I look out at the world today, their relevance seems far from diminished – they remain necessary. Ramadan 17

Ramadan 18

Looking back, I am finding that the books and authors that I appreciate the most are those that open up to me new possibilities – works that drive me to look at things, myself included, differently. Today, I am sharing Gloria Anzaldúa’s “Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza” because her work revealed to me that a book did not have to look or speak like what others expected it to be. Its form did not need to conform to the strictures of others’ overbearing structures. It did not even need to restrict itself to a single language or expressive mode, especially when we ourselves are not bound, formed, or alive in such a limited way. It is also a work that gifted me with a different sense of home, one not delimited by borders. With that, allow me to end with a few words from Anzaldúa herself: “Borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge. A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition. The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants. Los atravesados live here: the squint-eyed, the perverse, the queer, the troublesome, the mongrel, the mulato, the half-breed, the half dead; in short, those who cross over, pass over, or go through the confines of the ‘normal.’” (p. 25) Ramadan 18

Ramadan 19

During my undergraduate years I was exposed to Muhammad Iqbal’s (d. 1938) “The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam.” This encounter coincided with my fascination with the Western philosophical tradition, which only made the text all the more engaging. I have continued revisiting Iqbal, including what poetry of his that has been translated, in the years since. While my reading of him has naturally shifted and changed over time, the original resonance of his project has remained an enduring thread in my thinking. My first copy of the book – purchased those many years ago – rests to the left. On the right, is the 2012 republication of the work by Stanford University Press, which has become the one I reference for citations. Let us end with a bit of Iqbal: “When attracted by the forces around him, man has the power to shape and direct them; when thwarted by them, he has the capacity to build a much vaster world in the depths of his own inner being, wherein he discovers sources of infinite joy and inspiration. Hard his lot and frail his being, like a rose-leaf, yet no form of reality is so powerful, so inspiring, and so beautiful as the spirit of man! Thus in his inmost being man, as conceived by the Qur’an, is a creative activity, an ascending spirit who, in his onward march, rises from one state of being to another: ‘But Nay! I swear by the sunset’s redness and by the night and its gatherings and by the moon when at her full, that from state to state shall ye be surely carried onward (84:16-19).’” (p. 10) Ramadan 19

Ramadan 20

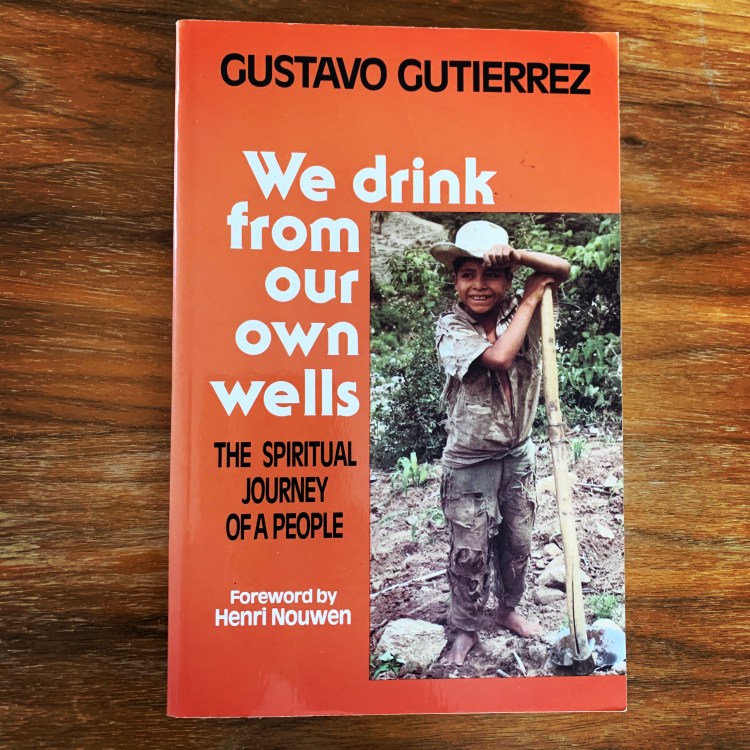

Here’s another relatively recent acquisition that I had overlooked from earlier. One of the things I miss about the building where my office is located are the random books that I’ve found there. Every so often, my colleagues end up cleaning their offices by purging old papers and their unwanted books. Inevitably, those books get deposited on a fairly sizeable “free” bookshelf in the hallway for all to peruse. Just days before the closure of campus, I found this book resting alongside a hundred others, “We Drink From Our Own Wells: The Spiritual Journey of a People” by liberation theologian Gustavo Gutierrez. While familiar with his work, this was one that I had not yet read – an exploration of Christian spirituality among the communities of Latin America. Glad to have it on my ever increasing to-read list. While I’ve never found my campus office conducive for work or writing (home and cafes are my preference), there is much else – in addition to book finds – that I do miss about that shared space and all the people therein. Ramadan 20

Ramadan 21

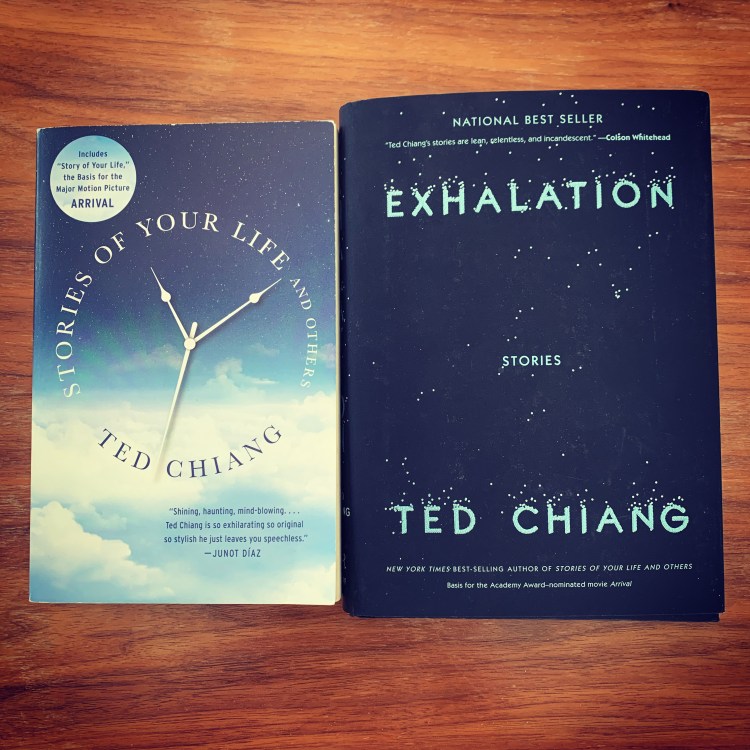

This is a post that serves a double purpose, it features a personal influence while also marking a recent purchase that I’m currently reading, all by the same writer, Ted Chiang. The book on the left is Chiang’s “Stories of Your Life and Others.” I picked up this collection of speculative fiction after I learned that one of my favorite movies “Arrival” was based on a short story contained within, the titular “Stories of Your Life.” I was not disappointed when I read that piece or the volume in its entirety. There is a capaciousness to Chiang’s imagination that I find stunning and visionary. Usually, I encounter this during the long unfolding of book-length narrative or even cycle of books (as with N.K. Jemisin’s “Broken Earth” series). I did not expect, then, to experience this degree of wonder in a collection of fictive vignettes. While I have always appreciated short stories, it was while reading Chiang that I realized how weighty a well-crafted concise narrative could be. I consider him one of my inspirations for my experiment in writing brief narratives. In fact, the short pieces I’ve shared on Facebook are the result of this ongoing endeavor. It was also while reading this first book that I learned that Chiang is something of a perfectionist who is never satisfied with his work. I figured it would be some time before his next collection would come out. Thus, when “Exhalation” was announced I pre-ordered it right away. I plan to start it today, insha’Allah. Ramadan 21

Ramadan 22

Is this sort of a cheat? Yeah, kind of. Is it also a way for me to talk about food while fasting? Of course! So to be honest, I don’t really count this cookbook, “Momofuku” by David Chang and Peter Meehan, as a significant influence, but I do have great respect for the Korean American chef behind the work, David Chang and his willingness to rethink ideas and challenge problematic conventions. I imagine this might be why, at least in part, the late Anthony Bourdain (who I also immensely respect) was prescient enough to support Chang early on in his career. As for the cookbook, it unsurprisingly delivers a wide array of recipes collected from across his growing string of restaurants: Momofuku Noodle Bar, Ssäm Bar, Ko, and so on, which alone is worth the price of entry. (As an aside, I need to say there needs to be far more ramen and friend chicken joints in the world like Noodle Bar. Thank you Bantam King for going halal last Ramadan – the ummah salutes you!) What I found most interesting, however, are the autobiographical bits that Chang liberally peppers throughout the text. When this year’s fasting is over, I would recommend watching Chang’s Netflix series “Ugly Delicious” as well as season one of PBS’s “Mind of Chef,” which preceded it. That first season, which Bourdain produced, focused solely on Chang and his culinary craft. And if somehow all of that wasn’t enough, Chang hosts his own podcast as well, but that is likely a level of commitment that only the most ardent or foolish would undertake (I’ve listened to a few…). As for the future, I was delighted to discover that Chang has a proper book coming out this fall, “Eat a Peach: A Memoir.” Here’s to Asian American creativity. Ramadan 22

Ramadan 23-1

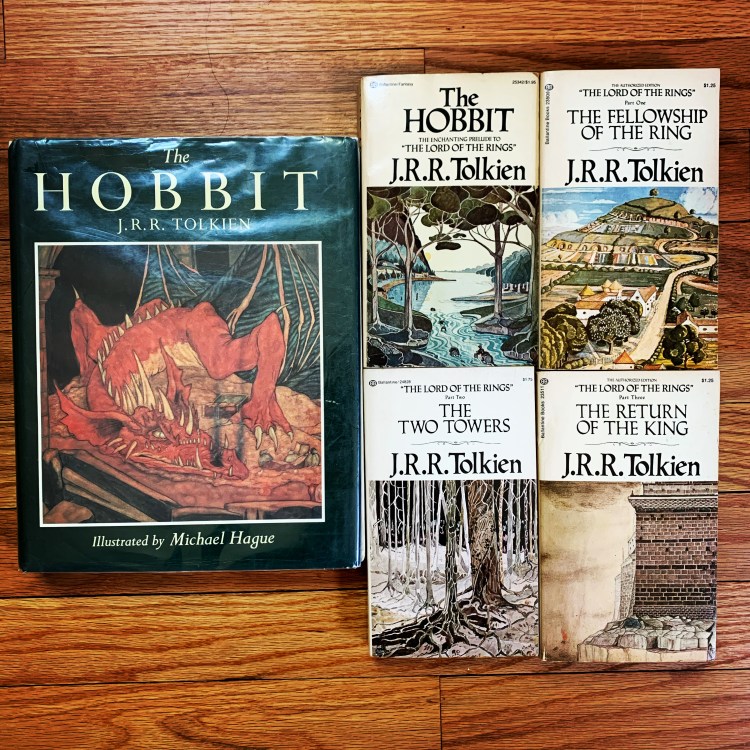

With the next author, I wanted to wait until the weekend so I could spread the love over three posts.. Part 1: My reflections thus far have taken me as far back as my undergraduate years. With the works of J.R.R. Tolkien (d. 1973), however, I’m taken back to my childhood many years prior. I first encountered “The Hobbit” as a young child when I borrowed this large illustrated hardback copy of the book from my library. I checked it out on numerous occasions pouring over that story many times over. Years later in high school, I found that same exact copy sitting on the library sale shelf. I bought it for the exorbitant 50 cents that they were asking and have held onto it since (pictured not the left). The tale within was gripping for my young mind – it was about adventure and dragons after all. Then, a bit later, on a visit to my older cousins in Massachusetts, I discovered that there was a trilogy of books that followed it: “The Fellowship of the Ring,” “The Two Towers,” and “The Return of the King.” They very generously leant me their paperback copies, which I treasured greatly, at least for the time that I had them. I read them so much – or tried to – that the cover fell of the first book. I recall carefully taping it back on and sheepishly returning it in that sad pitiful state (since then, I’ve gotten these paperbacks on the right – all of which feature Tolkien’s own illustrations on the cover). And yes, the best I could do back then was to “try” and read them. While “The Hobbit” had been relatively accessibly, the prose of the Lord of the Rings proved to be much too dense for me. There were so many names, odd lines of puzzling poetry and song here and there, and obscure descriptions that just waxed on for far too long – all too much for my young mind to plow through and absorb. Despite my incomprehension, I realized that there was something special here nonetheless – that an epic saga followed that first whimsical adventure and more than that I sensed that an immensely rich world lay beneath and behind it all. Of course, it eventually clicked not long after and laid an immovable hold over me. It was during my encounter with this cycle of books by Tolkien that I discovered the wonders of world-building, though I didn’t know what to call it back then. Ramadan 23, the first of three

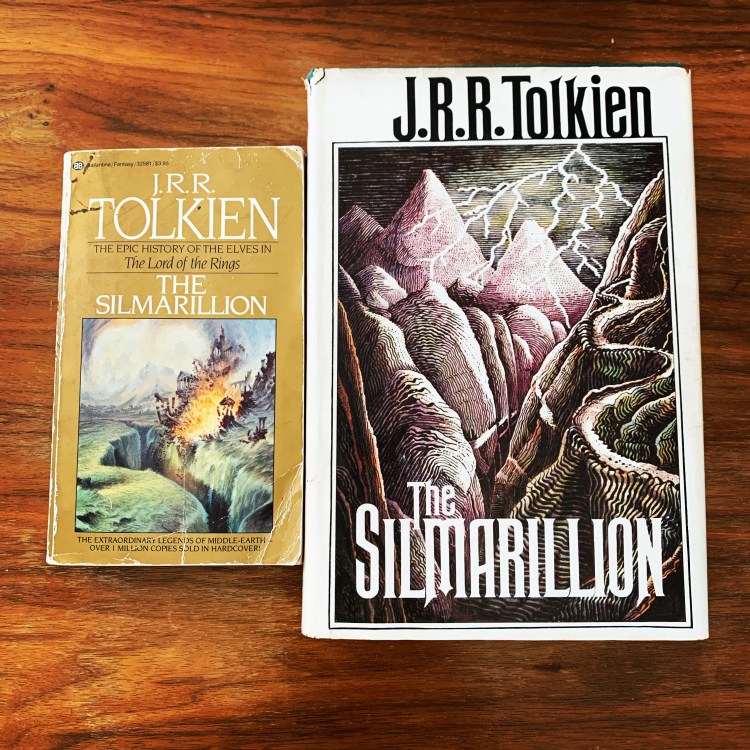

Ramadan 23-2

Part 2: The depth and breadth of Tolkien’s world-building was not fully apparent to me until I discovered “The Silmarillion,” written by J.R.R. Tolkien, but collected, edited, and posthumously published by his son Christopher Tolkien (d. 2020). My original copy looked exactly like the one on the left, but I foolishly got rid of it years ago (oh the recklessness of youth!). The version on the right is a fourth printing of the first American edition. While I eventually learned to read and appreciate the Lord of the Rings trilogy, “The Silmarillion” took much longer for me to properly grasp. My first few attempts during my early teenage years were an abysmal failure because I didn’t realize at the time what this work really was – Tolkien’s lifelong endeavor to craft a world with an expansive and intricate history for the lands of Middle-Earth. Moreover, all of this was built upon the richly imagined matrix of languages of Tolkien’s own making. He was, after all, a philologist at heart. I had entered expecting another novel, not realizing that it was a work of myth-making and as myth-making it was constantly evolving and shifting in his mind and for that world. As a result, I can read this book now with much greater appreciation finding it a beautifully told saga, full of tragedy and artistry. Indeed, I owe this book much. Before I even had an inkling of becoming an academic, I threw myself into my own attempts at world-building as a youth, directly inspired by Tolkien’s works, imagining worlds, pasts, and peoples with excruciating detail, but with admittedly less poetry and erudition. I did so through the stories that I penned, the games that I designed, and the art that I created (side note: I used to draw constantly and even entered college intending to be an Art major much to my parents’ chagrin). Only more recently in life have I realized how all of this imaginative labor – and I think labor is the right word here – prepared me so well for the scholarly personality that I would eventually develop and assume. “World-building,” so to speak, has never left me. Ramadan 23, the second of three

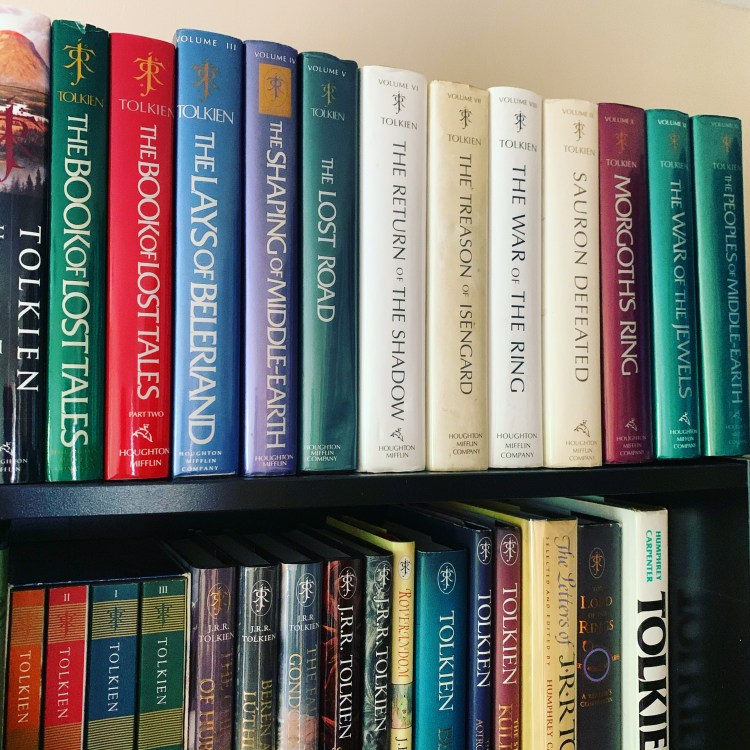

Ramadan 23-3

Part 3: As many bibliophiles are inclined to do, I own my fair share of multivolume sets. It seems almost a pre-requisite for those of us working on classical Arabic works. But the ur-set for me has always been the 12-volume “History of Middle-Earth” edited by Christopher Tolkien. From 1983 to 1996, Christopher Tolkien painstakingly gathered and arranged the many drafts, notes, and unfinished tales left by his father in order document J.R.R. Tolkien’s literary legacy, at least with respect to this imagined world. I remember my younger self standing in front of the bookstore shelves admiring this series as it grew volume by volume with the passing years. At the same time, I was also discouraged by the cost of it all and my recent difficulties with “The Silmarillion” did not help either. And so I withheld. Nonetheless, what the series represented to me back then was a fuller picture of Tolkien’s horizon-spanning vision of the world that he had created. It seemed to offer an intimate look into how his books came into being. Thus, when I finally had the means to slowly acquire the set, I did. Now all that remains is to find the time to read them all, which seems even harder to come by. With that, these past three posts are my homage to Tolkien, who not only created a world with great care, but who also chose to share it with the rest of us. I am grateful and indebted to the world-building that he introduced to my mind all those many years ago. Ramadan 23, the third of three

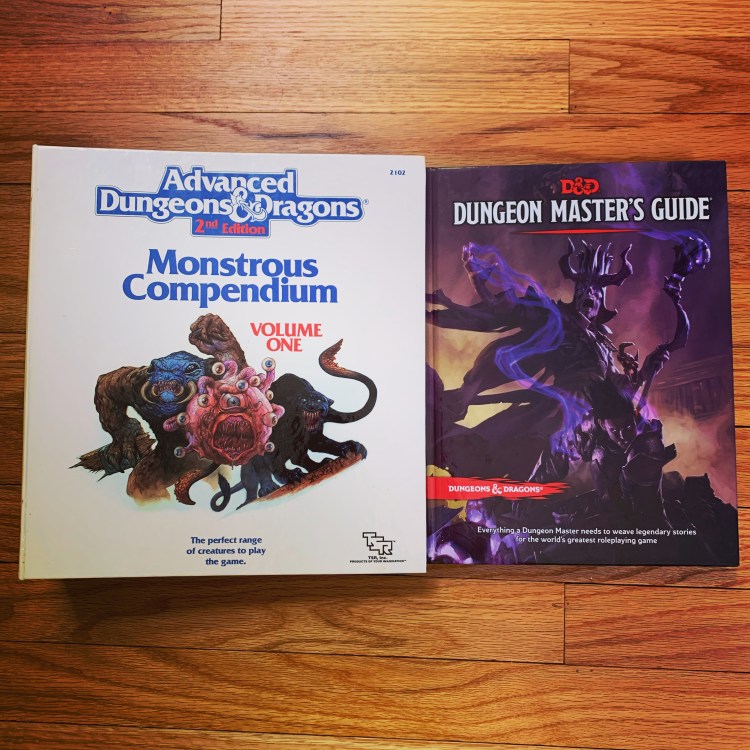

Ramadan 24

Here is something old and something new: Advanced Dungeons and Dragons, 2nd Edition “Monstrous Compendium: Volume One” and the more recent 5th edition “D&D Dungeon Master’s Guide.” Dungeons and Dragons, which started the table-top role-playing phenomenon, was a game superbly suited to foster my imaginative world-building. I was likely introduced to it in the mid-80s through the “Endless Quest” books that D&D published in answer to the popular “Choose Your Own Adventure” series. I’m sharing the Monstrous Compendium because it was a gift from my grandmother, from my father’s side. Although she spoke no English (and I barely understood Vietnamese) she asked me at the mall what I would like and I picked this. I’ve no idea what she made of the cover (c’mon look at it), but she bought it nonetheless saying something like, oh, it must be good for school (education, after all, was everything). While it may not have directly served that purpose, it certainly fed my imagination. Truth be told, I never actually played a proper session of D&D. As a young boy, I didn’t know which books I needed, let alone afford at the time. Instead I ended up with a hodge-podge of books spread across different editions and rulesets, which just didn’t work together. So instead, I made up my own pen and paper role-playing game. I still have the binders filled with loose-leaf pages of notes and charts. In fact, in 5th grade, I remember getting 13 of us together to play an epic session of my game. It was glorious, though my most vivid memory of that day was fruit punch spilled on a do-not-spill-anything-on-this-carpet carpet. That all came to a halt, however, when my unknowing refugee parents succumbed to the Satanic panic of the late 80s thanks to the wily whisperings of some Evangelical friends. In recent years, there’s been a cultural sea change. As more people seek to escape social media with actual face-to-face social interaction, D&D has become mainstream with the series, to its credit, become much more diverse and inclusive than its earlier incarnations. And honestly, what game offers this degree of creativity, collaboration, communication, and critical thinking all in one? And yes, I have 5th edition because I’m still game… Ramadan 24

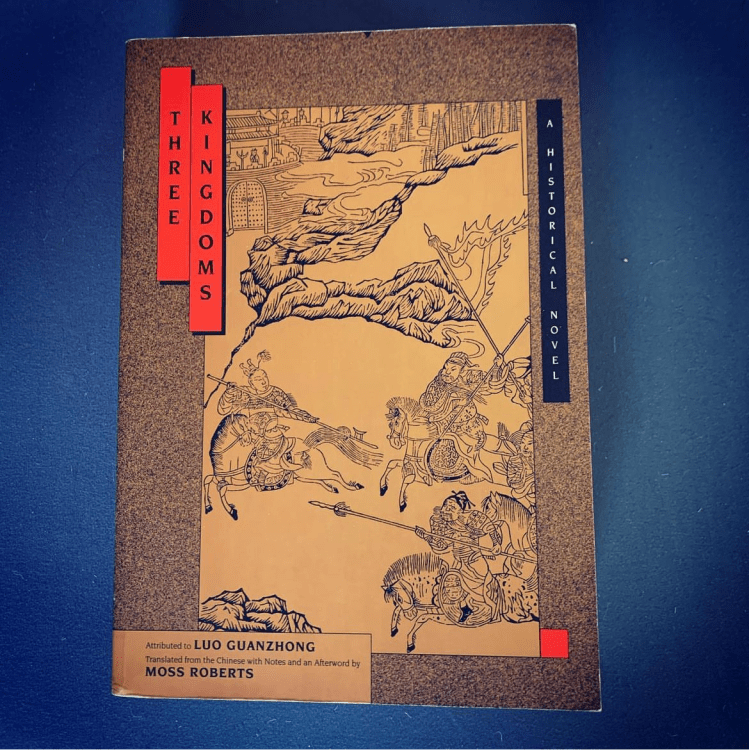

Ramadan 25

This book of 1096 pages is Moss Roberts’ translation of the Ming dynasty classic “Romance of the Three Kingdoms” by Luo Guanzhong (d. ca. 1360-1400). As a child I discovered this literary work through a weekend video game rental, “Destiny of an Emperor” for the Nintendo. The game was set in China at the fall of the Han Dynasty when imperial unity dissolved into a period of three warring kingdoms: Wu, Wei, and Shu (220-280 CE). While the game regaled me with a plethora of heroes and villains (enough to give George R.R. Martin a run for his money) with exploits and bravado to match, it also traced out a generation-spanning saga of immense scale. I found other games based on the same story, which lead to my realization that this was all based on an actual period of history, though romanticized. Luo’s literary rendition offered me a sense of meaningfulness that the tales of King Arthur and Robin Hood never did, as engrossing as they were. I simply could not see myself in those stories, where here I could. It was not until high school, however, that I was able to access a good English-language translation, this one, at a local university library (Virginia Commonwealth University). At last, I could finally read for myself the tales that I had up until then only experienced through video games. It was also in Roberts’ translation that I fell in love with annotations. I read his copious and detailed endnotes with relish in order to deepen my understanding of those stories. In fact, my early fascination with this historical period eventually led me to my undergraduate major in history (I doubled of course) where I studied the Cultural Revolution. And it was maybe half a decade later that I learned from my father that he too had been raised on these same stories! The saga of the “Three Kingdoms” had been so significant for each of us without the other realizing it. Moreover, I had had no idea how extensive the cultural hold of this epic has been in East Asia until that time. Such was my isolated upbringing in central Virginia. Through “Three Kingdoms: A Historical Novel” my world managed to become a bit larger. Ramadan 25

Ramadan 26-1

Many years ago, I carried these three volumes back with me from Jordan, I believe. I recall it was quite the find the time because I had just resolved to make the Qur’an commentary of Abu al-Qasim al-Qushayri (d. 465/1072), his Lata’if al-isharat (“The Subtleties of the Signs”), the subject of my dissertation and this was the edition produced by Ibrahim Basyuni. I had learned by then that Basyuni’s edition was the only real edition worth consulting and I was looking for my own print copy to work with rather than the library’s or a digital one. All the other editions that I had checked were nothing more than blatant copies of Basyuni’s work, all of which failed to acknowledge that unsurprisingly. Still, Basyuni’s edition is far from ideal since it is based on only two partial and problematic manuscripts. Of course, I eventually obtained and made use of far better manuscripts, but having a print copy in front of me still proved helpful. I ended up using these three volumes quite a bit for nearly a decade until the book finally appeared. While I have not checked recently (since I’ve moved on from Qushayri), I don’t believe a new edition of the Lata’if has ever been prepared. Still, I owe quite a bit to Basyuni for being the first to edit the commentary along with several other important works by Qushayri. Ramadan 26, the first

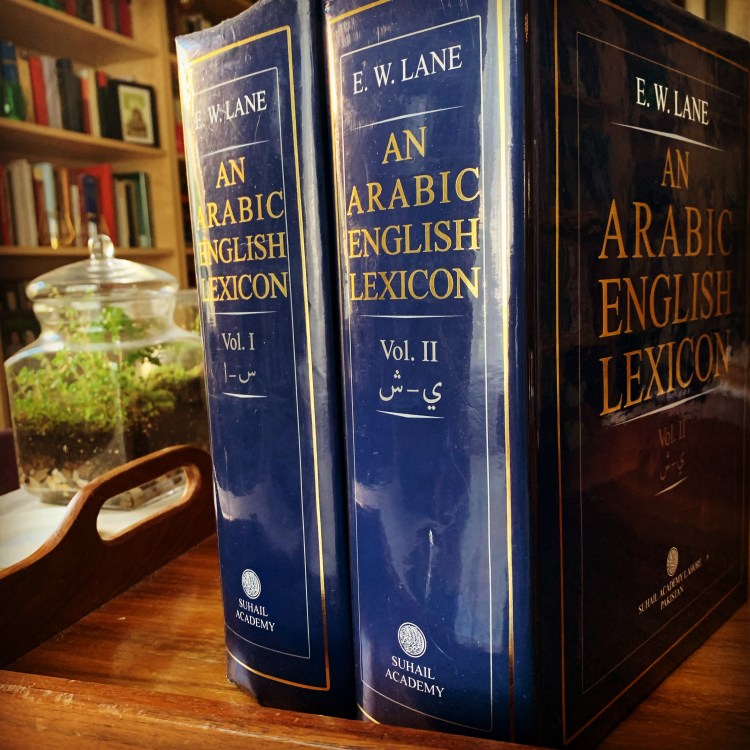

Ramadan 26-2

I debated whether I should include a dictionary in this list, but then I thought why not? Dictionaries are great! In fact, a better reason came to mind than simply the lexical utility that a dictionary delivers. This immense two-volume edition of Edward William Lane’s (d. 1876) “An Arabic English Lexicon” has proven a helpful resource in teasing out obscurantia and discovering other registers of meaning, even if I do not make all that frequent use of the work. And as I hope the picture conveys, this set is a true behemoth. Many muscles are strained when it beckons. With every move from house to house, with every bitter decision to shuttle it from office and home and back again, I am reminded of how it came into my possession. It was through the very generous efforts – and likely great sacrifice (just look at the size of it!) – of a good friend that this weighty pair of tomes first journeyed from Pakistan to Boston where I gratefully received it. So, on top of its conventional uses, it serves as a ponderous reminder that we never get to where we are alone, that I am always indebted to my friends who have joined and helped me at different points along the way. Thank you Shoaib Ghias for the of Lane. Ramadan 26, the second

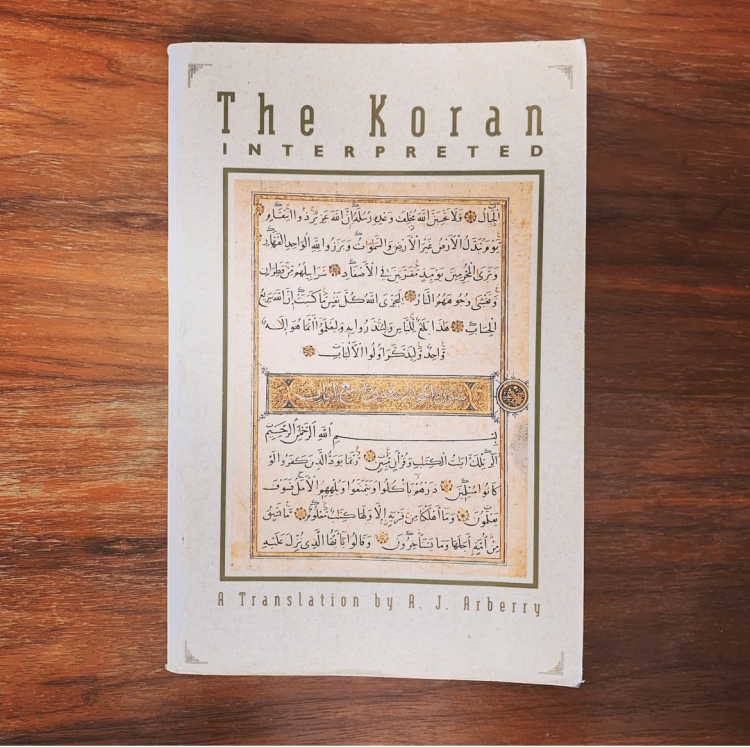

Ramadan 27

On this particular day of Ramadan I thought it would be appropriate to share something related to the descent of revelation. Here is the first translation of the Qur’an that I ever owned, “The Koran Interpreted,” translated by A.J. Arberry (d. 1969). As a Second Year in college, I purchased it from the University of Virginia bookstorewhen Prof. Abdulaziz Sachedina assigned it for his course “Islam in the Classical Age,” which was a class that I took on a whim. It would also be my first class on Islam as well as my first proper exposure to the faith. I have found that Arberry’s translation manages to fold into its English rendition a bit of the ambiguity that is present in the language of the Qur’an, something a friend pointed out to me several years later, which is one of the reasons I continue to appreciate it. There have been many translations that have appeared since, of course, each seeking to do something different. I’ll note that some readers of Arberry’s translation have found it hard to use, simply because the numbering of the verses does not follow that established by the 1923 Arabic edition of the Qur’an prepared by al-Azhar University. Instead, the verse numeration in Arberry’s translation follows the earlier 1834 Arabic edition of the Qur’an prepared by Gustav Flügel (d. 1870), which for a long while was the preference of Orientalists. In any event, “The Koran Interpreted” remains with me because of the door it so critically helped to open those many years ago. Ramadan 27

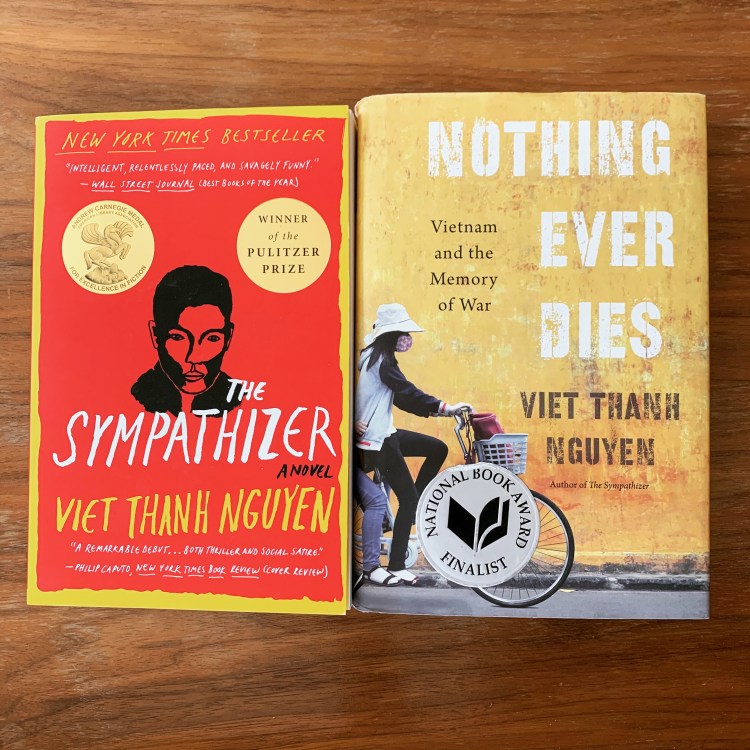

Ramadan 28-1

A few years ago, I first encounter Viet Nguyen’s work when his novel “The Sympathizer” was gifted to me by an appreciative auditor at the end of my Islamic Theology class. When I received it, I had never heard of the author or the novel before and was a bit puzzled by the choice (I guess we share a last name?). I let the book sit unread for far too long, not realizing how good a read it would be – though the Pulitzer should have been a pretty big clue. When I read it at last, I enjoyed the story greatly even with its rare spotty part (for example, the film consultancy bit seemed much too contrived to me) because the author writes with some of the most memorable turns of phrases I’ve come across of late. As wordcraft goes, the book is an absolute pleasure to read. And thanks to his novel, I then discovered Nguyen’s scholarly work, this book in particular, “Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War.” While the work focuses on Vietnam and the wars fought there, Nguyen delivers the same linguistic musicality found in his first novel to his incisive insights and findings on acts of memory and forgetting, storytelling, power, and war in general. It’s relevance stretches far beyond that specific historical horizon. While I’ve never met Viet Nguyen, I’m looking forward to the words that he’ll pen next. Ramadan 28, the first

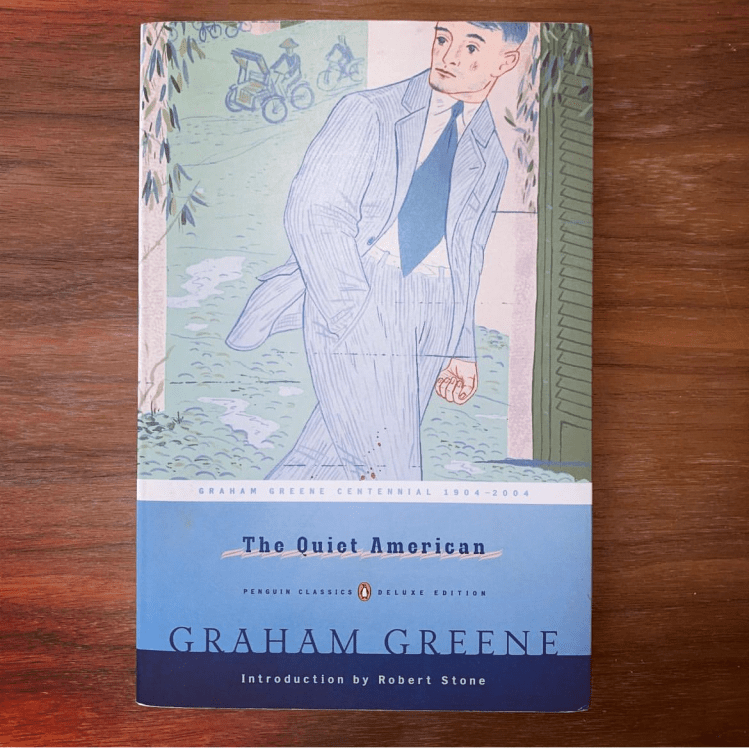

Ramadan 28-2

Because Vietnam is on my mind with the last post, I felt it appropriate to share another writer whose work has touched upon it that I also enjoy. I am referring, of course, to Graham Greene (d. 1991) and his novel “The Quiet American.” It is an exceedingly well-written and thoughtful work, that offers a pretty sharp critique in the story of the figurative U.S. during that time. The story was a favorite of Anthony Bourdain’s, who, as a chef and traveler, held a special fondness for Vietnam. I even remember him opening one of his episodes on Vietnam with a brief, but reverential discussion of this book. If you are in search of a good read, nearly any of Greene’s novels will do, but if you haven’t read “The Quiet American” yet it is an excellent place to start. His books are a continual pleasure to read with each bringing its own distinctive and memorable weight to them. Ramadan 28, the second

Ramadan 29

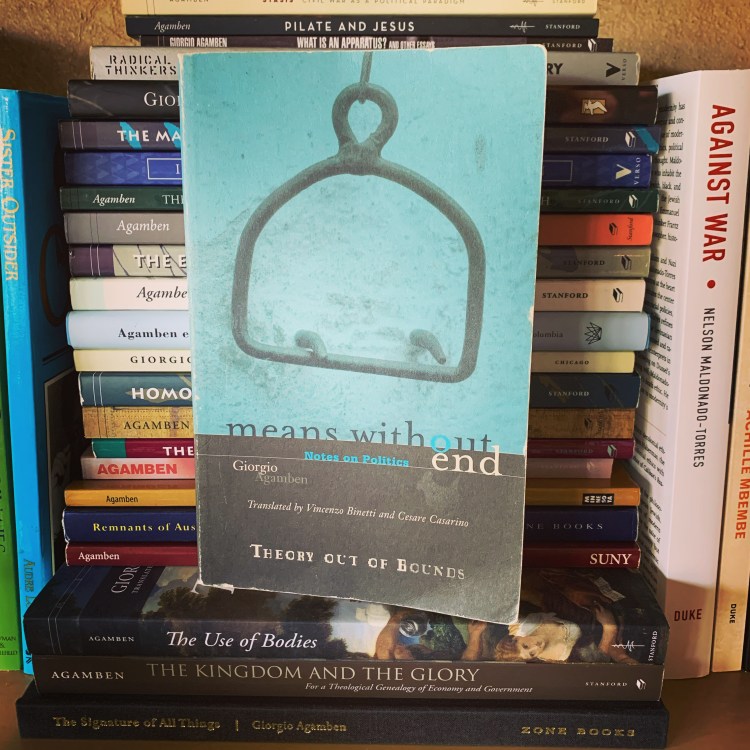

Of contemporary thinkers of note that I have more recently come to appreciate, I would count the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben highly amongst them. His gaining popularity in the Anglophone world can be attested by the increasing number of English translations being published as well as the many references to be found in recently published works. Much to his credit, Agamben has introduced a bevy of key concepts that have proven significant for critical scholarship these days. But like Fred Moten, Agamben’s writing can dense and challenging at times. The time that I invest in reading him, however, typically seems to be worth the effort. As can be spied in the background, Agamben has been prolific and I hope to share more of these titles in the future. Today, I am featuring the text that served as my introduction to him. “Means without Ends: Notes on Politics” is a set of essays gathered into a slim volume. Because of its brevity, the ideas herein, concerning matters like refugees and biopolitics, offer only a brief glimpse into his broader world of thought. Nevertheless, this work continues to serve as a productive provocation for my present undertaking and proved, upon my first encounter with it, to be the start of a much longer intellectual engagement. Ramadan 29

Ramadan 30

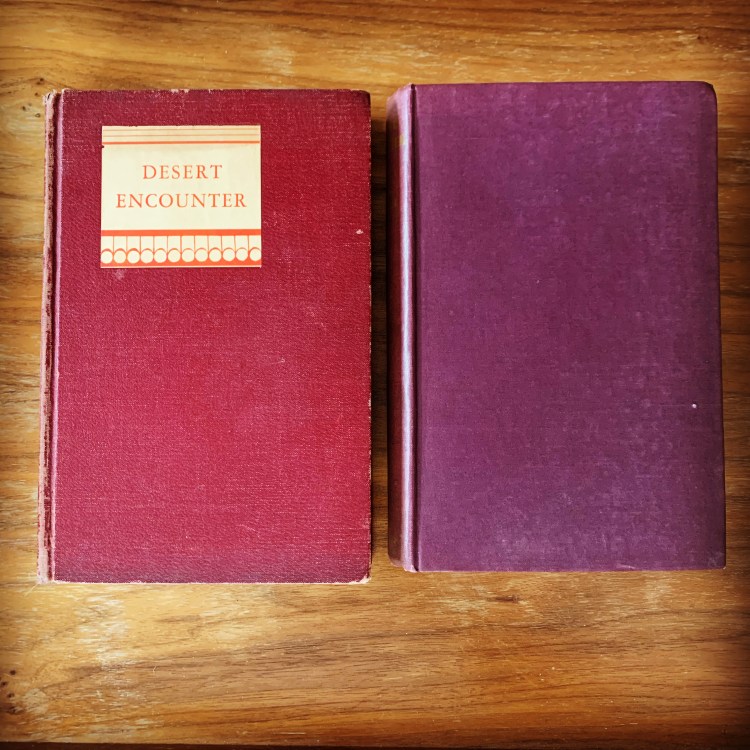

Today is my birthday, but it just so happens that today is also the day I staged an elaborate proposal to Kiran Tahir so many years ago, which itself is a story for another day. For now I’ll simply say that it took her on a wending journey – a hunt really – through Cambridge with a guide sworn to silence and involved (in no particular order) donuts, enigmatically composed magnetic word poetry, help from many dear friends, the Harvard musalla, and the Gibb Reading Room in Widener library – named after the Islamic studies scholar H.A.R. Gibb (d. 1971). It was a journey much like that taken and so captivatingly written about by Danish convert to Islam Knud Holmboe (d. 1931) as he journeyed across North Africa in a Chevrolet that had seen better days. Holmboe vividly captures in “Desert Encounter: An Adventurous Journey Through Italian Africa” his experiences during his trek from Morocco to Libya, while documenting the egregious colonial abuses that he witnessed along the way, especially those perpetrated by the Italian colonial regime. In fact, the title of “Desert Encounter” in the original Danish is “Ørkenen Brænder” or “The Desert is on Fire.” By now, dear readers, you’ve realized that the scavenger hunt proposal was probably nothing like Holmboe’s sojourn, though I’m sure both journeys were quite memorable for the parties involved. The real reason I’m sharing Knud Holmboe’s “Desert Encounter” today is because this was one of the first books that Kiran and I bonded over. She had mentioned it was one of her favorite books so naturally I took a keen interest and read this very copy on the left that she lent to me. It remains a powerful story that still holds up today, as anti-colonial literature is wont to do. Find it and read it! Kiran’s copy on the left is the first U.S. edition published in 1937. On the right is the first British edition from 1936. We found this second one (sometime after getting married) while on one of our many used book tours, just the sort of outing that is sorely missed these days. Happy proposal-versary Kiran! Happy birthday to me, ahem. And wishing a blessed last day of Ramadan for those observing. One more to come isA. Ramadan 30

Eid

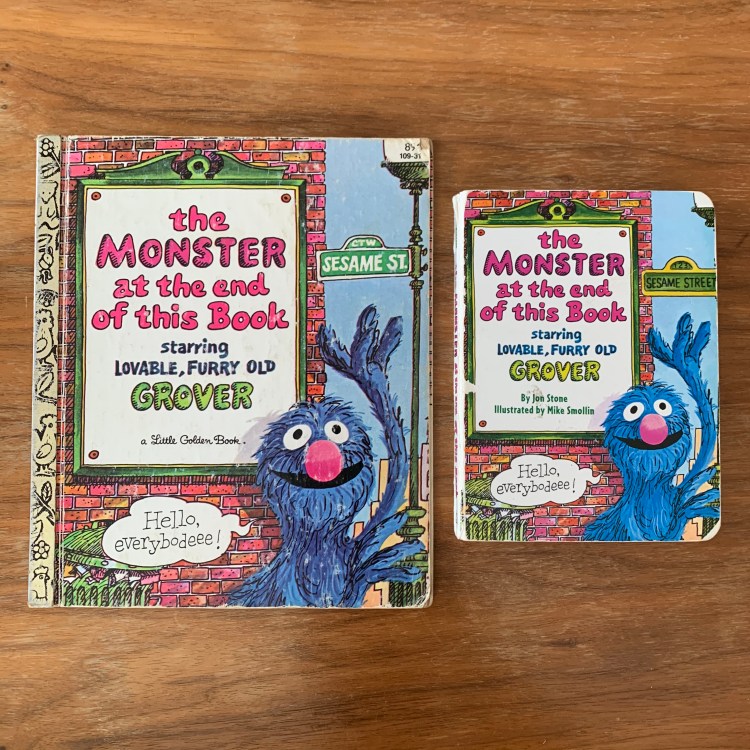

Eid Mubarak to all! On this day of celebration, with Ramadan having drawn to a close, I wanted to share with you a book that digs deeply into my past. Of all the books that I’ve shared, none goes as far back in my life as this one: “The Monster at the End of This Book” starring lovable, furry old Grover (as indicated), written by Jon Stone, and illustrated by Mike Smollin. This unassuming work is one of my most favorite books from my childhood. How can such a humble tome do so much thought-provoking and heart-quaking work? Smollin’s art is exquisite, from the fine line drawing to the superbly matched coloration. Each page conveys remarkable movement and immovability at the same time. Grover himself – no amateur to the written page – delivers a memorable, fourth-wall breaking performance, which for me was a minor revolution back then — Grover is speaking to me! And thanks to Stone’s expertise in the craft, the plot takes a most unexpected turn, reminiscent of other mindbenders like the Christopher Nolan’s film “Memento” or Alan Moore’s graphic novel “V for Vendetta.” Of course, I dare not spoil the plot for you, but rest assured, this is a work of genius. My little mind was blown away when I first read it and I feel strongly that its imaginativeness had much to do with making me the person who I am today. And even when I reread it now, with my daughter Maryam, I still find myself picking up the pieces of my shattered mind to slowly piece it back together in the quietness that abides after. I have two editions of this book as well (of course!). On the left is my original copy, a 22nd printing from 1982 in the famous Little Golden Book series. It was so well loved that the back cover has become detached. On the right is a 1999 Random House board book copy that we bought used for Maryam when she was still of the most wee stature. Whatever your age, seek this book out and behold its wonders! Eid al-Fitr 1441/2020

Post Script

Although Ramadan is over and Eid will soon draw to a close, I would like to say that this is not the end. I’ve found writing these daily posts quite a satisfying undertaking and a good exercise in writing and reflection. I plan to continue them for some time, though at a much less frantic pace. I’ll aim to post weekly or so because, after looking at my shelves, I’ve realized I have many more books – and many more reflections – I’d like to share.

1 June 2020

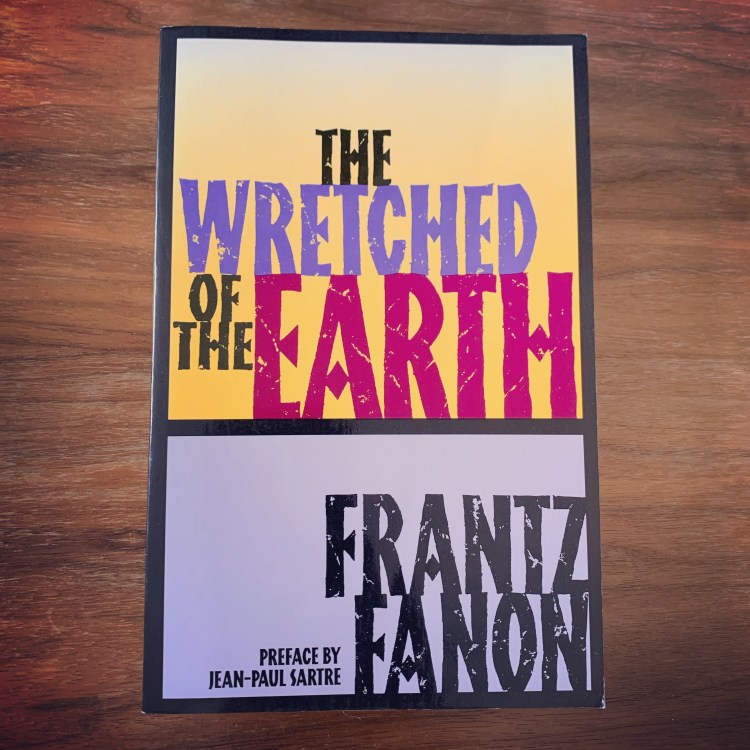

In the wake of the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor (amongst continuing and countless others) at the hands of the police, #BlackLivesMatter has irrupted through the haze of the COVID-19 pandemic with renewed urgency. It seems appropriate, at least to me, to share the work of the revolutionary writer and psychiatrist from Martinique, Frantz Fanon (d. 1961) and his seminal work “The Wretched of the Earth.” I had debated included him during Ramadan, but resolved to leave him for later once I had decided to continue sharing books afterwards. I did not realize that I would feel compelled to share him so soon. While addressing the plight of the colonized and the question of violence from the vantage of the Algerian National Liberation Front in their struggle for independence from French colonial forces, I, like many others, see his project as being far more wide-reaching and entangling than that specific context. In fact, I cannot help but see the situation in the United States as a pernicious form of domestic colonialism where many of the points raised by Fanon in this book continue to have some bearing, even if taken only as a series of provocations. There is, of course, more to Fanon’s thought than “The Wretched of the Earth,” but I share this work now because it was where my encounter with Fanon first began. Let us end with some words from Fanon himself, words that indeed sought to connect one particular struggle with the struggle of many others worldwide: “A colonized people is not alone. In spite of all that colonialism can do, its frontiers remain open to new ideas and echoes from the world outside” (p. 70). 1 June 2020

11 June 2020

“White Christian Privilege: The Illusion of Religious Equality in America” by Khyati Y. Joshi is a book for which I’ve been eagerly waiting. Words do not convey how ecstatic I am to have this in my hands at last. For the past few weeks I’ve been thinking and planning for the unknown fall semester. Preparing as best I could, I also began to think about what I would teach in the spring, namely my “Islam, Race, and Power” course, though with significant updates and revisions. To that end, I looked up the status of this book just last week. Khyati mentioned her commitment to writing this project to me a few years ago and, thanks to my running into her again at this past AAR conference, I learned that the book’s arrival was imminent. Finding the publisher (NYU Press), I expressing interest in the book for course adoption and joined the queue for its release, though I expected delays given the ongoing pandemic. I was surprised to receive it so soon just yesterday. While I plan to use it for the spring, I also knew that this work would have direct relevance for my present research. Unsurprisingly, I spent last night reading the introduction and the beginnings of the first chapter. From what I’ve read, it is brilliant. With accessible expertise, those first pages lay forth the central concepts to be critically undertaken in the chapters to follow: Christian privilege, Christian normativity, and Christian hegemony as they relate to White Christian supremacy in the United States. It feels inaccurate to say the book is “timely,” if only for the simple reason that the structural inequalities that the author addresses have long been with us. Nonetheless, given this moment when systemic racism is garnering the energy and attention it has long deserved, this work also brings into relief the religious dimensions at work – dimensions that are too often dismissed, overlooked, or obfuscated. I am grateful for the conversations that this book initiates. 11 June 2020

19 June 2020

A recent arrival, I have to admit that I have yet to properly begin this book. Nevertheless, Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr.’s “Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party” seemed a fitting work to share on this day. My interest in the Black Panther Party originally stems from the group’s formation from out of Malcolm X’s radical vision and legacy. But of course, there is also the matter of the organization’s abiding relevance. The struggles of the Black Panther Party during its time are no less pressing now as they were then. There are both conceptual and organizational questions worth asking in our present that this history might better inform. Although the volume is substantial (it’s fairly daunting in size), I’m looking forward to what it documents within. For the time being, I will defer to the judgement of Angela Davis whose praise stands out on the back of the book: “Because they do not shy away from the contradictions that animated this movement, Joshua Bloom and Waldo Martin pose crucial questions about the genesis, rise, and decline of the BPP that are as relevant to young generations of activists as they are to those who came of age during that era.” 19 June 2020