By its third year, the Ramadan daily book share has become a tradition as well as a welcome undertaking on my part. This year collects both new acquisitions and scholarly engagements at the time. Back to the MRB.

Ramadan 1

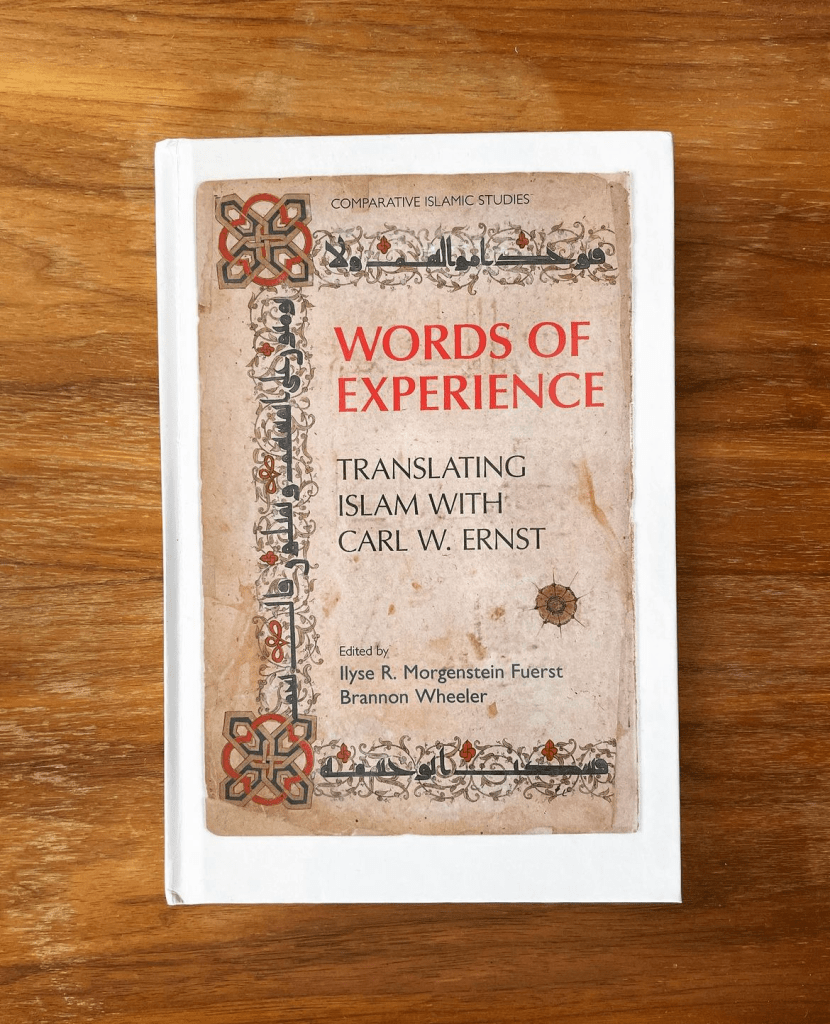

Ramadan Mubarak to you and yours. I’ll try to continue this year (insha’Allah) my tradition of sharing a book (or so) each day through to Eid. I’ll try to prioritize recent acquisitions, but will chase an occasional tangent every so often into the deeper past. Today I begin with the works of Carl Ernst, whose scholarship was quite formative for my studies. I had the opportunity to review recently this book, “Words of Experience: Translating Islam with Carl W. Ernst,” featured in the first photo and expertly edited by Ilyse R. Morgenstein Fuerst and Brannon Wheeler. Bringing together papers from a conference honoring and building upon Ernst’s ongoing legacy, the pieces within surface compellingly and insightfully the incredibly important ways that Ernst has impacted Islamic Studies and Religious Studies more broadly, while making important interventions on their own. I say more in my review, but those truly interested would be better served by simply reading the volume itself. Joining this book are several other works, in the second photo, that have accompanied me throughout the years. Yet, as those familiar know, there is an impressive array of articles and essays that are also an important part of Ernst’s impressive scholarship thus far that is difficult to display in a space like this. May this month be one of blessing. Ramadan 1

Ramadan 2

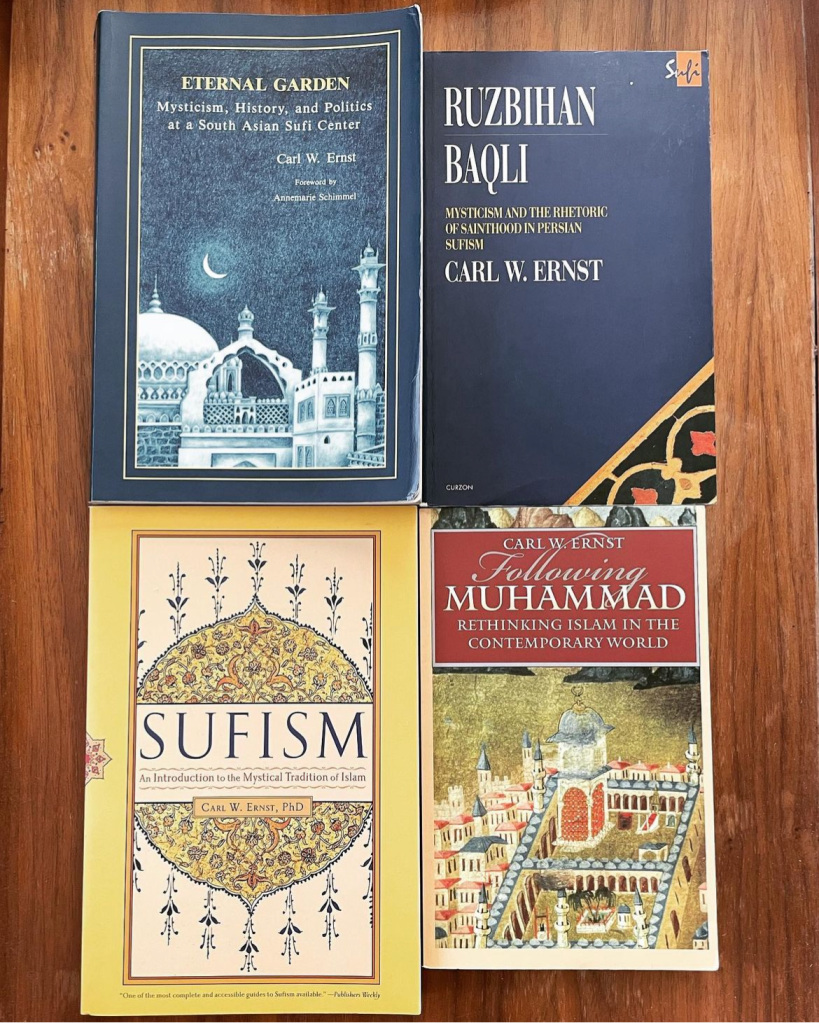

Given the constraints of time and the many books that call out for attention I find myself hard pressed to read a novel these days unless recommended as truly remarkable. Thanks to a Facebook exchange I came across, I decided to read Fatima Mirza’s “A Place for Us” very recently (h/t Roshan Iqbal and Danielle Widmann Abraham). It was time well spent. I was utterly engrossed finding myself constantly returning to the lives of the characters within the book rather than the pages of other works. The book’s gravity has less to do with the saga itself, than with the intricate parsing of the family narrative – like so many half-shared memories falling into poignant place. In some respects, this could be the story of any family, while at the same time the worn scars of a distinctly American Muslim one. In sum, it is a tale carefully told to beautiful effect. Ramadan 2

Ramadan 3

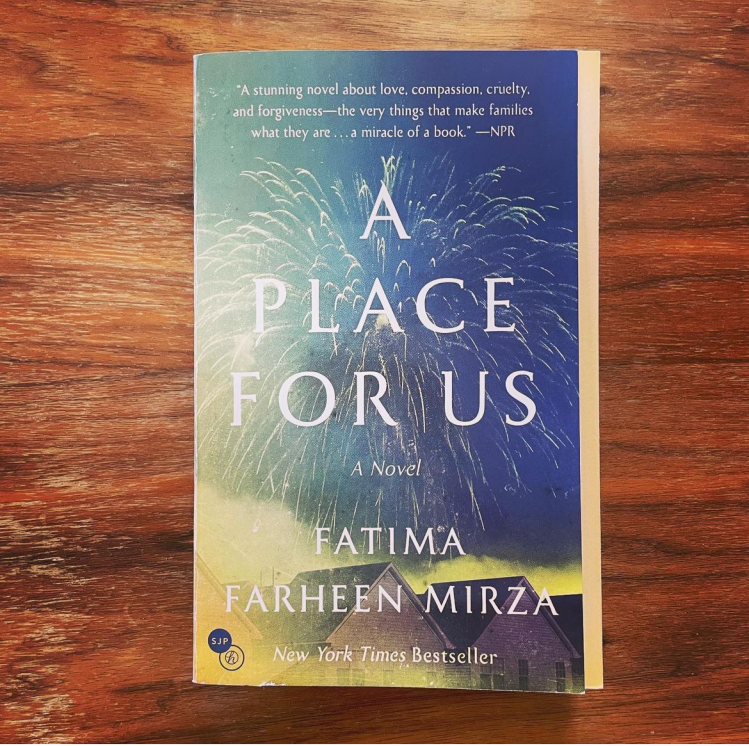

As I turn back to my ongoing work on religion, mass migration, and race I’ve been gathering works that give voice to the panoply of experiences that emerge from that intersection. This work, “The Good Immigrant,” edited by Nikesh Shukla, brings together artists, writers, and other creatives from across Britain to do just that. The book came out back in 2016 but I just picked it up this year. Shukla has gone on to produce a volume for US voices as well, though I haven’t picked that up yet. I wanted to start instead with the original publication and have appreciated the essays within even if religion does not figure into them all. I was especially drawn to Vera Chok’s piece on perceptions of “Chinese” and “Asian” in the British context. Also having just shared Mirza yesterday I thought it appropriate to follow with a work containing Riz Ahmed (see what I did there), who writes an especially compelling essay himself. Ramadan 3

Ramadan 4

As of late, I’ve been thinking and writing on the power of the spoken word. While deeply rooted in another tradition, I have appreciated what this slim volume brings together in that vein. The book “Scandal of Redemption” offers selections from the diary entries and homilies of the late Oscar Romero (d. 1980), who was assassinated for his preaching and opposition to injustice in El Salvador. His words were not only delivered from the pulpit but broadcast regularly over the radio to address all, the oppressed and the oppressors alike in their manifold forms. A few choice excerpts: “The redemption planned by God is reaching all people without exception. It is reaching even those who feel they are sinners, those who feel that their sins are unforgivable. Who knows if my words are reaching the person whose hands are bloody with Father Grande’s murder or the one who shot Father Navarro? Who knows if I’m being heard by those who have killed and tortured and done so much evil? Listen, there in your criminal hideouts! Perhaps you are already repentant. You too are called to forgiveness! Whenever I have cried out against violence, I have always added something about repentance for your sins so that you become children of God” (44). “Those who do not pray because they kneel down before the god of materialism – be it money or politics or anything else – have not understood the true greatness of being a human person. To pray is to understand that this mystery of my existence as a man or a woman has limits, but precisely at those limits begins the infinite essence of the One with whom I am able to dialogue… This is the ability to pray, the ability of human beings to understand that they have been made by someone powerful, but that they have been elevated to be interlocutors with their Creator” (113). Ramadan 4

Ramadan 5

Next week I’ll be traveling to to Butler University in Indianapolis to engage with Brent A. R. Hege, the author of this book “Faith, Doubt, and Reason,” in a theological conversation sponsored by the Muslim Studies Endowment there. The event has been some time in the planning, since my last round of book shares last Ramadan in fact, and has weathered some rescheduling thanks to the pandemic. Nonetheless, I’m thankful to see it on the horizon (isA) and grateful to Nermeen Mouftah for organizing it all. As for the book, it is an accessible, but also careful exploration of the three titular subjects and how they interrelate with respect to a purposeful and meaningful life, from a Christian vantage at least. It is clearly concerned with reaching the broader community, a concern too often overlooked by those of us in the academy. I’m looking forward to speaking with Brent on these matters and more in the days ahead as we pass through this holy month. Ramadan 5

Ramadan 6

I ran across a piece on race written by Danté Stewart earlier this year that was powerful and moving. When I discovered it was drawn from his new book “Shoutin’ in the Fire: An American Epistle” I sought it out and read it. Speaking as a Black Christian in America, Stewart presents this book as both a memoir and a ranging interrogation of Christianity, race, and racism in the contemporary United States. There are moments when his words are truly incandescent, others when they burn. Although Stewart is a relatively young voice, studying at the Candler School of Theology at Emory presently, he brings many important issues to the surface in an genuinely honest and personal way. It is a strong debut work and I look forward to reading more of his compelling prose and theological reflections in the future. Ramadan 6

Ramadan 7

This book is part of a growing series aimed at bringing the works and teachings of a contemporary Moroccan Sufi sage, Shaykh Mohamed Faouzi al-Karkari, into English. Yousef Casewit has been diligently at work translating several of these volumes. While I have not had the opportunity to acquire or look through the other books presently available, I felt compelled to pick up right away this one, “In the Footsteps of Moses: A Contemporary Sufi Commentary on the Story of God’s Confidant (kalīm Allāh) in the Qur’ān.” Given my focus on the Prophet Moses and Pharaoh in my writing as of late, I was interested to read al-Karkari’s insights concerning both figures. The original book in Arabic (published in 2016) gathers spiritual discourses on the subject that the Shaykh delivered semi-regularly on Fridays from April to November of 2014. All too often our notion of Sufism is one of wisdom and works crystallized in the deep past. This work and it’s companions are a welcome reminder of the continued life and luminosity of this tradition in our here and now. Ramadan 7

Ramadan 8

Published earlier this year, Jonathan Tran’s “Asian Americans and the Spirit of Racial Capitalism” is a brilliant book, one that I’ve been suggesting to others. Committed to the critique and dismantlement of structural racism in the United States, Tran seeks to complicate the present antiracist discourse by critically analyzing two distinctive, but telling Asian American communities. Even if you’re not drawn to either of these extended case studies, I highly recommend the beginning of the book where the author takes to task what he sees as the predominant identarian antiracist discourse offering instead an “antiracist approach focused on political economy” (13). Whereas the former pushes capitalism’s complicity out of frame, so to speak, the latter centers its critique squarely on it. What is also not apparent from the title, but is evident throughout the book’s pages is that this is a work of theology. For Tran, it is precisely the political economy of Christianity that ought to serve as the ground and vision for antiracism. As a Muslim thinking through similar questions I have found his argument compelling and helpful for finding some clarity in my own “theologizing” on the matter. Ramadan 8

Ramadan 9

Two years ago I shared quite a few works by J.R.R. Tolkien (d. 1973), or simply “the Professor” as he is more affectionately known. I wanted to share today two books that I’ve recently acquired that are deeply connected to Tolkien in some way. The book on the right is the better known one, “The Nature of Middle-Earth,” which was published late last year with some fanfare and was edited by Carl F. Hostetter. The volume gathers a sizable collection of essays, fragments, and assorted pieces written by Tolkien discussing various aspects of Middle-Earth – all testaments to the deep and philologically-rooted world-building and myth-making that lies behind his more famous writings. This work has been called by some the unofficial 13th volume in the massive “History of Middle-Earth” series that I featured two years ago. That set was carefully edited by his son Christopher (d. 2020) from 1983 to 1996. What this volume and other recent Tolkien publications demonstrate is that there remains a plethora of work to be done on the still unexhausted archive of papers that the Professor left behind. Fortunately, an abundance of scholars have emerged to undertake the task. The other book “Black & White Ogre Country” is a more obscure work that I only discovered last year, although it was originally published in 2009 in the UK. Edited by Angela Gardner with Christopher Tolkien’s permission are childhood stories written by J.R.R. Tolkien’s younger brother Hilary (d. 1976). Scrawled in a blank notebook by Hilary sometime after World War II, these tales draw upon the brothers’ shared boyhood imaginings at play offering a rare glimpse into the fantasies of their childhood. While more difficult to track down, I consider it as worthwhile as the more substantial “Nature” volume. Ramadan 9

Ramadan 10

Last week I finished reading Jocelyn Nicole Johnson’s debut book “My Monticello.” My thanks to Arshad Ali and Maheen Zaman for the recommendation and in reading it together. The book brings together several short stories and a novella, from which the volume derives its name. Unfortunately, I found the short stories uneven, sometimes unsatisfying even, but there are two bright lights that hold it together. The first short story “Control Negro” is a compelling start, while the novella at the end carries the rest of the work. All of the stories are set in Virginia and the author does a splendid job of bringing her various locales to life. Having been born and raised there, I found her descriptions especially resonant and evocative. Without giving too much away, I’ll share two things about the novella “My Monticello.” First, it is thoroughly engrossing and reads cinematically. Second, it is set in Charlottesville, the home of the University of Virginia, my alma mater, in a world falling apart as the forces behind the white nationalist rally of 2017 have now crested into a tidal wave. The tale that is told is troubling in many of the right ways. While not a major focus, the most poignant part for me was how utterly impotent and irrelevant the university was in the unfolding tale. Ramadan 10

Ramadan 11

I found this pair of volumes at Grey Matters, a pretty fantastic used book store in New Haven. Before this satellite branch opened up, I had been several times to the original location in Hadley, Massachusetts just off the road running between Northampton and Amherst. If you can find your way over there, that store is a treasure trove worth scouring. As for the books, this is the two-volume anthology “Reporting Vietnam.” Over the years, we have built up a small collection of choice volumes from “The Library of America” series. Given my interest Vietnam, especially the war era as it relates to my parents’ respective stories, I was keen in seeing the American coverage that this set selects and preserves. Collected in the first volume of this anthology are pivotal and important American news pieces from the decade spanning 1959 to 1969. The second volume extends through to the end of American involvement in the war, 1969-1975. Here’s a passage from the second volume from Philip Caputo from April 1975: “I am writing under the pressure of those bursting shells. Pouring over the river bridge is another kind of stream, a stream of flesh and blood and bone, of exhausted, frightened faces, of crushed hopes and loss. The long relentless column reaches forward and backward as far as the eye can see, for miles and miles and in places 50 feet across. These are the thousands upon thousands of Vietnamese refugees fleeing the fighting in Trang Bom, east of here, the shellings in Long Thanh, south of here, the attacks near Bien Hoa, north of here… Many of them are refugees two and three times over – people who ran from Xuan Loc, from Da Nang and Ham Tan and Qui Nhon” (527-8). Ramadan 11

Ramadan 12

Today I’m in Indianapolis, a city I visit often for the sake of family. While I flew in this visit (and fly out again soon enough), we usually make the trek here by car. During our last long visit this past summer, we stopped in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania for a much needed break. It was in this town that I had the chance to explore Midtown Scholar Bookstore, a used book shop that I was only familiar with through its online presence. It was during that visit that I acquired the present book, Karl Barth’s “Ethics.” As many of you know, I have deep respect for Barth’s theological work despite the differences, both minor and major, that I may hold towards it. “Ethics,” however, was a work I was unfamiliar with so it was a welcome surprise when I ran across it. Published in 1981, this volume brings into English a series of lectures that Barth delivered in Münster from 1928 to 1929 that focused on ethics prior to his turn to systematic theology and his voluminous “Church Dogmatics.” Ramadan 12

Ramadan 13

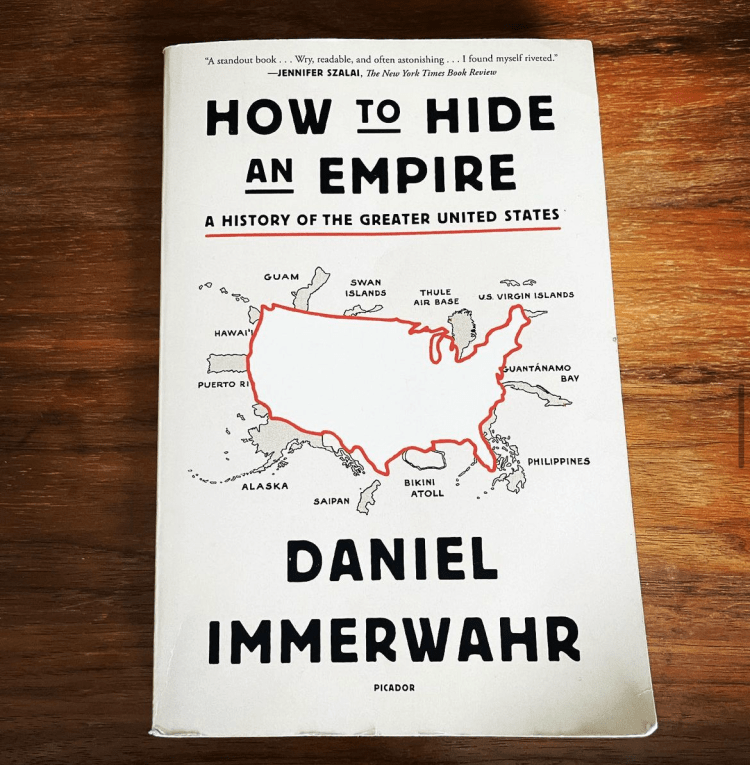

After hearing about the book a couple of years ago, I finally got around to picking up and reading Daniel Immerwahr’s “How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States.” The book is a history of the nation that takes as its primary point of reference the country’s ambiguously held “territories”. The resulting narrative, when strung together and fully told, is a profoundly different tale than the one spun to me throughout my formative years in public school. Immerwahr offers a riveting series of chapters that systematically takes the reader from the nation’s earliest beginnings to the oft-overlooked far reaches of American Empire through to the present. He is an able guide unearthing archives and personalities that help to tell this expansive story in an engaging and memorable way. From maps to language, from guano to military bases, “How to Hide an Empire” is an important read that works methodically, but accessibly to reframe how we conceive of this republic that continues to pretend it is only a reluctant empire. Ramadan 13

Ramadan 14

Given the ongoing conversations currently unfolding for our “Islamic Moral Theology in Conversation with the Future” project, it felt appropriate to pick up this new book from Katrin A. Jomaa entitled “Ummah: A New Paradigm for a Global World.” I have yet to dive into it but do find its premise intriguing. The following summary is shared on the back of the book: “Drawing on theology, history, philosophy, and political science, Jomaa argues that ummah, while often defined as a group of people united by ethnicity or religion, is, in its ideal sense, a community that demands active commitment and a conscious and continuous dedication to the highest moral ideals of that community rather than mere affiliation with a particular set of religious doctrines and practices.” The work looks systematically laid out to explore the concept of “ummah” from a number of important vantages. However it turns out, a new work of what I consider Muslim political theology is always welcome. Ramadan 14

Ramadan 15

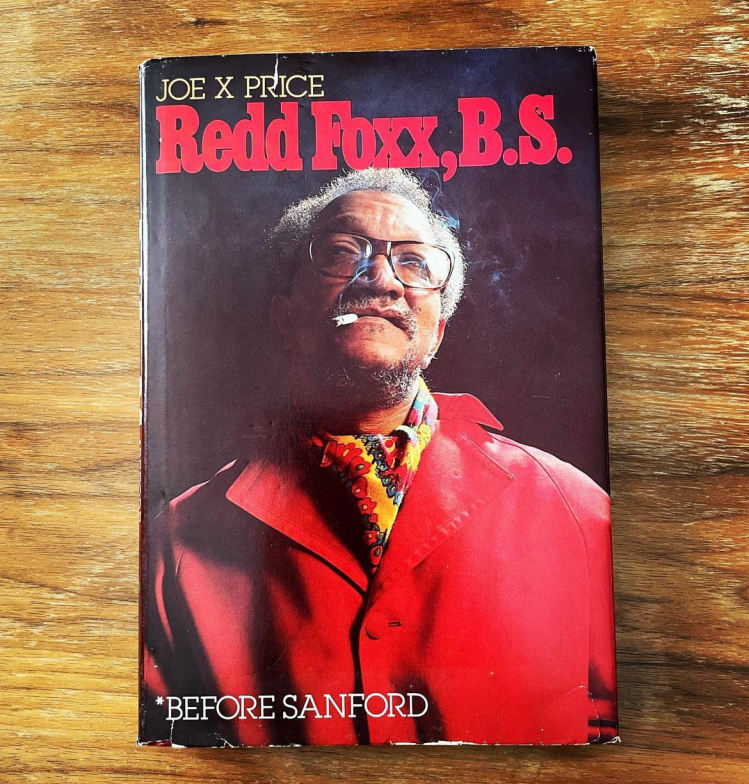

This was a hard book to find. My interest in Joe X Price’s “Redd Foxx, B.S. (*Before Sanford), however, is not about the comedian, but about what Foxx shares about Malcolm X. In Chapter 21 “The Real Sanford,” Foxx talks about his time working and hustling alongside Malcolm X. The passages read as follows: “For a while I was a dishwasher and waiter at Jimmy’s Chicken Shack on Saint Nicholas Avenue. That paid off better. That’s where I met Malcolm Little – known then as Detroit Red and known later as Malcolm X. He was a waiter there, too. He played in the pool hall across the street from 707, where I slept. That was our territory – 145th to 150th Street – so we all used to hang out up there. Malcolm was about the same color as me. You could hardly tell us apart; we both had these conks, and our hair was red with a high pompadour, and we wore the zoot pants – just like the ‘high drape pants’ Billie Holliday used to sing about in her blues. Malcolm didn’t have the show business talent, so he didn’t give a damn what he got into. He’d take on anything to get some dough. He was a little more aggressive; I’d rather miss sleeping with a broad and go somewhere and do fifteen minutes of comedy. One time there was a girl who worked in a cleaner’s. She liked me, so she left the store window open. Malcolm and I went in that night and took about a hundred suits off the racks and put them on the roof. We’d sell one or two of them a day off the roof. We never got caught for that.” (109-110). There’s also the story of Malcolm convincing Foxx to join the Communist Party in order to get the free sandwiches offered down in the Party’s basement (112-113). Finally: “I’m a loner, always have been. I haven’t joined anything and haven’t been asked to join. I never met Eldridge, don’t know Angela, and never even met Roy Wilkins. Malcolm X? Sure, I knew him. I even knew him after he came out of jail and joined up with Elijah Muhammad. We saw each other now and then at his home in the East or at my place out here, but he’d never try to get me involved in any of that stuff” (116-117). I consider the book well worth the long search. Ramadan 15

Concerning the Communist Party story, Foxx ends with the following: “You’d go down there, and you’d dance with the chicks, smell the perfume, and eat the sandwiches. It saved my ass more than once. But what was going on in America wasn’t on Malcolm’s mind or mine. We weren’t into that kind of bag. Not then. Harlem was our world” (112-113).

Ramadan 16

With this 16th day of Ramadan overlapping with Easter, I thought it a good time to feature another Christian theologian whose work I recently acquired and have come to appreciate. This is Wolfhart Pannenberg’s three-volume “Systematic Theology.” I was initially drawn to his works once I learned that he had studied with Barth (though his influences and intellectual debts extend well beyond Barth and Pannenberg does offer critiques as well). My interest deepened when I began to read of his own contributions to contemporary theology. Specifically, I appreciated his notion of “Revelation as History” given my own writings on the subject and continued reflection on the matter. Of course, as a Christian, Pannenberg centers the Resurrection into his conception – hence my sharing this today. While many of his theological contributions were developed in earlier works, this set, written from 1988 to 1994, and translated into English from the original German not long after, represents the maturation of those ideas. I should also say, I typically don’t go for these multi-volume Christian systematic theologies (because who has the time and the shelf space?) but I’m glad to count this among the few exceptions I’ve come to own. Ramadan 16

Ramadan 17

How do I describe a book that defies the expectations of texts? Christina Sharpe’s “In the Wake: On Blackness and Being” is a brilliant, poignant, and incisive examination of black life in the diaspora – a diaspora born from the transatlantic slave trade and passing through the hold of slave ships. In a stunning set of chapters Sharpe explores four different figurations that emerge from out of that experience: the titular “Wake,” “the Ship,” “the Hold,” and “the Weather.” Throughout the work, the author deftly interweaves history, artistry, theory, and memory to stunning effect. There is a breathtaking dynamism that is hard to convey. The book defies easy genre classification given the many things that it does for black life and black death today. I feel this is one of those works that you simply have to read for yourself in order to understand what it does, appreciate its weight, and feel the waves that it sends rippling out. I’ll still share a passage from a section called “Wake Work” in Chapter 1: “A reprise and elaboration: Wakes are processes; through them we think about the dead and about our relations to them; they are rituals through which to enact grief and memory. Wakes allow those among the living to mourn the passing of the dead through ritual; they are the watching of relatives and friends beside the body of the deceased from death to burial and the accompanying drinking, feasting, and other observances, a watching practiced as a religious observance. But wakes are also ‘the track left on the water’s surface by a ship (figure 1.4); the disturbance caused by a body swimming, or one that is moved, in water; the air currents behind in flight; a region of disturbed flow; in the line of sight of (an observed object); and (something) in the line of recoil of (a gun)’; finally, wake means being awake and also, consciousness” (21). Ramadan 17

Ramadan 18

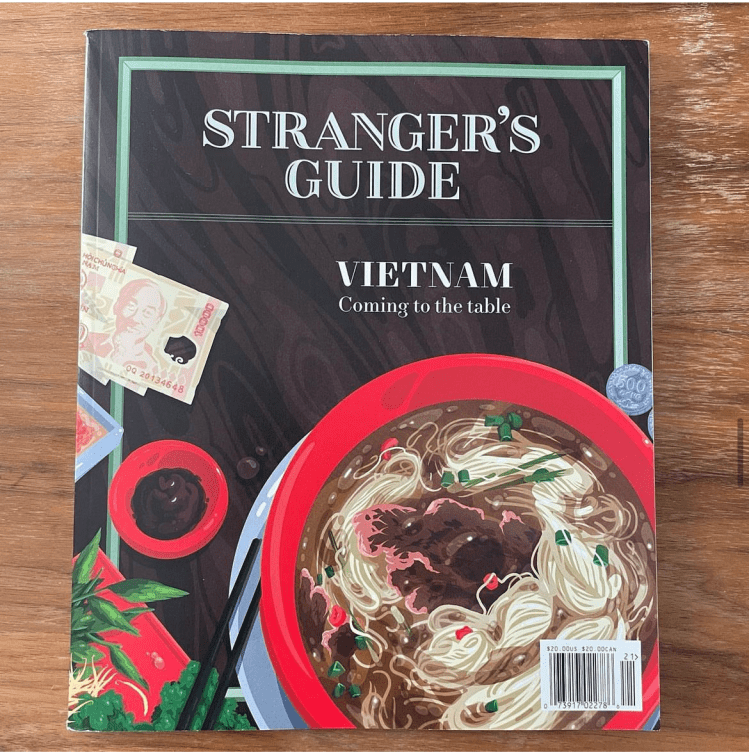

Instead of a book, I’m sharing a travel magazine today, though it isn’t a conventional one. In early March, Viet Nguyen announced that a selection of oral interviews concerning the memory of the war in Vietnam was set to appear in the next issue of the “Stranger’s Guide,” which itself is dedicated to Vietnam as a whole. These are transcripts excerpted from video interviews recorded by his students for a class of his. While the selection found at the end of the magazine are great, the “Stranger’s Guide: Vietnam – Coming to the Table” contains a wealth of other wonderful pieces as well, like poetry, fiction, photo essays, and articles. While I’m still reading through it, my favorite piece so far is a fascinating essay (translated into English) on the state of Phở in Vietnam today – though this one is probably best left to read after iftar. Ramadan 18

Ramadan 19

Here is one of my latest book acquisitions, Harsha Walia’s “Border & Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism.” My thanks to Maheen Zaman for the recommendation. While I have yet to begin reading it, I was immediately drawn to it given the author’s tackling of three interlocking issues that I’ve been engaging with through my current swath of readings and in-progress writing. I’ll also begin reading this imminently thanks to a much welcome reading group. Given how solitary the act of reading can be, having a community – as small as it is – with whom I can process a work is very much appreciated. Ramadan 19

Ramadan 20

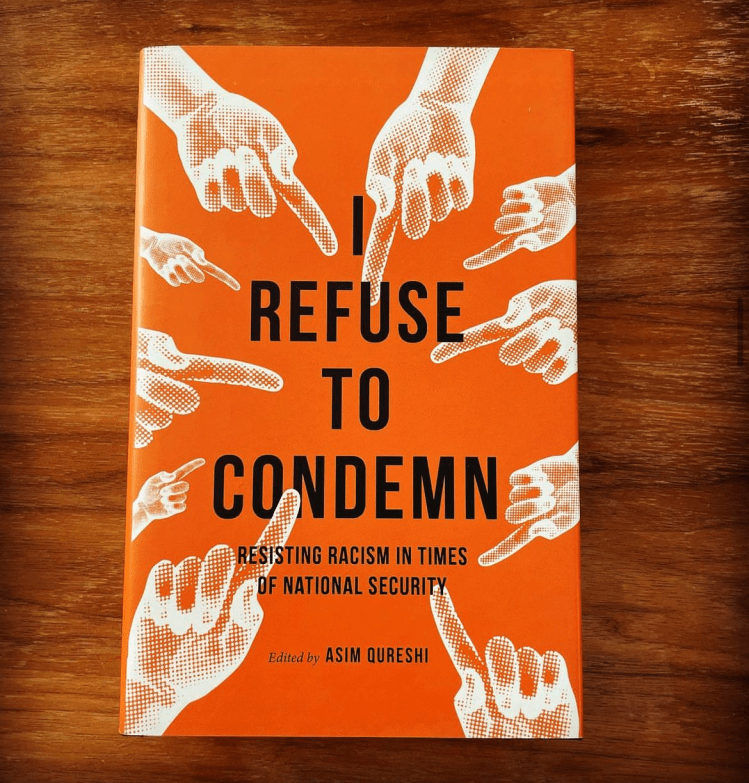

The book “I Refuse to Condemn: Resisting Racism in Times of National Security” was published in the UK and edited by writer and Research Director of CAGE Asim Qureshi, whose work was spotlighted in a past Ramadan book share. This volume brings him and numerous other activists and artists from across the anglophone world together to challenge the culture of condemnation that nationalist forms of supremacy foster. While the project was born out of Qureshi’s personal experience, the various voices contributing to the book offer a nuanced, multilayered, but mutually reinforcing set of critiques of the domesticating expectations of the security state. Personal narratives are joined by statistics and case studies to make for an convincing and compelling set of readings. It seems an apt follow up and complement to Qureshi’s previous book “A Virtue of Disobedience.” Ramadan 20

Ramadan 21

Below are two Qur’an related works. Both were gifted to me by a senior colleague and mentor. The tome on the left is a fairly obscure (at least to me) English translation entitled “The Qur’an: The Final Book of God.” It was translated by Daoud William S. Peachy and Maneh Hammad al-Johani and published in Saudi Arabia in 2012. I’m always interested in the justifications offered at the beginning of such works for why yet another translation and what sets this attempt apart. As many know, the reasons given came be quite uneven, though not in all cases. Next to it is a two-volume translation of selections from the famed Qur’an commentary by al-Tabari (d. 310/923). Entitled “Selections from the Comprehensive Exposition of the Interpretation of the Verses of the Qur’ān,” this substantial set was translated by Scott C. Lucas and published in 2017. Given how much attention was lavished on the translation of Tabari’s multivolume historical chronicle (published from 1989 to 2007 in 40 volumes), I’m somewhat surprised it took so long for even a selection of his exegesis to appear. Nevertheless, grateful to have added both to the shelves. Ramadan 21

Ramadan 22

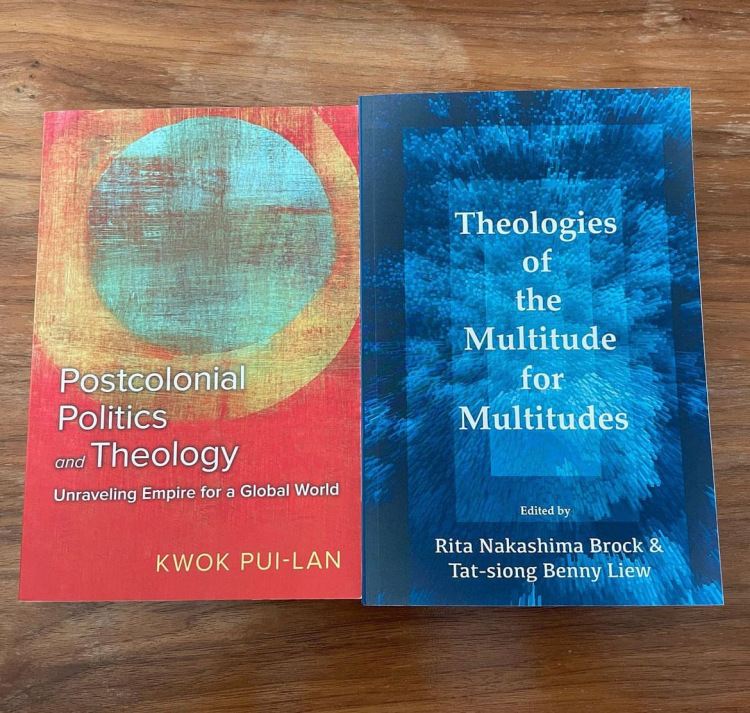

I’m featuring today two books connected to a theologian whose work has been formative for me and whose guidance and support have been invaluable. On the left is the latest book by Kwok Pui Lan, “Postcolonial Politics and Theology: Unraveling Empire for a Global Order,” which was published at the end of this past year. The book brings a critical comparative lens to political theology in order to decenter its predominant western forms in order to argue for a recovery and return to those historically marginalized ones of the Global South, with special attention paid to those representative of the Asian Pacific. This was one of my most eagerly anticipated books last year and it has been a pleasure reading through it. Next to it is a tribute volume made in honor of the author, “Theologies of the Multitude for the Multitudes: The Legacy of Kwok Pul-Lan.” It was also published late last year and I had the honor of contributing to it. While my work on this piece began before the pandemic lockdown, the self-reflection and writing that had gone into it proved one of my few life lines during those terrible early months. And, of course, many other fantastic pieces are to be found within this work as well. While this latter book was published in print by the Claremont School of Theology Press they have also very generously made it freely available to read electronically as well. Ramadan 22

Ramadan 23

The post today is less about the specific books and more about the series. Abu Hamid al-Ghazali’s (d.505/1111) Ihya ‘ulum al-din, or “The Revival of the Religious Sciences,” has long been regarded as an important spiritual classic. Although it is not an overly lengthy book when compared to more voluminous endeavors, the author divided his work into four parts of 10 books each. Over the past few decades we’ve seen modern English translations of select volumes appear sporadically, either from the Islamic Text Society or Fons Vitae. Since 2015, however, Fons Vitae seems to be making a concerted effort to translate the remainder of the work. Featured here are two of the more recent volumes to appear. The one on the left is Book 20 “The Book of Prophetic Ethics and the Courtesies of Living” translated by Adi Seta and the one on the right is Book 39 “The Book of Contemplation” translated by Muhammad Isa Waley. I’m glad to see more and more of this work made available to English-speaking readers and I’m looking forward to the series’ completion in the years ahead (isA). Ramadan 23

Ramadan 24

Published this year, “Menace to Empire: Anticolonial Solidarities and the Transpacific Origins of the US Security State” by Moon-Ho Jung has made it to my ever growing to-read pile. While my initial interest in this work lay with its coverage of Vietnam, which appears later in the book, I’m also quite interested in the author’s desire to draw together the wider colonial Pacific into the story of American Empire and race. In many ways, this seems like the natural, more in-depth follow-up to “How to Hide an Empire,” but with a sharper focus on those networks of Asian resistance. Ramadan 24

Ramadan 25

Antonio Gramsci was a noted Italian Marxist philosopher who was imprisoned in 1926 under Mussolini’s regime. Gramsci would remain there until his death in 1937. During his imprisonment, he spent much of his time writing, scrawling this thoughts down in two to three notebooks at a time. By the end of his life he had accumulated thirty-three notebooks covering a wide range of topics. Apparently, banker and economics scholar Raffaele Mattioli was a supporter of Gramsci and after the latter’s death, Mattioli took the notebooks and secured them in the vault of the Banca Commerciale Italiana, where he was the chief executive officer and then later chairman of the board. The notebooks remained in the bank vault for a year until they were able to be safely sent abroad. Years later, the same bank generously supported the English translation by Columbia University Press that you see here “Prison Notebooks: Volumes I-III.” The scholar responsible for compiling and editing this three-volume set that brings into English all of Gramsci’s notebooks is Joseph A. Buttigieg, whose family name might be familiar to many. Notably, Buttigieg lovely thanks his wife and son Peter in his “Acknowledgements.” Ramadan 25

Ramadan 26

I saw this new publication making the rounds on social media and felt compelled to acquire a copy given my work editing Sohaib’s book on preaching and my own writing on the spoken word. This is Khaled Abou El Fadl’s “The Prophet’s Pulpit: Commentaries on the State of Islam, Volume I,” which collects a selection of 22 Friday prayer sermons delivered by the author from January 2019 to March 2020. With the book having arrived just yesterday I haven’t had sufficient time to dive into the work. It’s appearance, though, reminds me how I wish more contemporary collections of Friday prayer sermons were available. It’s a religious discourse of immense significance that ought to have more attention than it presently does. As for this book, a quick perusal reveals an accessibility and urgency in the words shared here. Aimed at the American Muslim congregation rather than academia each piece is crafted and delivered to address the issues and challenges that confront our community today. I’m intrigued to see what lies within. Finally, if the “Volume I” in the subtitle is any indication, we can expect more to come on this front. Ramadan 26

Ramadan 27

At sunset yesterday the 27th of Ramadan entered upon us. It is among the nights that may well be Laylat al-Qadr, the Night of Power in which the Qur’an, God’s revelation to humankind, first descended upon the Prophet Muhammad. For this particular day I wanted to feature a special book. It felt right to make that work one crafted by many hands, one meant to extend love and care to many people, and one born out of faith and it’s challenges. This is “Mantle of Mercy: Islamic Chaplaincy in North America,” edited by a team of four: Muhammad A. Ali, Omer Bajwa, Sondos Kholaki, and Jaye Starr. My special thanks to Omer Bajwa who just recently signed this copy, though it may not be apparent from the picture. Gathered within this book’s pages are the words of many who have committed themselves to the call of Muslim chaplaincy. I am fortunate to know several of the writers within, though far from all. There are even two contributions by Sohaib Sultan, a chapter and an epilogue, submitted some time before his death just over a year ago. In fact, his pieces arise from his reflections on his imminent departure, serving simultaneously as a valuable tribute to him and as a trove of wisdom from him. Joining these pieces are thirty other valuable chapters born of discernment, insight, honest struggle, and practical guidance. Indeed the book as a whole marks yet another significant step in the development of an often overlooked discourse of faith leadership for our community, Muslim chaplaincy in its multi-faceted forms. May we make the most of these last days of this blessed month. Ramadan 27

Ramadan 28

The idea of the prophetic is central to the second part of my next work, although it remains only fragmentarily written. It is there that I try to build upon on two distinct, but not unrelated notions of the prophetic: the prophetic spirit disclosed in the Qur’an and through the example of our beloved Prophet as well as that which emerges out of the historical ground of America, especially as captured by the black experience. Of the latter, there is a long line to trace – one where Malcolm X figures prominently. While many have worked to surface this latter lineage, I feel especially indebted to the work of Cornel West, for whom the notion of the radical prophetic has figured consistently in his writings and words. I was reminded of this point when I picked up his “Prophetic Thought in Postmodern Times” at Bedlam Books in Worcester, Massachusetts. Published in 1993 as part of a two volume set (I picked up volume two not long after), the work reproduces speeches and talks delivered during that time period. What I found especially endearing is that the foreword was penned by his own parents reflecting on the man that their son had become over those past forty years. Reading this work now some two and a half decades later, it’s evident to me that West has been remarkably consistent in engaging these fiery ideas of pragmatism and prophecy in his long career. I witness it still in his writings and talks today. A passage from volume two “Prophetic Reflections: Notes on Race and Power in America” offers the following: “Prophetic Theology cuts much deeper than the intellect; Prophetic Theology forces us to exemplify in our own lives what we espouse in rhetoric. It raises questions of integrity, questions of character, and, most importantly, questions of risk and sacrifice” (223). Ramadan 28

Ramadan 29

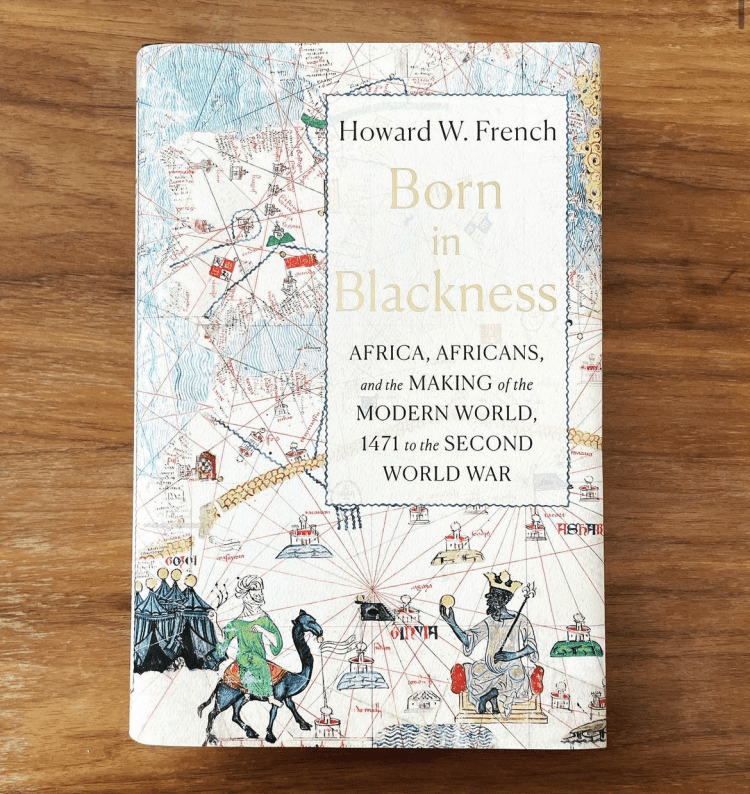

Here is another compellingly written book aimed at unsettling and reframing our understanding of history in a generative way. Howard W. French’s “Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War” seeks to recast the narrative of modern history by moving Africa from the periphery to the center. The work, for example, opens with an open ended account of the Muslim emperor of Mali, Abu Bakr II and his alleged voyage across the Atlantic using the tale to raise broader questions and thought-provoking speculations to frame the rest of the book. Wide-spanning in scope, but also adept at surfacing overlooked and subtle dynamics, the book has been a captivating tome – at least thus far. I’m especially looking forward to the fifth and final part of the book entitled “The Black Atlantic and a World Made New,” which brings the work halfway through the twentieth century. Ramadan 29

Ramadan 30

“Exterminate all the brutes!” are the words scrawled with finality by Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s novella “Heart of Darkness.” These same words mark the title of one of today’s books, Sven Lindqvist’s “‘Exterminate All the Brutes:’ One Man’s Odyssey into the Heart of Darkness and the Origins of European Genocide.” It is also the title taken by filmmaker Raoul Peck for his 2021 documentary miniseries on the European machinery of colonial inhumanity. It was while watching this series that I took note of several works that Peck references during the course of his gravely narration. Lindqvist’s book takes on the form of a personal travel narrative that is wrapped in history, philosophizing, and literary explorations (of Conrad especially) all in order to track the horrific genealogy of European imperialism and genocide. The other work “Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History” by Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot, is an astoundingly insightful book for its incisive critiques of history, archives, and the historical process as well as for its recasting of Haitian history and memorialization of Columbus through its interrogations of silences and novel juxtapositions. Peck’s documentary may be an accessible watch (though quite overwrought at times), but these books are profoundly more rewarding to work through. Ramadan 30

Eid al-Fitr

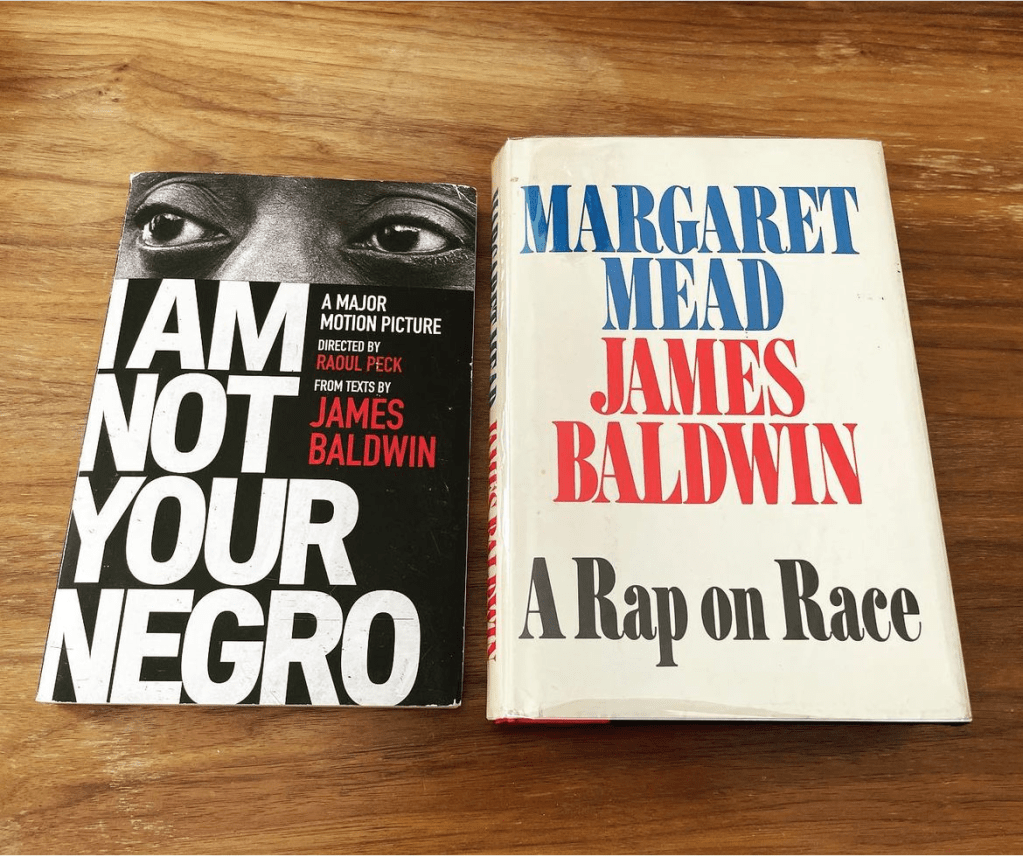

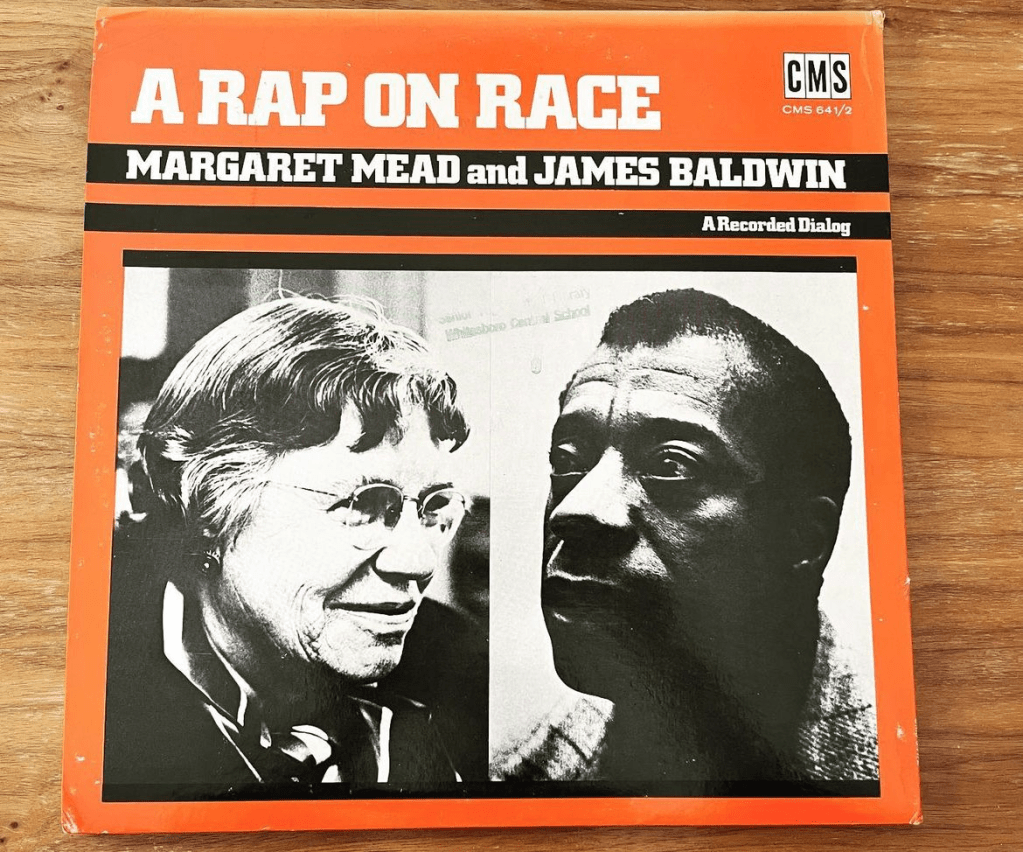

I wanted to end with a figure whose work has been deeply influential, despite the limited attention he’s been afforded in my Ramadan book share series, James Baldwin. The text on the left is a composite of sorts. “I Am Not Your Negro” was pulled together by filmmaker Raoul Peck in order to produce his 2016 Baldwin documentary by the same name. The Baldwin family had provided him with an incomplete manuscript entitled “Remember This House” that was intended to discuss America through the lives of his then-deceased (assassinated) friends: Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Medgar Evers. Baldwin himself died before completing his envisioned memoir. “I Am Not Your Negro” is Peck’s attempt to imagine what that work might have looked like had it been completed. Next to it is a relatively rare work entitled “A Rap on Race” from 1971. I first learned of it only after stumbling upon the double-vinyl album from 1972 featured in the other photo. I purchased the album right away despite not owning a record player (I’d do the same if I’d ever found vinyls with Malcolm X’s speeches). After some diligence and much patience, I was finally able to acquire the book you see here. According to the editor, “A Rap on Race” records the following: “Margaret Mead and James Baldwin met for the first time on the evening of August 25, 1970. They spent approximately one hour getting acquainted. On the following evening they sat down to discuss race and society. Their discussion was resumed the next morning and again that night. The entire conversation lasted approximately seven and one half hours. It was tape-recorded, and this book, ‘A Rap on Race,’ is the transcript made from those tapes” (i). Here are two important public intellectuals of their time, the anthropologist Margaret Mead and the renowned writer James Baldwin, engaging one another over one of the most critical matters of their era – a matter that continues to bedevil us to this day, the monstrosity of race. While today is indeed a day of celebration, we also should not forget the weight of the world rests no lighter today than on others. Eid Mubarak to you and yours. May God grant us strength and give us ease. Eid al-Fitr