Following up on first run, I decided to continue the practice of sharing a book day during Ramadan. Most of the works shared here were ones that I was actively consulting in writing my second theology book on Islam, race, and the displaced, which remains in progress. More significantly, however, is that the booklist also mentions and honors Sohaib Sultan, who passed away during this time. Back to the MRB.

Ramadan 1

Every day of last Ramadan, I shared a book or so that had some degree of significance to my personal formation. I would like to continue that practice of book-sharing this Ramadan as well. The thematic focus, however, will be slightly different. Since writing “Modern Muslim Theology,” I have been dedicating myself to writing its theological successor, a work whose title continues to change. What I can say is that it concerns prophets and strangers, systemic evil, modern structural racism, and mass displacement, among other matters. Since I am in the thick of this undertaking as we speak (isA, roughly halfway through?), I thought it apt to share the different works with which I’ve been engaging and wrestling in the process of bringing this book to life (I will also endeavor not to repeat books mentioned last year). With that said, a central theme within this works concerns the Islamic discourse on the gharīb and the ghurabāʾ, strangeness and strangers. While the hadiths to this effect constitute a central axis of reflection, I have also found this book immensely insightful as well. This is “The Book of Strangers: Medieval Arabic Graffiti on the Theme of Nostalgia” translated from the Arabic by Patricia Crone and Shmuel Moreh. While traditionally ascribed to Abū’l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī, the translators compelling cast doubt on the attribution, speculating instead that the unidentified author was likely a resident of Baghdad writing around 380 AH. Moreover, the work has been known by several names: Kitāb adab al-ghurabāʾ, Udabāʾ al-ghurabāʾ, and simply Kitāb al-ghurabāʾ. Capturing, most often anonymously, the musings of literate Muslims on the plight, perils, and pleasures of strangerhood, I have found the work an important touchstone in my own reflections on the religious import of estrangement and the mantle of the stranger.

Ramadan 2

The contemporary literature on strangers, while interesting in its array, has been of fairly limited relevance to my work here. One book, however, has proved an incredibly helpful conversation partner, Sara Ahmed’s “Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality.” The work marks one of Ahmed’s earlier monographs, though that fact makes it no less significant or incisive. Her treatment of strangers is capacious and challenging. She questions notions of home, belonging, and nation as she unfolds her ethical vision and embodied experience of the stranger. While our respective readings of strangers do not always align and are even sometimes at odds (our ends are quite different), I appreciated, nonetheless, how Ahmed takes the stranger – in body and mind – as a source for an alternative community. I am trying to develop a similar idea through a theologically framing of the gharīb.

“Strangers are not simply those who are not known in this dwelling, but those who are, in their very proximity, already recognized as not belonging, as being out of place.” (21)

“The projection of danger onto the figure of the stranger allows violence to be figured as exceptional and extraordinary – as coming from outside the protective walls of the home, family, community or nation. As a result, the discourse of stranger involves a refusal to recognise how violence is structured by, and legitimated through, the formation of home and community as such.” (36)

“The distinction between native and stranger within a nation is not simply enforced at the border: rather, that distinction determines different ways in which subjects inhabit – which involves both dwelling and movement – the space of the nation.” (101)

Ramadan 3

Sometime after “Modern Muslim Theology” was published I began to hear from divinity students that my style of writing reminded them of that of Willie Jennings, especially as it appears in his “The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race.” I found those comments fairly intriguing, but I had to admit I had not yet read his book, even though it had been suggested to me earlier given its subject matter. As we all know, the pile of books we hope to read never shrinks and only grows. Then, when I was describing what I was working on next to a friend and colleague, she told me that I should meet with Jennings given our similarities and proximity to one another. But the pandemic hit, so I have yet to reach out. Nevertheless, I spent a worthwhile part of my isolation time reading and relishing this book. It is brilliant. I regret not reading it sooner. In fact, I am sure that had I read this before last Ramadan I would have included it then in my list of formative books given how compelling, enduring, and provocative its ideas have been for me. The book surfaces a specific trajectory of Christian theology that became central to colonial expansion and the capitalist exchange of goods. Despite the heretical nature of this theology, it prevailed and predominated resulting in enduring tectonic changes for us all. After having passed through the alchemical crucible of colonialism, animated by theological catalysts, our relationship to space and our own bodies has been radically reconfigured.

Allow me to share a passage that Jennings writes after he presents the account of a slave auction in Lagos on August 8, 1444. The stylized eyewitness account is written by Gomes Eanes de Zurara, the royal chronicler to Prince Henry of Portugal, who was also present at this early morning auction. Jennings’s analysis reads: “The christological pattern of his narrative illumines the cosmic horror of this moment and also helps the reader recognize the unfolding of a catastrophic theological tragedy. Long before one would give this event a sterile, lifeless label such as ‘one of the beginning moments of the Atlantic slave trade,’ something more urgent and more life altering is taking place in the Christian world, namely, the auctioning of bodies without regard to any form of human connection. This act is carried out inside Christian society, as part of the communitas fidelium. This auction will draw ritual power from Christianity itself while mangling the narratives it evokes, establishing a distorted pattern of displacement. Christianity will assimilate this pattern of displacement. Not just slave bodies, but displaced slave bodies, will come to represent a natural state.” (22)

When I write about the many human disfigurations of creation, I do so with passages like this deeply etched into my mind.

Ramadan 4

There is much to philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt’s (d. 1975) extensive body of work, though I have not engaged with it as extensively as I would have liked. Born in Germany into a Jewish family, she was forced to flee the country as a young scholar shortly after the rise of Hitler and Nazi Germany in 1933. Eventually she would settle in New York in 1941 where she would spend the rest of her days. Once there, she would go on to write about a number of important subjects, foremost of which concerned power and the nature of evil, appropriate and unsurprising given the times and her life experiences. The work that I am sharing here, however, “The Human Condition,” first published in 1958, is a more abstract philosophical exploration of what she calls vita activa (“the active life”) in contrast to and distinction from vita comtemplativa (“the contemplative life”). I have been working through it in order to better understand her conception of praxis, especially as it relates to speech, given how a substantial part of my present work-in-progress is framed as an examination of faith and praxis in response to the systemic evils we face today. Of course, given my similar concern for evil and its engrained structures I am sure I will be revisiting Arendt soon enough.

Ramadan 5

This is not the book I had intended to share this morning, though I had fully intended to share it sometime this month. Nor is this book directly related to my current project, but it is the inspiration for what I feel compelled to work on next. I share it now because yesterday, around maghrib, my friend Sohaib Sultan passed away after a year-long trial with cancer. The moment of his death was written. God has called for his return. Sohaib’s terminal diagnosis one year prior, however, was not a cause for despair. Rather, he turned it into a source of blessing with his characteristic patience and care. With what time was left to him, Sohaib worked to come to terms with his mortality. He learned to live with dying. He learned to do so faithfully, or so I strongly believe. In that all too short span, Sohaib seemed to be able to find acceptance, contentment, and then happiness with his imminent demise – a beautiful process of realization that our mutual friend Omer Bajwa shared with many of us just hours before Sohaib’s final moments. More than this, however, Sohaib spent this past year trying to prepare the rest of us – the many beloveds he has leave behind – for his eventual departure from this life and our lives. He did so with the utmost compassion, love, and light. He seemed called to this task out of his deep faith and genuine commitment to pastoral concern. Up until his final days, he sought to make this very moment – this difficult time of grief and mourning that we are in now – as easy as possible for the many he leaves behind. Sohaib was a rare soul and dear, dear friend. I miss him immensely.

Even though he was the one dying, his call to bring comfort to the rest of us is telling. Death, a fate that we all share, has become an exceedingly hard reality for us to face in our times. Many of us no longer know what to do with it, how to live with it, or how to prepare for it. In fact, at least for my family, death seems to have a strong hold over this unfolding year. Back in early February, Kiran lost her father to the ravages of COVID-19. After we laid him to rest, I spent many days dwelling on death. Soon enough, I turned to a book that Kiran recommended, one which she had read in the years prior to her father’s demise, Atul Gawande’s “Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End.” It had proved important to her then and it has proved its importance to me now. Of all the books that I have read this past year, and they are many, I consider this one the most significant one that I have read, even though it is unconcerned with religion or theology. Instead, it is fully concerned with how we die, that unmovable reality that we all too often try to avoid in thought and action. But in this book’s pages, Gawande, a medical doctor, does much to reveal the structural problems that obfuscate our understanding of death and trouble how we die. It is a book that addresses at a most practical level – the level of medicine and medical care – how we choose to live our last days. If there is a book you ought to read, it is this one – not only because we all must die at some point, but because we will likely have to oversee, before that moment, the passing of our loved ones (parents and partners) in their infirmity and old age, whether we choose to recognize it now or not.I write this out of love. I write this in remembrance of Sohaib Sultan and Mohammed Jawad Tahir. Inna li-llahi wa inna ilayhi raji’un. Truly do we belong to God and to Him shall we return. May God grant them both Jannat al-firdaws.

Ramadan 6

Today’s post was originally intended to be my follow up to Arendt’s “The Human Condition.” This is the classic work “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” by the Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire (d. 1997). I’m sharing it after Arendt due to Freire’s equally interesting engagement with praxis, which he defines as “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it” (36). Working alongside farmers and laborers he witnessed the empowerment that came with literacy. I have also turned to him for his general, but incisive analysis of structural oppression, dehumanization, and his notion of conscientização (conscientization) that swells forth in response. Freire’s thought has been deeply influential across numerous communities. For instance, Black Consciousness activist Steve Biko (d. 1977) and Catholic educator Anne Hope (d. 2015) worked to bring Freire’s method to fruition in the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. In a similar spirit, Augusto Boal (d. 2009), while in exile in Argentina and Peru, drew on Freire’s pedagogy to develop the theatrical method of Theatre of the Oppressed. Here is a line I found particularly compelling as I write on structural oppression: “To surmount the situation of oppression, men must first critically recognize its causes, so that through transforming action they can create a new situation, one which makes possible the pursuit of a fuller humanity. But the struggle to be more fully human has already begun in the authentic struggle to transform the situation” (32-33).

Ramadan 7

Several years ago, when I visited the Twin Cities, my friend Maheen Zaman took me to Daybreak Press Global Bookshop where I was able to peruse an admirably curated collection of books. It was back then that I really learned about Daybreak, the present book’s publisher. Before I discuss the press further, first let me say a few words on the book and its relevance.

Narratives and stories play a central role in my present project. It should be no surprise, then, that I would draw upon particular episodes from the life of the Prophet Muhammad. I have consulted, of course, many of the usual suspects with respect to the sources, both classics of the sīra genre (or the biographical literature on the Prophet) as well as more contemporary accounts and renditions. The present book, which arrived just before Ramadan, is a sizeable 2-volume collection that falls into the latter category. Entitled “A Compendium of the Sources on the Prophetic Narrative: Abridged” its author, Samīra bt. Ḥusnī al-Zāyid, originally published “Mukhtaṣar al-Jāmiʿ fī al-Sīra Nabawiyya” in six-volumes in 1992. A team of three translators, Susan Imady, Tamara Gray, and Randa Mardini, worked with the author over seven years to bring her meticulously written book into English. When I first learned of its existence, I was keen on eventually obtaining it, not only because of its contents, but also because the persons involved were all women. In fact, this translation was produced by Daybreak Press, the publishing division of Rabata, a religious, woman-focused educational organization founded by scholar and educator Tamara Gray. According to the organization’s mission statement “we work to build a better society through the educational and spiritual development of women by women, amplifying the female voice in scholarship and publishing, and graduating teachers and religious leaders ready to serve their communities.” While physically based in Minneapolis, Rabata has a global reach. While I have yet to read beyond its initial prefatory pages, I’ll be reading more carefully soon those sections relevant to the narratives that I’m lifting up in my own work.

Ramadan 8

Part of my next work is focused on discussing colonialism’s intersection with several modern forms of structural oppression. To that end I’ve been immersed in the writings of several Latin American and Caribbean scholars like Anibal Quijano (d. 2018), Sylvia Wynter, Walter Mignolo, and Nelson Maldonado-Torres who offer exceptionally critical looks at the machinery underlying colonialism in the Americas and its after effects, especially “coloniality.” However, I’ve been working with a parallel account of Africa as well, another well-known classic “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa” by the Guyanese Marxist historian Walter Rodney (d. 1980, assassinated). First published in 1972, the book is a sweeping history of the continent that compellingly delivers an extensive indictment of capitalism and European colonialism.As some of you might be aware, I’ve also been working to incorporate Vietnam into my next work on Muslim theology and I’ve shared some of those pieces in the past. While the move might seem incongruous, I believe it works quite well (we’ll see isA). After all, the struggle in Vietnam, like the Algerian Revolution, was a central occupation for liberation struggles worldwide. I was pleased, then, to find Rodney making his own connections to Vietnam in the course of his own sharp analysis. Writing with the war in Vietnam still raging, he writes: “In recent times, it has become an object of concern to some liberals that the United States is capable of war crimes of the order of My Lai in Vietnam. But the fact of the matter is that the My Lais began with the enslavement of Africans and American Indians. Racism, violence, and brutality were the concomitants of the capitalist system when it extended itself abroad in the early centuries of international trade” (105). If you are unfamiliar with My Lai, seek to rectify that.

Ramadan 9

In 2017, on this precise day of Ramadan, the ninth day of the Islamic month, Grenfell Tower in West London was consumed by flames. The crackle of this fire was heard around the world. We watched transfixed in horror as it burned. Our grief (and anger) grew as the stories of the lives lost mounted. It was a tragedy that demanded witness. It was a tragedy perpetrated and facilitated by many different interlocking policies, institutions, and systems of supremacy and marginalization, locally and most assuredly more broadly. As time went on, I continued to look back to Grenfell trying to apprehend the machinery that set the terrible blaze. I did not want – I do not want – its memory to fade. When I learned of “After Grenfell: Violence, Resistance and Response,” edited by Dan Bulley, Jenny Edkins and Nadine El-Enany, I knew right away that I needed to delve into its contents. The book is a reflective collection of critiques, memorials, and artistry. It has helped to better understand what transpired at Grenfell and it has apprised me of the efforts and energy that have emerged in its aftermath.

Two years ago, I shared this piece on FB:

https://www.facebook.com/alakhira/posts/10107388656904131

Two years ago, I shared a piece here on FB on Grenfell that started as the kernel of an idea. I have since revised and expanded it in order to open one of my chapters, in fact the first one I completed, Chapter Two tentatively entitled “The House of Pharaoh and Systemic Evil.” I share its current state now with all citational references removed given the limitations of this platform. My apologies to those who read that initial draft, as it may ring overly familiar.

Ramadan 10

I share today two books because of how one fortuitously led me to the other. On the left is a book of poetry, Sonia Sanchez’s “A Blues Book for Blue Black Magical Women.” A noted poet and and writer, Sanchez has published a celebrated array of poetry, plays, and other works over the course of her ongoing career. I became interested in this particular collection, however, thanks to the important work done by Silvia Chan-Malik in “Being Muslim: A Cultural History of Women of Color in American Islam.” This work is itself important for the critical attention it draws to the lives of Muslim women and how those lives are framed and analyzed. It was during its introductory pages that I learned that Sanchez had converted to Islam in 1972 through the Nation of Islam and remained so until 1975. It was during this period in her life that the poems of this slim, blue volume were composed and published. Tellingly, five familiar verses of the Qur’an precede her poems, the first lines of revelation received by the Prophet Muhammad (Q. 96:1-5). Let me share the following verses from the penultimate poem in the collection:

WE ARE MUSLIM WOMEN

dwelling in His hour

guardians of the gate of Islam

recorders of tomorrow

an adoration.

WE ARE MUSLIM WOMEN

moving in the ark of time

women of a million years

passing thru the door of the world… (58)

Ramadan 11

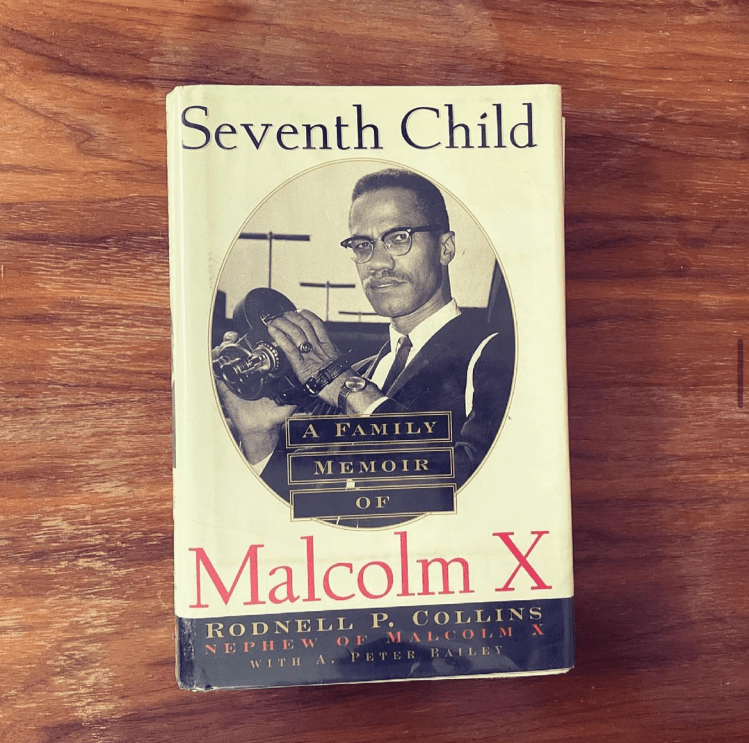

These last few years, numerous books on Malcolm X have appeared, some of which have earned critical acclaim. While I’ve found many of them worthwhile, the book I’m sharing now was published more than two decades ago. I consider it one of the more compelling looks on Malcolm X’s life. Despite it’s relative age, it has left a lasting impression on me, perhaps because of the intimacy it conveyed. “Seventh Child: A Family Memoir of Malcolm X” was written by noted journalist A. Peter Bailey and Rodnell P. Collins, the son of Ella Collins, the influential half-sister of Malcolm X. The memoir was originally undertaken by Ella Collins, tentatively at first in the 1960s. In subsequent decades she began to take notes and record down her memories. Rodnell began aiding his mother in 1984 after he retired from his tennis career. As the years went on and Ella’s health declined, Rodnell’s role in the project grew until he found himself at the reins. Unfortunately, his mother Ella would not see the book come to light as she passed away in 1996, just two years before its publication. It was completed thanks to Rodnell’s collaboration with A. Peter Bailey, also a longtime friend of Malcolm. The memoir draws heavily upon the recollections and accounts left behind by Ella Collins. As a result, an exceedingly close and familial look at Malcolm is provided. Rodnell’s own memories help to paint a vibrant, hagiographically adorned portrait of his mother Ella as well, herself a towering figure who is still all too often overlooked. Originally published in hardback by Carol Publishing Group in 1998 and then in paperback by Kensington Publishing Corporation in 2002, the book has regrettably fallen out of print. It took time to track down, but with some patience and determination I was able find a reasonable copy, reading it through almost immediately. It was worth the time, both the search and the read. I am looking forward to seeing and reading more (isA) of whatever else Rodnell Collins might share in the future of his experiences concerning Malcolm X, his mother Ella Collins, and more.

Ramadan 12

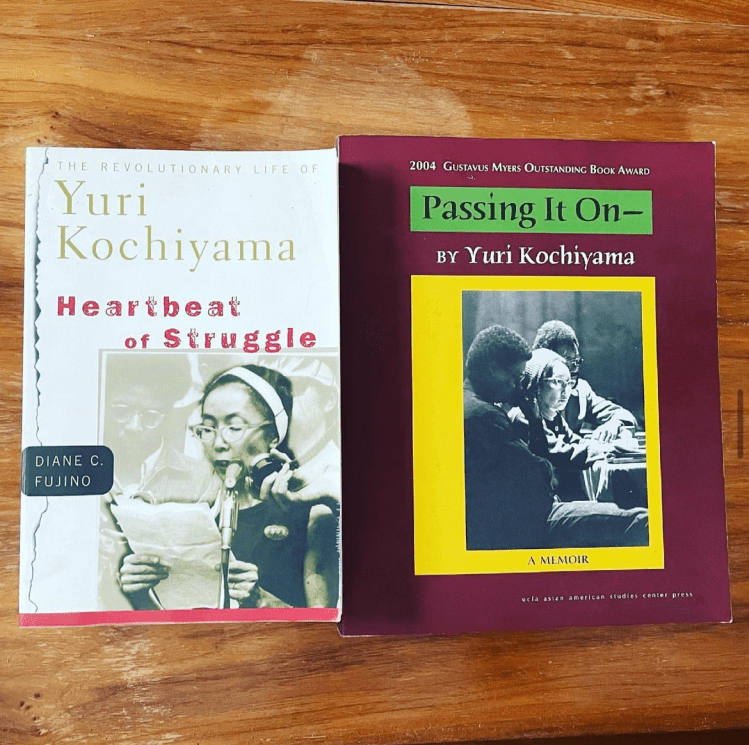

Of the many Asian American organizers and intellectuals of the past, I have found myself most drawn to the exemplary life of Yuri Kochiyama (d. 2014). For many Muslims, their recognition of her is linked to (and often limited to) Malcolm X. Witnessing his assassination on February 21, 1964, she rushed on stage to cradle Malcolm’s head as he lay dying. That tragic moment was immortalized in a now famous photograph. Malcolm X proved pivotal for Kochiyama’s personal transformation. She had first met him the year before and would keep in touch up until his untimely demise. It was her electric encounter him that galvanized her into a community organizer. Her grassroots activism had just begun a couple of years before, all after her family of eight had moved into Harlem. Nevertheless, she threw herself into the work with full commitment, even as she entered her early forties. As she demonstrated, it is never too late to work for change. In the many decades afterwards, she would go on to take part in a broad array of community actions and campaigns for justice. To learn more about her life, I turned to her autobiography “Passing It On-: A Memoir” (2004). The work was gratifying to read, but I detected a noticeable reserve – privacy even – that carefully guarded her words and restrained her disclosures. In fact, thanks to an episode of “Centering: The Asian American Christian podcast,” featuring Grace Kao, I only recently learned that Kochiyama had converted to Islam for a brief time from 1971 to 1975. This important aspect of her life, among many other matters, is discussed more substantively in the other major biography on her, Diane C. Fujino’s “The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama: Heartbeat of Struggle” (2005). I’m looking forward to finding the time to dive into this book more concertedly.

Ramadan 13

James H. Cone (d. 2018) is no stranger to my library. His writing and theology have long been an inspiration, hence my sharing of some of his works last Ramadan. I’m turning to one of his later works now, “The Cross and the Lynching Tree” (2011), for a particular reason. I’m returning to this book for that terrible symbol of white supremacy that decorates the book’s cover and that Cone so dynamically engages within, the lynching tree. I am specifically reading through his invocation of “Strange Fruit” the bitterly poignant song so powerfully performed by jazz singer Billie Holiday (d. 1959). It’s lyrics read as follows:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves, blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant South

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the tree to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop.Many others, aside from Cone, have written on these verses, among the most striking is Angela Davis in her book “Blues Legacies and Black Feminism” (read it but don’t own it). As for Cone, he notes that the original poem that the song was based upon was written in 1937 by Abel Meeropol (d. 1986), a Jewish schoolteacher from New York. Cone writes, “It was fitting for a Jew to write this great protest song about ‘burning flesh’ because the burning black bodies on the American landscape prefigured the burning bodies of Jews at Auschwitz and Buchenwald… Without Billie’s voice, ‘Strange Fruit’ would hardly be remembered. Abel Meeropol wrote ‘Strange Fruit,’ but it really belonged to Billie Holiday, who made the song her own and infused blacks with a militant opposition to white supremacy and found expression in the modern Civil Rights and Black Power movements” (138).

Ramadan 14

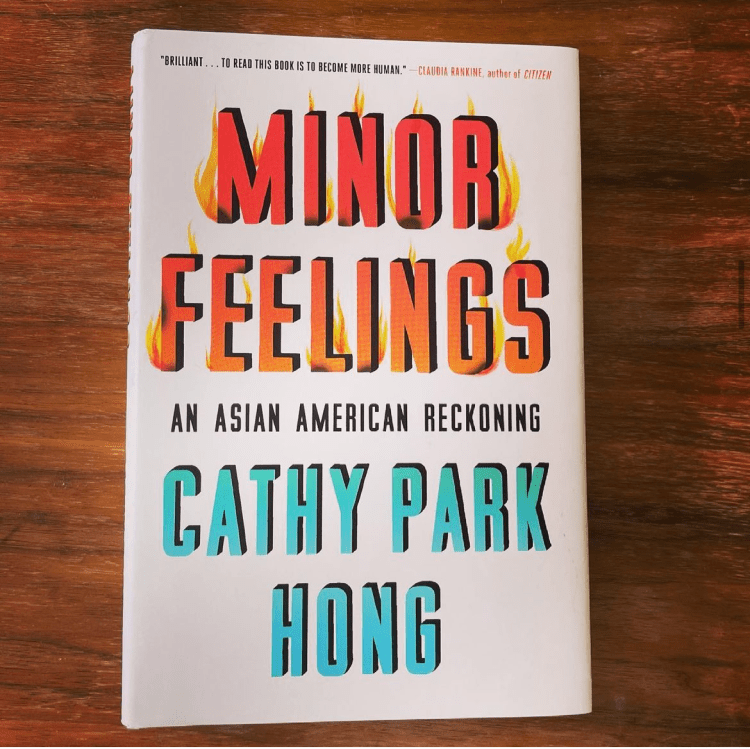

There are times when you want to read words that burn. This was just such a book. Although published in early 2020, Cathy Park Hong’s “Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning” seems like a book written for our present moment in the wake of Atlanta and the nationwide spike in anti-Asian violence. I’m also sharing this book given my recent mention of Yuri Kochiyama, who Hong reflects upon at near the end of her book. Ever attentive to the Asian American experience, each chapter is a powerful exploration of the depths and contours of our present racial landscape from different vantages. Hong does so with personal poignancy, whether she is exploring comedy through the genius of Richard Pryor, her education as an artist among artists, or offering meditatively critical reflections on our current events. While the essays herein have a strong memoir quality to them, she uses each piece to good effect in order to gesture to the larger history of Asian America, at least loosely sketched, and how those stories are tied to other movements and larger forces. The following words struck me especially: “The ethnic literary project has always been a humanist project in which nonwhite writers must prove that they are human beings who feel pain… I don’t think, therefore I am – I hurt, therefore I am. Therefore my books are graded on a pain scale. If it’s 2, maybe it’s not worth telling my story. If it’s 10, maybe my book will be a bestseller. Of course, writers of color must tell there stories of racial trauma, but for too long our stories have been shaped by the white imagination… In many Asian American novels, writers set trauma in a distant mother country or within an insular Asian Asian family to ensure their pain is not a reproof against American imperial geopolitics or domestic racism; the outlying forces that cause their pain – Asian Patriarchal Fathers, White People Back Then – are remote enough to allow everyone, including the reader, off the hook (49).”

Ramadan 15

This past December, for the virtual Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, I was very generously invited to respond to Celene Ibrahim’s recent book “Women and Gender in the Qur’an” (2020). I had the pleasure of doing so alongside distinguished others on a panel. The work is important for surveying, documenting, and critically analyzing the narratives and references to women and gender found throughout the Qur’an. I was particularly struck by Ibrahim’s attention to the language and portrayal of familial relationships alongside her coverage of key figures. It was perhaps the Qur’anic treatment of motherhood that left the most lasting impression on me. I think the work will remain an invaluable source and reference point for those exploring the scripture. Beyond that, of course, I detect something more theological going on between the pages and lines of the text. There are noticeable moments when the pacing slows to facilitate a more discerning degree of interpretative work. Lines are unearthed and drawn and subtle trajectories are traced out. I found these periodic excursions consistently insightful. I am curious, of course, where all this might lead in future works to come.

Ramadan 16

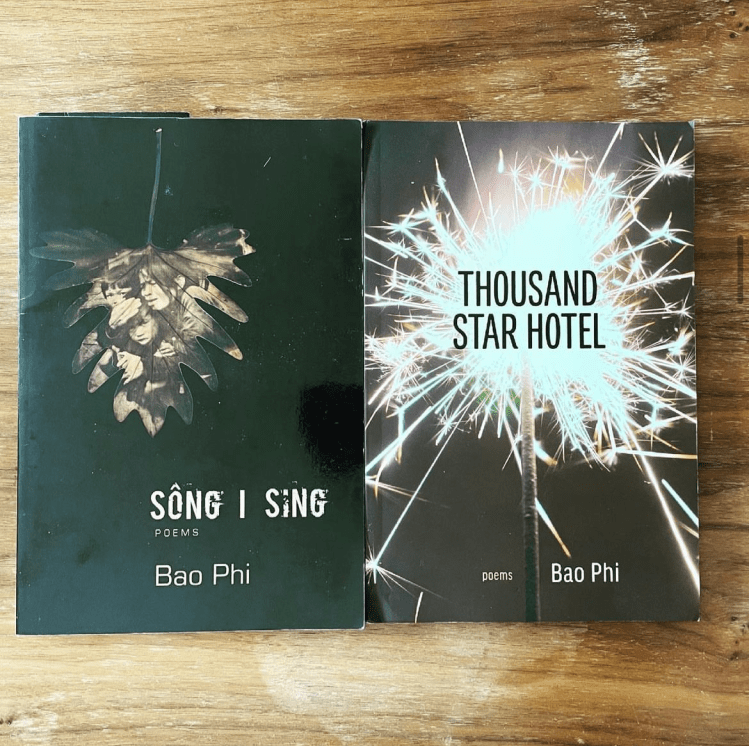

A book I shared last year, Viet Nguyen’s “Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War” (2016) is important for what I’m working on now. But since I’m trying to avoid repeating works, I’m going to share instead, over the next few days, works that I discovered through his book. To start, here are two poetry collections: “Sông I Sing” (2011) and “Thousand Star Hotel” (2017) by Bao Phi, a performance poet, writer, and community organizer based in Minnesota. Given the restrictions of the medium, here are a few stanzas from “For Us” from the earlier book:

From the mud of the Mekong to the bones of the Mississippi

From the dusty winds of Manzanar to the glowing scars of Hiroshima

From the sun in Bombay to the moon in Alaska

From the mists of the Himalayas to the ash of Volcano

From the hills of Laos to the openmouthed mic in St. Paul

From the streets of Seoul to the sidewalks of Tehrangeles

From California shores to New York corner stores

…

This is for you, twisting our names

Into bleached demons so foreign tongues

Could invoke them

Mastering our own blondspeak scrabbletalk

This scored mishmash of grab-bag didactics

Cringing at the sound of our mother tongue’s syllables

This is for you, who use our split lungs as divining rods

To find the flow of our lost languages.

This is for you, whose homes are turned upside down

While men and women debate the sorrows of war

Safe from the scars of barbed wire

For you, whose lands are painted in smoke and bone

Neon bullets ripping through green

Your heart the same shape

As the hole you buried your family in.

This is for you, whose sons and daughters picked up a gun

And wore a flag for the price of college tuition,

As your war stories fell under the noise of the machines

You operate to keep food on the table.

This is for you, shapeshifting evil, taking whatever form

They need for you to be the next enemy

Only loved when you can be used,

Asian people,

Only loved when you can be used.

… (1-3)

The words alone carry immense weight, but hearing them performed adds greater depth given the lyrical way that Phi weaves the tonal quality of Vietnamese into many of his verses. This and more can be found on baophi.com as well as Bandcamp.

Ramadan 17

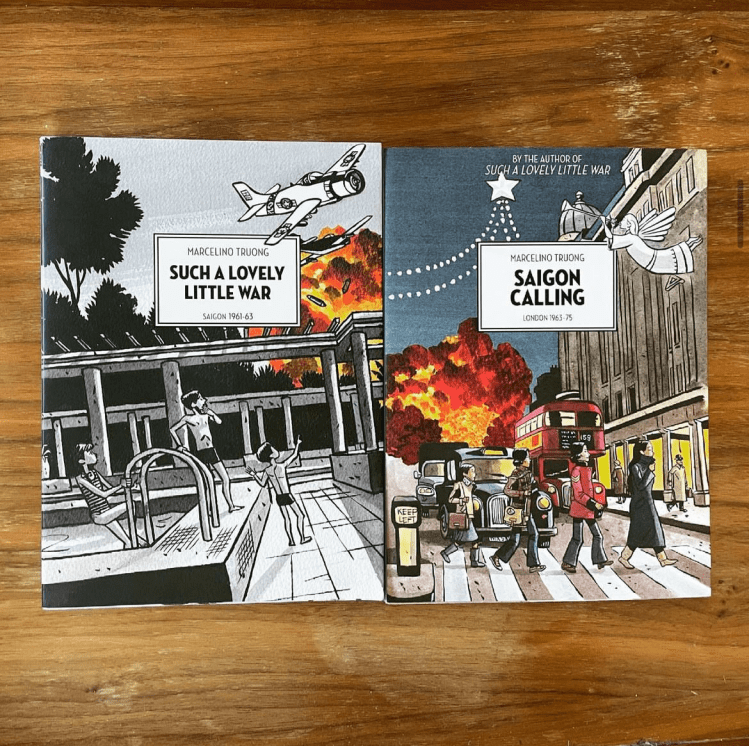

This small excursion into Vietnamese writers is obviously a build up to the fall of Saigon, specifically April 29th which I’ve been trying to mark annually these past couple of years. It was on that precise date that my father fled Vietnam. Of course, his flight was but one of thousands. Many tried and failed caught in the turmoil of war’s end or finding only their own terrified demise. Of course, the attempts at escape were not pinned solely to 1975, but had been happening for years prior and continued long after as the stories of many can attest. The literature of these lives has grown steadily over the decades and I’ve been diligently working my way through whatever comes my way. I’m featuring today two graphic novels by Marcelino Truong, who left Vietnam years before the end of the war, but whose life remained rocked by its turbulence. Truong is biracial, his mother French, his father Vietnamese. Moreover, his father was a diplomat for the government in the South, which led to his family crossing the globe during this time. Serving for a time in Washington, D.C. the escalation of the war drew Truong’s family back to Saigon, a period of his boyhood recounted in “Such A Lovely Little War, Saigon 1961-1963” (2016). After two years, an opportunity to work for the Ambassador in London arose, which his father seized as the family experienced the horrific heightening of the war. Truong continues his recollections in the second volume, “Saigon Calling, London 1963-1975” (2017), which takes us through to the end of the war. The books were originally published in French, in 2012 and 2015 respectively. While the fortunes of Truong’s family differed dramatically from those of my parents, it was helpful for getting a better sense of the range of experiences of those who lived through the war.

Ramadan 18

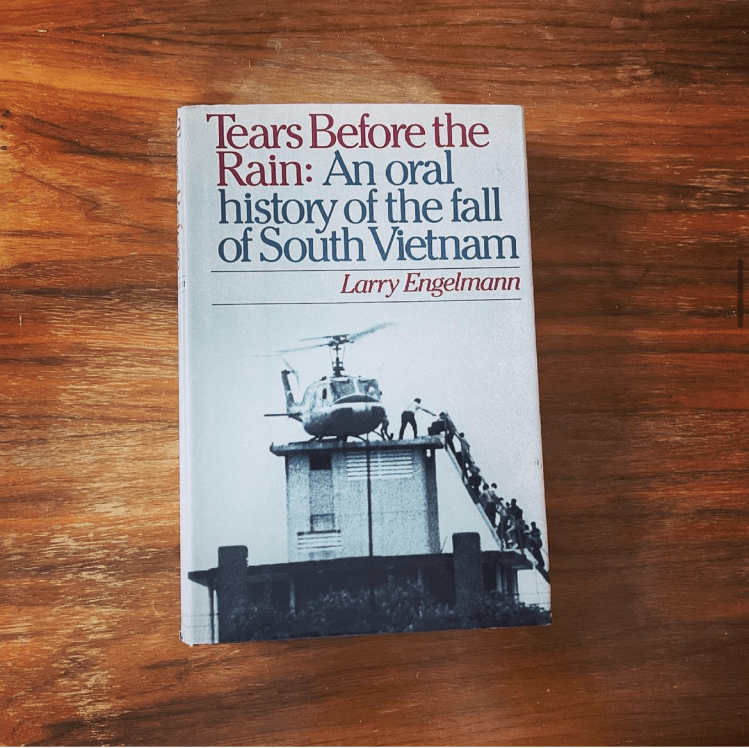

To mark the day that Saigon fell here is “Tears Before the Rain: An Oral History of the Fall of South Vietnam” (1990) by Larry Engelmann. Aside from the Preface, the author has little to say himself. Instead, he presents here the testimonies of some seventy persons who lived through the war. Painstakingly interviewing and transcribing their stories and recollections, Engelmann shares an array of perspectives. While the preponderance of voices represented are Americans unsurprisingly, he nonetheless makes the effort to capture Vietnamese voices as well, from both the South and North. It was because of this special attention that I first turned to this book. He speaks with those who were children at the time, those who were fleeing civilians, as well as the supposed “Victors” in order to capture their hopes and anxieties, wounds and regrets, and curated memories along the way. What follows is an excerpt from an account left by Nguyen Truong Toai. Having served in the ARVN, Army of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), Truong ended up spending three months in a re-education camp at the war’s end. Then, in 1979, he fled by boat to the Philippines with nothing more than a military compass in hand. Eventually, he made it to the U.S. He confesses: “Of course, I dream of Vietnam. A strange dream. I dream about going home and getting near my house. But then, in my dream, I am too afraid to go into it again for some reason. Maybe because I am afraid of Communists’ capturing me again. When I wake up I feel regretful. I think to myself, ‘I was so close to my home in my dreams, but I couldn’t go inside again.’ Even in my dreams I can’t really go into my house in Vietnam and live peacefully again” (240).

Ramadan 19

Some books feel destined to survive to live their own lives. “Last Night I Dream of Peace: The Diary of Dang Thuy Tram” (2007) is one such haunting work. Đặng Thùy Trâm, born in Hanoi, was the young woman who penned this book. By the age of 24, she was committed to the cause of the revolutionary North to reunite Vietnam and liberate her people. After completing medical school, Thuy marched south on the Ho Chi Minh Trail to Quang Ngai province in order to run a secretive emergency medical clinic. She went out of patriotic fervor, but she also went, as we learn from her diary, out of love. From her hidden site, which was forced to relocate many times, Thuy treated both local villagers and wounded soldiers. Throughout this stressful time, she kept a diary of which only two volumes survive. They cover 8 April 1968 to 20 June 1970, the date of her last entry. What happened after? “…several days later she was found…” the introduction discloses, “…dead with a bullet through her forehead” (xv). She was killed by American forces operating in the area.

Later that year, Fred Whitehurst, an American soldier, was tasked with going through captured enemy documents. “One day, he was throwing documents into a fire in a 55-gallon drum, when his interpreter, Sergeant Nguyen Trung Hieu, said over his shoulder, ‘Don’t burn this one, Fred. It has fire in it already.’ Startled, Whitehurst saved the document – a collection of pages sewn together with a cardboard cover, no bigger than a pack of cigarettes” (xvi). He returned home, filed the diary away, nearly forgetting about it, and went on to become an FBI forensics expert. In 2005 he gave the diary to an American veteran who was planning a trip to Hanoi. His hope was to return the diary to Thuy’s family. The veteran did. Thuy’s mother and three surviving sisters celebrated the diary’s miraculous return 35 years later. It was published that same year and sold like wildfire across Vietnam. It lit the imaginations and souls of people across the country, young and old. Two years later it was translated into English, the book before you now.

Many times Thuy’s thoughts read like poetry. Her idealism, dreams, and kindheartedness exude from every page as do her concerns, struggles, and secret fears. Her words shine with a luminosity that the young so readily carry. While working with the stories of my parents I knew I could not restrict myself solely to the voices from the South. Her diary, then, felt like a necessary measure in that regard.

Ramadan 20

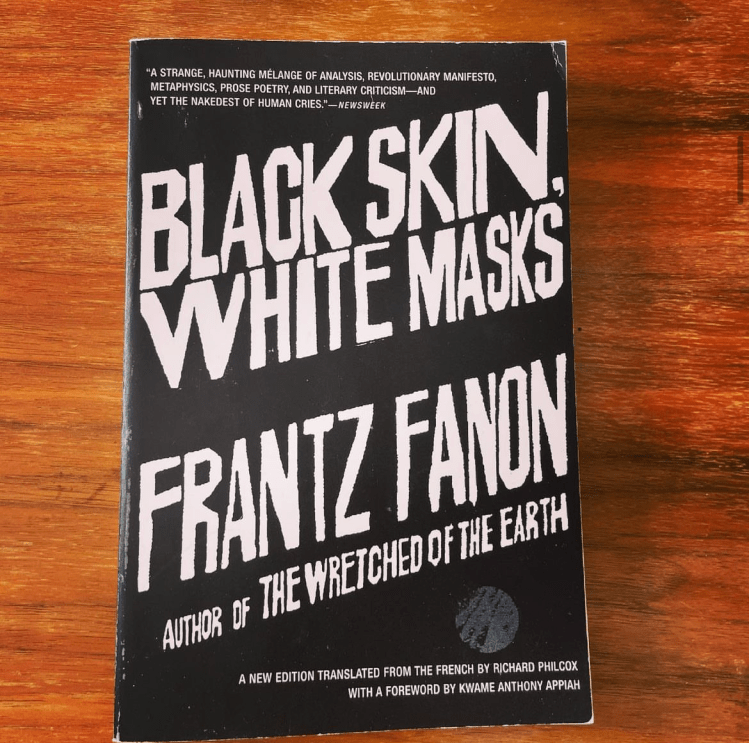

Shortly after last Ramadan I shared “The Wretched of the Earth” by the revolutionary thinker and psychiatrist from Martinique, Frantz Fanon (d. 1961). His notion of “the Wretched,” literally les Damnés in the original French, will figure into what I write next, among other issues and critiques that he raises in that book. Yet as important as that work is, which was published in the last year of his life, I will also be turning to this one, his first, “Black Skin, White Masks” for the critical exploration of blackness under the white colonial regime that unfolds within. Originally written in 1952, this newer English translation by Richard Philcox was published relatively recently in 2008. I can’t say, however, how it compares to the earlier 1967 translation by Charles Lam Markmann. Insight on this front would be appreciated. I should also note, that I feel compelled to feature this book now in my Ramadan series since so many of the upcoming authors I hope to feature here (isA) pointedly draw upon Fanon’s works and engage with his ideas in incisive and insightful ways.

Ramadan 21

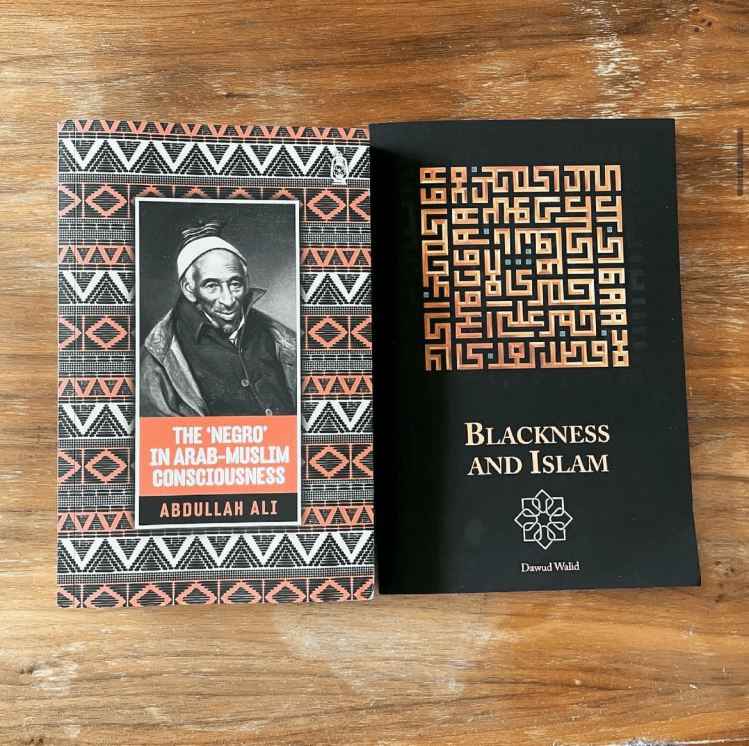

Race, global white supremacy, and systemic evil figure centrally in the ethical critiques and theology that I’ve been endeavoring to articulate. As a result, I’ve been working through the critical and thought provoking scholarship that wrestles with, engages, and deconstructs the prevailing ideas and forces on that front. As I tackle this, I’ve also been specifically interested in what the broad array of Muslim voices has to say about modern structural racism or aspects thereof. Here are just two works from that spectrum that have appeared in past years, one quite recently. The first is Abdullah Ali’s “The ‘Negro’ in Arab-Muslim Consciousness” (2018), which explores how notions of race were expressed and articulated in the historical context of early Islam, the hadith literature, legal traditions and so on. This, at least, is what I’ve gleaned from my reading of the first two chapters. The other work, which I haven’t had an opportunity to dive into properly yet, is Dawud Walid’s “Blackness and Islam” (2021), which turns to figures found in the Qur’an and those around the Prophet Muhammad who are ascribed blackness and how the associated descriptors are understood.

Ramadan 22

Here are two authors that I’ve mentioned in passing before. Given my recent discussion of Fanon, I wanted to share these two soon afterwards. I first encountered Nelson Maldonado-Torres through an article of his in the journal Cultural Studies entitled “On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of a Concept,” which was my introduction to this powerful idea. Because of that piece, I then turned to his book “Against War: Views from the Underside of Modernity” (2008) where he develops a religious ethical critique of European modernity based on the thought of three pivotal thinkers: Emmanuel Levinas (d. 1995), Frantz Fanon (d. 1961), and Enrique Dussel. Paired with this work is an earlier work of Walter D. Mignolo, “Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking,” (2000) which is an in-depth exploration and critical analysis of the coloniality of power. Since this work, of course, Mignolo has gone on to write much else, especially with respect to decolonial studies. For purposes of my own work, both authors have been incredibly helpful for thinking through a host of issues, from ethics and structural oppression to life along the borderlands.

Ramadan 23

“The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century,” by Asian American philosopher and social activist Grace Lee Boggs (d. 2015), was one of those books that I read out of pure personal interest. I have two stacks of books that I keep: one made up of far-too-many works that I ought to read given whatever I’m working on and another of books that I’ll turn to every so often just for a change of pace. This is from the latter. I had heard about Boggs in passing, but hadn’t taken the time to look more closely at her life or her works. In fact, it was her connection to Malcolm X, which she writes about in here, that was likely my initial draw. In any event, an opportunity arose to finally pick up this book and read it. Unsurprisingly, it went rather quickly. In addition to her personal memories and reflections on a life well lived, she shares the work that she has done and maps out what work remains for the betterment of our communities. Rather than residing in the realm of the theoretical, her words are grounded in a praxis long nourished by the ground of community engagement. It was both refreshing and inspiring to dive into a book that was so lucidly told and so firmly grounded in the wisdom of lived experience. Of course, I discovered soon into my reading just how relevant her writings were for my present endeavors. A few choice lines:

“The social activists among us today struggle to create actions that go beyond protest and negativity and build community because community is the most important thing that has been destroyed by this dominant culture” (43).

“…since discovering that the personal is political, women activists have been abandoning the charismatic male, vertical, and vanguard party leadership patterns of the 1960s and creating more participatory, empowering, and horizontal kinds of leadership. Instead of modeling their organizing on the lives of men outside the home – for example, in the plant or in the political arena – they are beginning to model it on the love, care, healing, and patience that, along with an appreciation of diversity and of strengths and weaknesses, go into the raising of a family” (173).

Ramadan 24

This isn’t a new book to me, but one I’m revisiting at the moment. Sohail Daulatzai’s “Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom Beyond America” (2012) was an important read for me when I first encountered it. In the first chapter, the book clearly sets Malcolm X and all that would emerge after him in a definitively international context. I still assign this first chapter every time I teach my Islam in America course. It helps to dispel the tunnel vision that is written into the autobiography. As for the book as a whole, it examines “the political and cultural history of Black Islam, Black radicalism, and the Muslim Third World in the post-World War II era, when Black freedom struggles in the United States and decolonization in the Third World were taking place” (xiii). I’ve found myself continually returning to Daulatzai’s dynamic idea of the imagined Muslim International as well. Through it, the work dismantles the façade of exceptionalism that beleaguers so much American thinking. Some choice words from the Epilogue:“For Muslims in the United States, Malcolm’s political vision has challenged all immigrants – especially those from the Muslim Third World – to resist the seductions of the label American and the domestication of their politics within a national framework. For just as the embrace of ‘Negroes as Americans’ and Civil Rights failed the ideal of Black equality, the embrace of a ‘Muslim-American’ identity and the desire to be a ‘good citizen’ and achieve ‘honorary whiteness’ ultimately conforms to a dangerous and dubious model of liberal multi-culturalism, ‘diversity’ and anti-Blackness. For to be a ‘Muslim-American’ is to embrace an identity and a politics that is nationally bounded and that seeks acceptance and inclusion instead of addressing the very forces that excluded Muslims in the first place and that led to racial profiling, deportations, surveillance, and war: namely, white supremacy, militarism and capitalism” (194).

Ramadan 25

Today’s work is an extraordinary book on many counts. “We Do This ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice” (2021) brings together the powerful words of Mariame Kaba, the New York City-based educator and community organizer. Dedicated to prison abolition, Kaba has developed a strong media presence to match the critically incisive and organizationally instructive essays that she has penned and the compelling interviews that she has conducted over the years. This book is the first attempt to bring together her continually growing body of advocacy and activism. Notably, its aim is not to paint a portrait of the woman behind these words, but to center the movement to which she is tirelessly dedicated and to delineate the paths of action that we ought to explore and pursue. I come to Kaba’s work a newcomer and I have only just begun to read through it. Nonetheless, I am already seeing a commitment to a cause that is resonant with and reminiscent of several community organizers of past generations that I admire and have tried to cover in this space. From the essay opening the book:

“However, some might be wondering, ‘Is abolition too drastic? Can we really get rid of prisons and policing all together?’ The short answer: We can. We must. We are. Prison-industrial complex abolition is a political vision, a structural analysis of oppression, and a practical organizing strategy” (2).

“Let’s begin our abolitionist journey not with the question, ‘What do we have now, and how can we make it better?’ Instead, let’s ask, ‘What can we imagine for ourselves and the world?’ If we do that, then boundless possibilities of a more just world await us” (3).

Ramadan 26

The Iranian intellectual and revolutionary Ali Shari’ati (d. 1977) has long been an intellectual presence. I was first exposed to him and his thought around the same time as my initial academic introduction to Islam during my undergraduate days so many years ago. His words back then were decisive and critically compelling. As I shift my work more concertedly now to questions of structural oppression, Shari’ati has reemerged with a particular brilliance. Of course, I’ve had to rely on those works that have been translated into English from the Persian as well as those few studies dedicated to him. The book on the left, “On the Sociology of Islam: Lectures by Ali Shari’ati” (1979), collects several of his lectures, which have been rendered into English by Hamid Algar. I have long owned this one. I recall ordering it shortly after first learning about Shari’ati. Alongside it is another work of his that was developed out of his pilgrimage experiences to Mecca, which is appropriately entitled “Hajj” (1977). While that book is old as well, I picked this up more recently, perhaps only a decade ago during one of my used books expeditions. As I wrote my second chapter on systemic evil, it was Shari’ati’s reimagining of the story of Cain and Abel that precipitated my own theological reformulation of that narrative. While he addresses it in “Hajj,” here is a passage from “On the Sociology of Islam” that invokes that same powerful story: “Man begins with the struggle between spirit and clay, God and Satan, within Adam. But where does history begin? What is its point of departure? The struggle between Cain and Abel. The sons of Adam were both men, human and natural, but they were at war with each other. One killed the other, and the history of humanity began” (98).

Ramadan 27

I share these three books for their common theme of resistance. In “Slave Rebellion in Brazil: The Muslim Uprising of 1835 in Bahia” (1993), the author João José Reis offers a careful historical study of the famed rebellion named in the subtitle. The work is meticulous in exploring the broader world and context in which the uprising erupted. As a historian, I can appreciate the author’s painstaking attention to the various details on the ground as well as the larger forces at work. Next to it is a more recent acquisition, one I have yet to properly explore. Habeeb Akande’s “Illuminating Blackness: Blacks and African Muslims in Brazil” (2016) similarly covers the rebellion in one of its chapters. That treatment, however, is part of a much larger exploration of and reflection on blackness and Islam in the Brazilian experience, matters of which I am entirely unfamiliar. With respect to the 1835 rebellion, Akande notes that it was planned to coincide with the 25th of Ramadan as well as a Catholic holiday pinned to January 25th (191), thus my sharing of these texts in these last few days. Finally, I’m include alongside these two books Walter C. Rucker’s “The River Flows On: Black Resistance, Culture, and Identity Formation in Early America” (2006). While the presence of Islam and Muslims in this work is decidedly muted, I felt it worthwhile to read more broadly to understand similar uprisings in North America.

Ramadan 28

I have found Vincent Lloyd’s “The Religion of the Field Negro: On Black Secularism and Black Theology” a powerful and provocative work. In it, Lloyd levels a critique against secularism for its domestication of theology, while also raising difficult, but constructive questions for its future trajectory, black theology particularly. Beginning with Malcolm X (d. 1965) (hence the title), Lloyd engages with many voices in the course of his book, like Ella Baker (d. 1986), James Baldwin (d. 1987), James Cone (d. 2018), Sylvia Wynter, and Achille Mbembe. One of the matters I appreciate most about the work is its unapologetic concern for theology, to restore it to its rightful place and orientation. Here is a compelling passage from the Introduction: “The difference between the critic and the theologian is that the theologian does the work of the critic, challenging idolatry, but also something else. From the critic’s perspective, this something else is an illicit belief in God. From the theologian’s perspective, when theology is rightly understood, this something else is a commitment to hold up the wisdom of the marginalized. (From the theologian’s perspective, this is another way to proclaim her belief in God.) That theologian views the critic as ultimately an elitist, one who never really renounces whiteness, its sustaining institutions and networks. The practice of criticism as it is understood in the academy is an elitist practice, made possible by elite institutions, practiced by those in the 1 percent – if not of financial capital, then certainly of social and cultural capital. In contrast, the practice of theology is humbled by its extra belief in the authority of the poor. For the theologian, at her best, one foot is in the world of the elite and the other foot in the world of the afflicted… Her scholarship always pairs criticism with stories of those on the margins whose wisdom is greater than the scholar’s, those whose capacity to see through the illusions of power has not been dampened by the comforts of the elites” (11).I also found this passage on race and secularism from the preceding page similarly poignant: “The stories of secularism and racism are entwined. Histories could be written, and have been written, about how religion is thematized at the moment of the colonial encounter, at the moment when race takes on its modern significance. Religion and race come into the world at once, and theology is left behind. The worldly powers that fuel colonialism and empire use both whiteness and religion as tools of conquest and management. Theology at its best, critical and marginal, suffocates under the control of worldly powers” (10).

Ramadan 29

While the apartheid state of Israel continues to relentlessly pursue its ideological end, I thought it appropriate to share today French- Algerian activist Houria Bouteldja’s “Whites, Jews, and Us: Toward a Politics of Revolutionary Love” (2016). I picked this up prior to the pandemic but did not find an opportunity to finish it until after it had settled in. This is both a challenging book and a book intended to challenge, if I might offer such a distinction. Within this concise, modestly sized volume, Bouteldja takes to task the French Left and its supposed commitments. Nonetheless, as I read the work, it was clear to me that its relevance extends well beyond her immediately intended audience. Addressing questions of indigeneity, immigration, and gender as well as the problematics of Zionism, colonialism, populism, and Islamophobia (among other matters) the author articulates a set of challenging critiques from a perspective of radical change. Yet, in voicing her series of critiques, she is, at the same time, posing them almost self-reflexively, to an encompassing community, for at the heart of her work I see a constructive effort of building towards revolutionary, collaborative possibilities. Just one passage I found striking, “The power of imperialism is such that all the phenomena that structure the Western political, economic, and cultural field impose themselves across the world more or less contentedly: sometimes they come up against the resistance of the people, sometimes they penetrate, slide in like butter. They become reality. They inform and shape the everyday” (92).

Ramadan 30

Mohja Kahf’s “Hagar Poems” (2016) is a direct inspiration for a part of my present work. In this moving collection, Kahf brings together an array of poems that imagine, invoke, and draw upon the experiences of women from across scripture, the pious past, and beyond. Their complex relationships and muted lives are brought to life through Kahf’s verses and creative turns. They are given voice and vision, often cast from multiple positions and different angles. Of course, important and incisive critiques permeate the work as well. My main draw, however, was with the titular figure of the collection, Hagar, whose poems amount to nearly the first half the work. I’ve been trying to unearth her under-narrative, to find the latent story that is there between absent lines, to imagine what her life was like amidst and after it all. To that end, the scholarly literature on Hagar is considerable and growing (and I’ve been going through that too), but there was something powerful about starting my inquiry from an imaginative and poetic vantage. What Kahf offers is a truly vibrant spread of poems exploring Hagar (and others) in ways so rarely fathomed despite their relatability and relevance. Here are a few lines that have lingered long in my mind from “Hajar’s Ram”:

“Maybe Hajar’s ram was the miracle

of the rest of her life. First finding

the will to live, cut off and alone,

then foraging in the desert

for a new sort of family,

one not based on lineage or ownership

or an identity foisted on you like a mask,

but the kind of family that sticks with youeven when you become a pariah… (18)”

Eid

Earlier this month, on the 7th of Ramadan, we witnessed the passing of our beloved Sohaib Sultan. Now with Ramadan having come to a close and the day of Eid al-Fitr upon us, I wanted to share a few marks of his legacy. While Sohaib has left behind an astonishing and inspiring collection of audio and video recordings capturing his thoughts, reflections, prayers, wisdom, and humor, he was also an author, a writer of the word as his final essays on Medium compellingly and honestly attest. As I went my through my library this Ramadan, I came across his books and felt it only right to share those books of his that I own with you all today. The last time I saw him in person, we talked about some of these works. In 2004, his first book appeared, “The Koran for Dummies” from Wiley Publishing. He wrote it in his early years of formation, before even starting the Islamic chaplaincy program at Hartford Seminary. A few years later in 2007, Sohaib wrote “The Qur’an and Sayings of the Prophet Muhammad: Selections Annotated & Explained” with SkyLight Paths Publishing, where he was able to take a more commentarial approach to both scripture and the prophetic tradition. Then, most recently, perhaps around 2017 or so, Sohaib published “Searching for Wisdom: Ruminations on Islam Today” through the Muslim Life Program at Princeton University, where he spent so many years in faith-filled service. Collected in this volume are many of his published pieces and shorter reflective essays. Over the course of its pages he engages with a wide range of topics with his characteristic sensitivity and balance. As I look over these works, I can see the threads that would develop into the sincerity, expansiveness, and joy that Sohaib so richly embodied and exuded up until his final days with us. May we come to understand and live those same qualities ourselves each in our own way. Eid mubarak to all those celebrating and peace and blessings to all.