For the fourth year of this series, I decided to finally dedicate the entire month (and then some) to a single theme, the life and legacy of Malcolm X, el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz. Every day of the month was set aside to feature at least one, though most days featured several, works on his life, words, and deeds. Back to the MRB.

Sha’ban 30-1

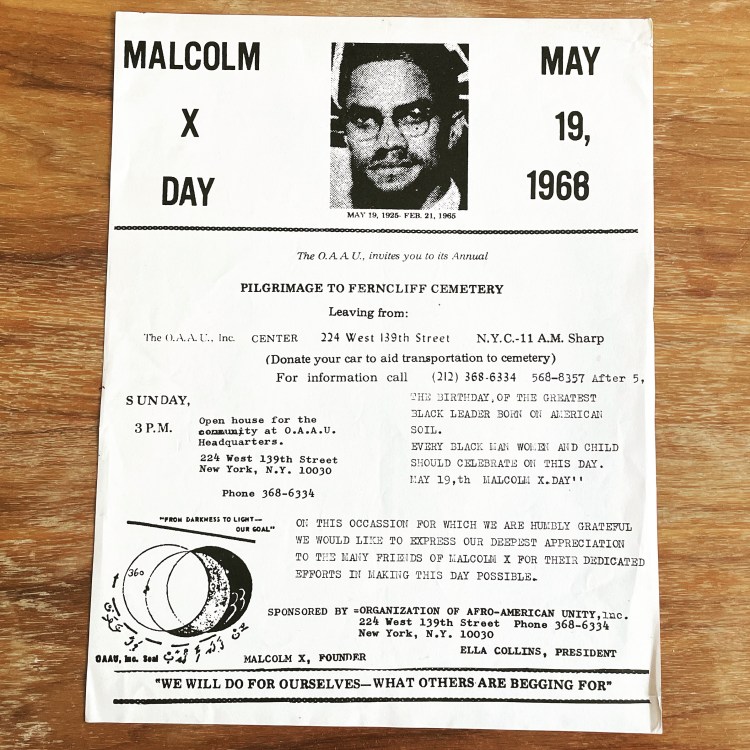

The month of Ramadan is set to begin with sunset today. I’ll be continuing my tradition of sharing at least one book a day insha’Allah. However, for this year, I’ve decided to finally make this month of bookshares united around a common theme, one I’ve had in mind for some time. As indicated by the flyer posted here, each book I share will come from my collection of works on Malcolm X el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz. A few caveats are in order. My collection is far from comprehensive so there will be works missing. Nor will I be able to share every work on my shelf that addresses the life and legacy of brother Malcolm, there are just too many for one month to contain. But I have endeavored to include as much as I can into the space I’ve allotted myself. There will be quite a few days with multiple works featured. In fact, today, the 30th of the Islamic month of Sha’ban will have two posts, this one and another. What I’m sharing here is a piece of ephemera, a flyer distributed by Malcolm’s Organization of Afro-American Unity in the lead up to Malcolm X Day on May 19, 1968. As the leaflet describes, community members were planning to gather in Harlem at the O.A.A.U.’s headquarters at that time to then embark upon a northward pilgrimage to Ferncliff Cemetery where Malcolm was laid to rest just 3 years earlier. Rather than commemorating his death, the date chosen is Malcolm X’s date of birth. While I am unsure if the pilgrimage has run continuously since his death (it may very well have), I have had the honor of joining it when it overlapped with Ramadan a few years ago. Sha’ban 30, the first of two

Sha’ban 30-2

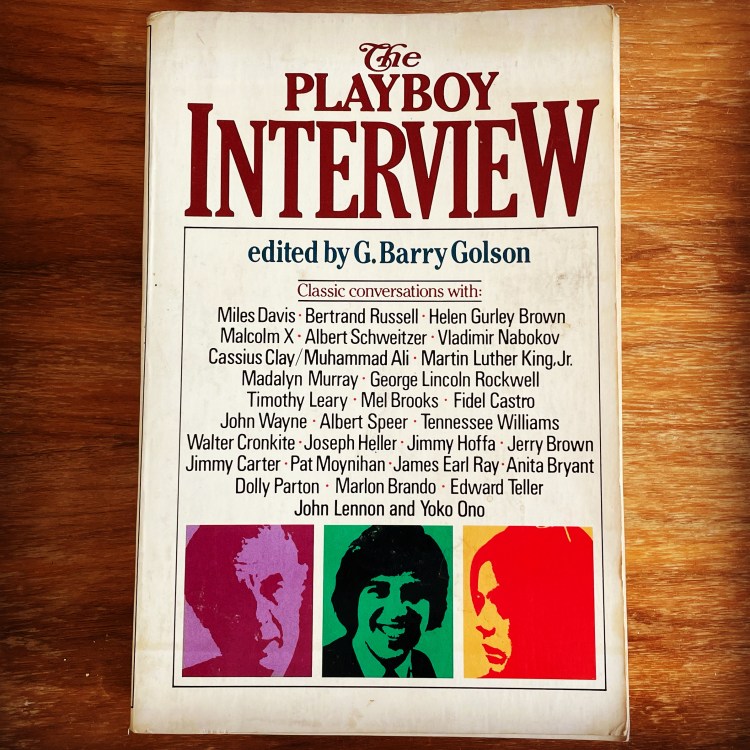

This may seem like an unconventional book to feature, but “The Playboy Interview” (1981) edited by G. Barry Golson collects an impressive number of substantive and serious interviews printed in the magazine’s pages. In May 1963, journalist Alex Haley’s in-depth interview with Malcolm X was first published, contained here on pages 37-53. The reaction to the piece was strong. As the editor notes: “The publication of the interview produced an avalanche of mail… A Doubleday editor was sufficiently impressed with the interview to propose to Haley that it might be the basis of a book about Malcolm. Although Doubleday later withdrew, and Grove Press became the publisher, Haley’s collaboration with Malcolm was an immense success under the title ‘The Autobiography of Malcolm X’… In February 1965, a week before the book galleys from Grove Press were due to Haley’s desk, Malcolm X was assassinated” (38). Without this interview, we may never have benefited from that book, which went on to radically change the minds and lives of innumerable others, myself included. Alongside the Malcolm X piece are interviews with other luminaries like Miles Davis, Muhammad Ali, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Sha’ban 30, the second of two

Ramadan 1

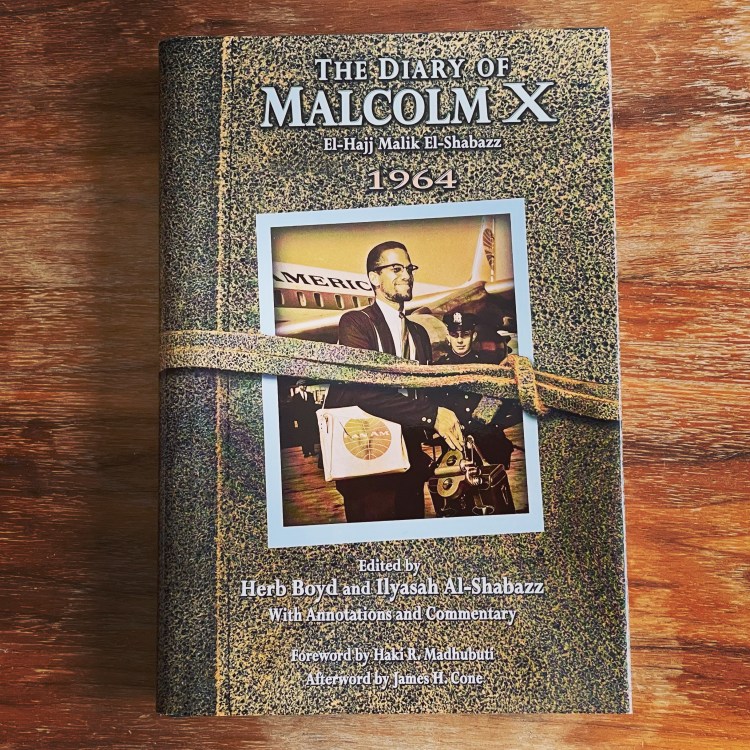

Ramadan Mubarak. To begin this month, I am sharing a publication that reproduces Malcolm X’s diary in which he captured his experiences while traveling from April 15th to November 17th in 1964. This was an especially important time in Malcolm’s life. He had broken with the Nation of Islam prior and just three months after the diary concludes he would be assassinated. While the diary has endured as an artifact for many decades, it was not until 2013 that Herbert Boyd and Malcolm X’s daughter Ilyasah Al-Shabazz edited and published it as “The Diary of Malcolm X (El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) 1964.” In the Epilogue Ilyasah shares the following: “As we read Malcolm’s Diary, we gain greater insight into the courage and commitment required to leave the land of his ancestors, refuse refuge for himself and his family, and return to the United States with the knowledge that enemies committed to his destruction lie in wait. An invaluable gift of these pages for me is the incomparable lesson of faith. My father remained faithful to the very end” (184). Having just completed my own first ‘Umrah or visitation to the Kaaba, I wanted to share the following excerpt from Malcolm X’s diary on Saturday, April 18th, 1964 during his Hajj pilgrimage: “Carrying my slippers, I followed the Mutawwif [guide]. Then it was that I saw the Kaaba, a huge stone house in the middle of the Great Mosque. It was being circumambulated by thousands of praying pilgrims (all sexes, sizes, colors) who were making the 7 times. The Mutawwif led me around 7 times, fighting my way with the praying crowd chanting pilgrims. It was a sight to witness. Many had waited a lifetime to come & had spent their life’s savings to pray & to give praise in the House of God. The 7th time around I made two rakas [Raka’at]. As I prostrated to the floor of the Great Mosque, the Mutawwif & my companion had to keep the crowd from trampling me. We then drank from the Well of ZamZam and then traversed between the Hill of Safar [sic] & Marwa, where Hagar’s feet tread thousands of years earlier. This whole area is being covered by the new mosque that is being built” (12). Ramadan 1

Ramadan 2

The two books featured today were published during Malcolm X’s lifetime in contrast to the innumerable works, including the Autobiography, that have appeared since his death. The first book “When the Word is Given…: A Report on Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, and the Black Muslim World” appeared in 1963 from journalist Louis Lomax (d. 1970). Lomax became the first African-American television journalist in 1958 and then collaborated with Mike Wallace in 1959 to produce the TV documentary “The Hate that Hate Produced,” which brought the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, and Malcolm X into focus for white America at a national level. This book not only contains Lomax’s analysis and observations but also captures many of Malcolm’s speeches for the first time in the work’s Part Two. Additionally, the book contains many compelling and worthwhile photos of the NOI and Malcolm from the era. At the work’s end, Lomax concludes with an interview with Malcolm X. The other book, “The Black Muslims in America,” published earlier in 1961, was authored by African American scholar and sociologist C. Eric Lincoln (d. 2000). At the time, his book was the first scholarly study of the Nation of Islam linking it with earlier black nationalist movements. In his treatment of the NOI, Lincoln also makes more than ample mention of Malcolm X and his role in it. Notably, both works refer to members of the Nation as “Black Muslims” in contradistinction to “Muslims” despite the Nation’s insistence against such qualifications. Ramadan 2

Ramadan 3

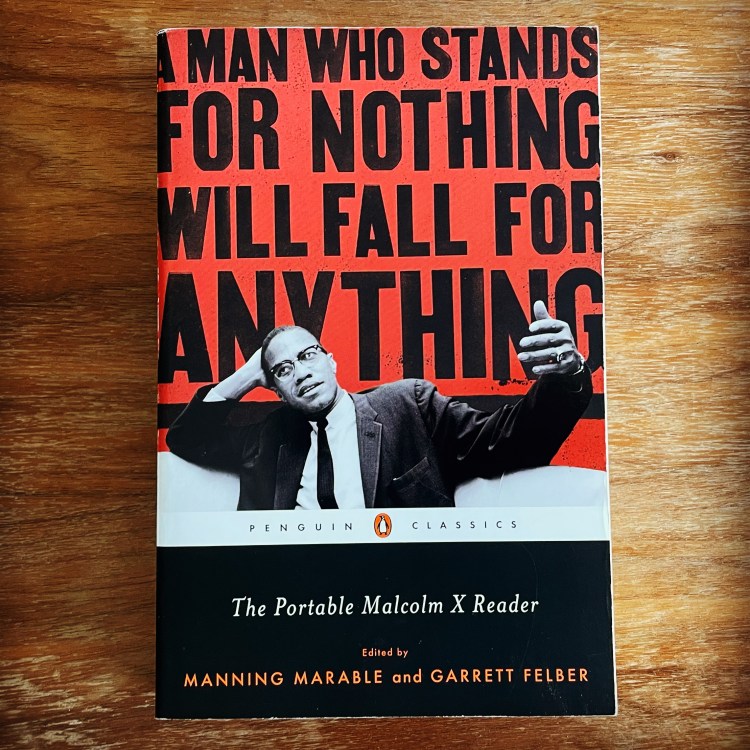

Published more recently in 2013, the Penguin Classic “The Portable Malcolm X Reader” edited by Manning Marable and Garrett Felber collects a diverse assortment of materials around the life of Malcolm. While abounding in newspaper reports, magazine articles, and transcripts it also contains court records and excerpts from Malcolm’s FBI file. At its end are compelling oral histories and reflective retrospective pieces written by notable voices like James Baldwin, Eldridge Cleaver, and Robin D.G. Kelley. There are many noteworthy pieces within the volume, but I found especially interesting George Plimpton’s article from Harper’s Magazine “Miami Notebook: Cassius Clay and Malcolm X” from June 1964, the four pieces documenting Malcolm’s travels to the Middle East in 1959 (well before his break with the NOI and his own Hajj pilgrimage), and the early documents concerning his family. In the Pittsburgh Courier, August 15, 1959 Malcolm X wrote from Saudi Arabia: “I am leaving Arabia without visiting the Holy City, Mecca; an experience which would break the average Moslem’s heart; but if it is Allah’s will, I shall return with Mr. Elijah Muhammad, spiritual head of the American Moslems when he comes to this area during the fall” (140). By the will of God, Malcolm would return to visit Mecca four years later in 1964 under very different circumstances and with a radically different sense of self. Ramadan 3

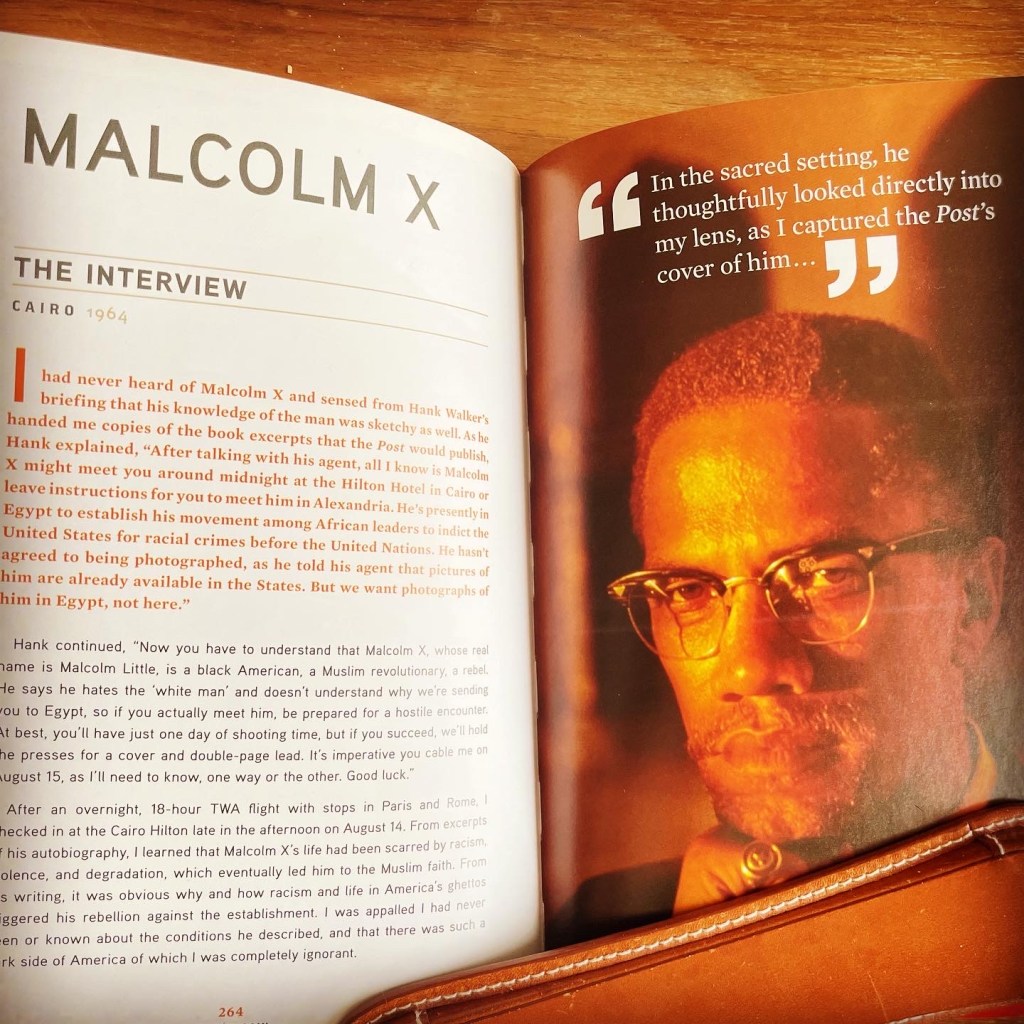

Ramadan 4

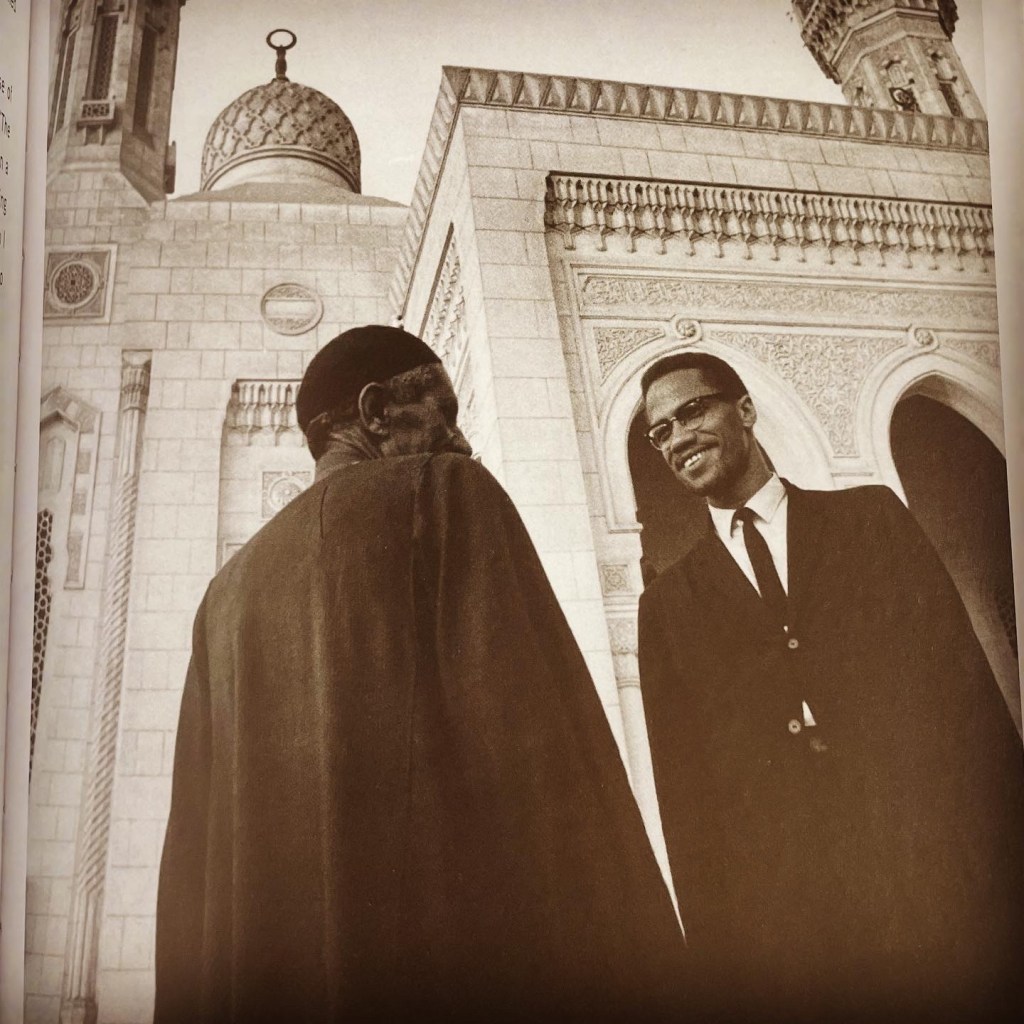

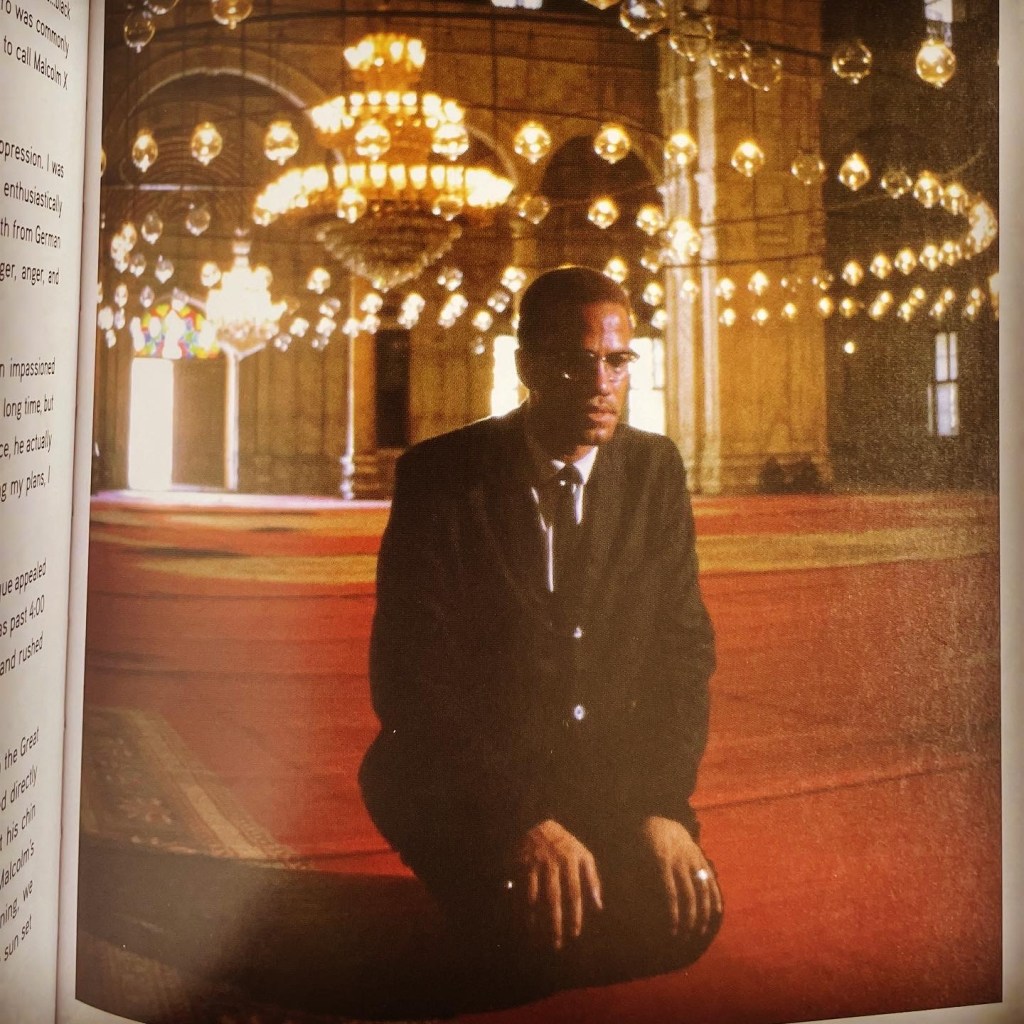

I am not usually keen on collecting the works of photojournalists, but when I realized that some of the most iconic photographs of Malcolm X from his Cairo visit in 1964 were taken by John Launois I immediately looked to see if a book collecting his photographic work existed. I was pleased to discover this work “L’Americain: A Photojournalist’s Life” (2013) by John Launois with Chris Pan Launois. The section on Malcolm X is admittedly briefly, only 8 pages out of more 400 in total, but the book reproduces those iconic images and offers Launois’s very personal reminiscence of his photoshoot and encounter with Malcolm X. From the book: “I asked Malcolm X, ‘How could America liberate Western Europe, yet simultaneously oppress you and your people?’ I wanted to know. ‘That’s a very long and complex story,’ he said, as he intelligently and articulately gave me a short course on black history in America…I could have listened to him all night. I had many questions to ask, but he had a letter that he wanted me to personally deliver to his wife Betty Shabazz in Queens, New York. We met for the last time the next morning. He gave me his letter fully addressed and again asked me to deliver it in person, saying, ‘Don’t mail it. I don’t trust the mail, but I trust you…’ Malcolm X and I shook hands just before I left for the airport, and our eyes met and held. We had spent 16 hours together, and it seemed we mutually understood our personal rebellions and had empathized briefly with one another. His struggle for the rights of ‘his people’ made my own search for a more egalitarian society seem insignificant, the privilege of a free white man. As my driver pulled away, we waved goodbye. Little did I know I would never see Malcolm X again…” (270-2). Ramadan 4

Ramadan 5

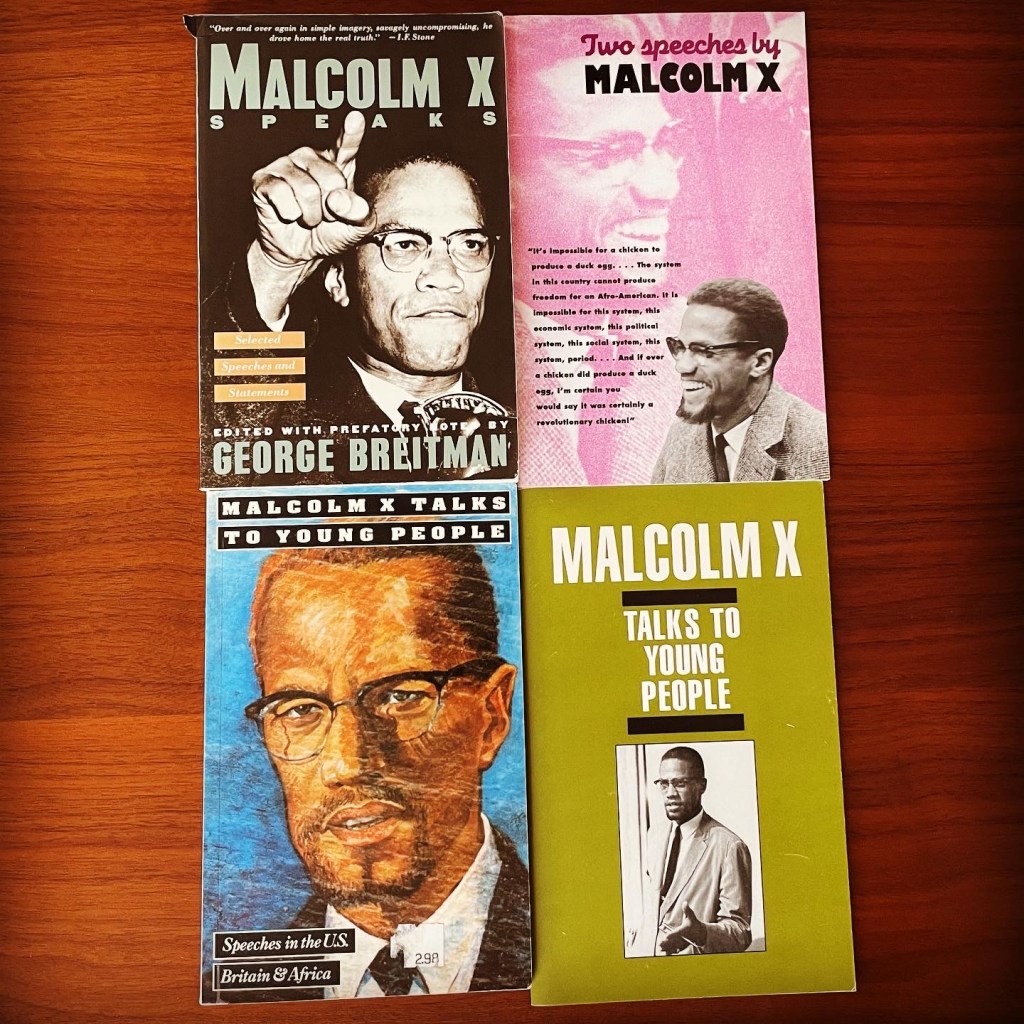

I could easily spend at least a week documenting the many volumes collecting the speeches of Malcolm X. I’ve decided to gather the ones I have all into one post in order to make room for the many other sort of works out there. Shown here are: “Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements” (1965) edited by George Breitman, which gathers speeches from 1963-65; “Two Speeches by Malcolm X” (2011, third ed. 1990), which actually contains several more pieces than the title promises, including a January 1965 radio interview; “Malcolm X Talks to Young People: Speeches in the U.S., Britain, and Africa” (1993, orig. 1991), focusing on speeches from his late travels; “Malcolm X Talks to Young People” (2007) reproduces the last 3 pieces from the preceding work; “The End of White World Supremacy: Four Speeches” (2020, orig. 1971), edited by Benjamin Karim, which provides links to the audio for two of the speeches; “Malcolm X: Speeches at Harvard” (1991), edited by Archie Epps, which contains a hundred page introduction and Malcolm’s two speeches at Harvard University from March 1959 and March 1964, as well as a final speech at Harvard Law School in December 1964; “Malcolm X: The Last Speeches” (1989), edited by Bruce Perry, which also collects speeches from 1963-65; and “February 1965: The Final Speeches” (1992), edited by Steve Clark, which provides an extensive collection of interviews, remarks, reports, and speeches from February 3 to 19, 1965. I’ll conclude with the closing words of Malcolm to Gordon Parks in an interview conducted on Feb. 19: “‘That was a bad scene, brother. The sickness and madness of those days – I’m glad to be free of them. It’s a time for martyrs now. And if I’m to be one of them, it will be in the cause of brotherhood. That’s the only thing that can save this country. I’ve learned it the hard way – but I’ve learned it. And that’s the significant thing.’ As we parted he laid his hand on my shoulder, looked into my eyes and said, ‘As-salaam-alaikum, brother.'” (232). Ramadan 5

Ramadan 6

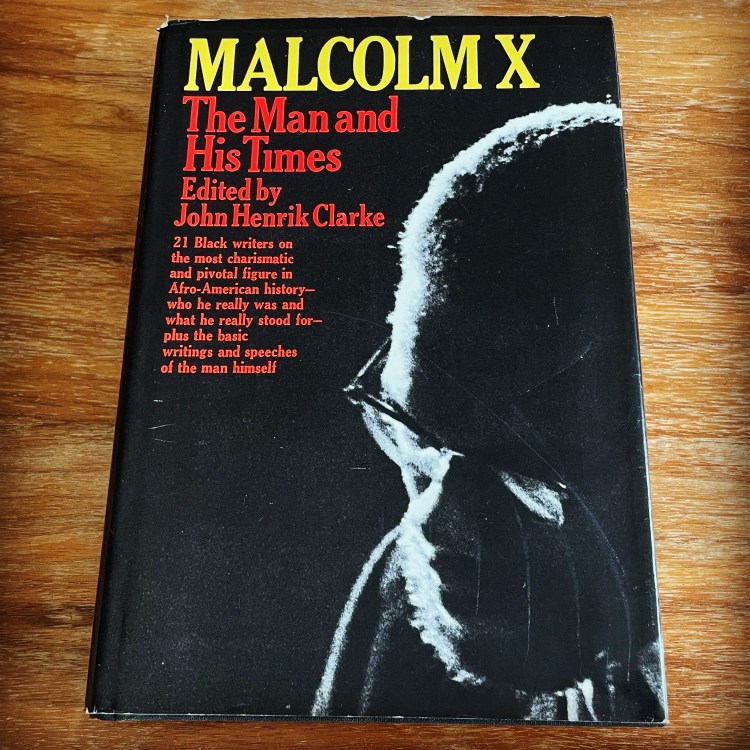

As far as I can tell, “Malcolm X: The Man and His Times” (1969) is the earliest tribute collection to appear after Malcolm’s death. The volume was compiled by John Henrik Clarke, the famous African-American historian who helped pioneer Africana studies in the United States. In its pages, space is given to a host of black voices like Betty Shabazz, Reverend Albert Cleage, and Ossie Davis. In addition to such essays, Clarke also includes several of Malcolm’s speeches as well as a transcript of a conversation he had with two FBI agents when they visited his home (Malcolm had a tape recorder set up under his couch in advance). Near the end, Clarke includes the draft petition that Malcolm wanted to bring before the United Nations charging the United States of genocide against its black population (343-351). Then A. Peter Bailey (who I’ll return to later) ends the book with a “A Selected Bibliography,” documenting much of what had appeared in the 4 years since Malcolm’s death (and prior). In many ways, it’s significant first step in delineating the contours for future Malcolm X scholarship. I’ll end with an excerpt from “Islam as a Pastoral in the Life of Malcolm X” by Abdelwahab M. Elmessiri, an Egyptian who was completing his PhD in English at Rutgers. “The pastoral ideal is used by the revolutionary or visionary writer to undercut and expose a complex yet stagnant status quo. He may not believe that such an ideal actually exists, yet he believes in the possibility of vision and its superiority over fact and reality. In this sense the pastoral mode is as inevitable as history and revolution. Islam, for Malcolm, was such a pastoral… The Islamic-Arab world, in spite of all its historical tensions, provided Malcolm with a pastoral vision of a world morally superior to America, at least insofar as human and racial relationships are concerned. By returning to America to realize his new vision through social action, Malcolm showed that he belonged to the tradition of historical revolutionaries who want to alter reality, not by transcending or breaking away from it, but by reshaping it according to their vision of the ‘good life'” (69-70). Ramadan 6

Ramadan 7

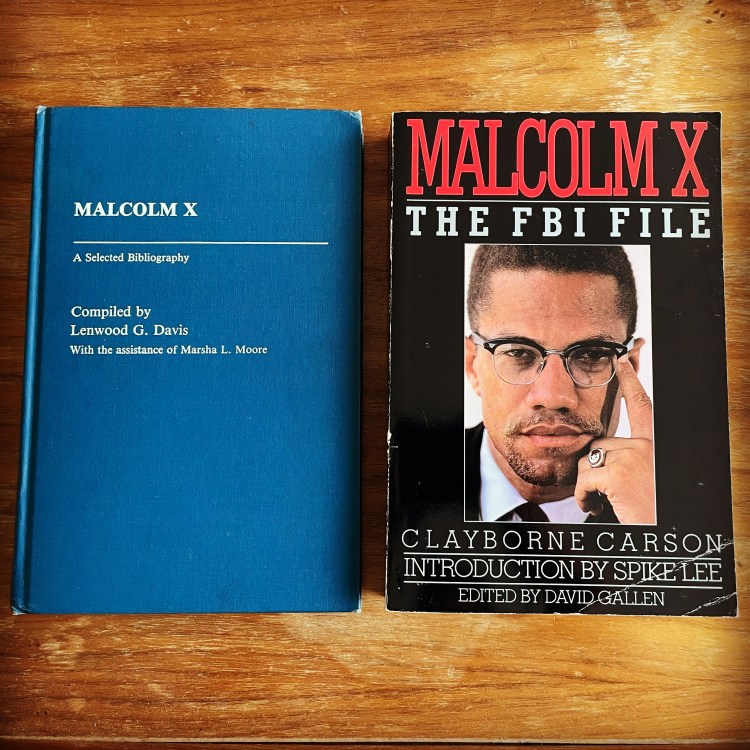

In the previous book spotlight, I mentioned the relatively brief bibliography composed by A. Peter Bailey in 1969. In 1984, Lenwood G. Davis and Marsha L. Moore compiled a new one, substantially expanded to account for the intervening years, in a book-length work entitled “Malcolm X: A Selected Bibliography.” Over 1100 items are documented in total and it is worth perusing the lists of works detailed therein. While an important work for what it gathered at that time, there’s not much to share here other than bibliographic entries, so I’ve also included alongside it “Malcolm X: The FBI File” (1991) which was composed by Clayborne Carson and edited by David Gallen. While Carson is renown for his extensive scholarship on Dr. King, his work here on Malcolm is appreciated. In this tome of over 500 pages, Carson has reproduced the manifold, often sterile, and heavily redacted reports made by FBI agents surveilling Malcolm X and his activities. Names of agents and informants and other identifying details have been diligently censored prior to Carson’s access. The reports begin on May 4, 1953 and extend to February 23, 1967 to document the court trials of the Malcolm’s alleged assassins. Carson helpfully divides the largely chronological reports into sections offering brief summary descriptions at the beginning of each. A final section reaches from 1969 to 1980 to include the FBI’s review of books on Malcolm as well as its surveillance of the posthumous celebrations of Malcolm’s birthday. There is a flurry of FBI reports that were submitted in the days after Malcolm’s murder, but given their grimness, I’ll share instead the brief FBI report from 1959 concerning Malcolm’s travel to Egypt: “On 7/13/59 [BUREAU DELETION] advised that he learned from a member of NOI, NYC that MALCOLM X LITTLE was in Africa and had an audience with NASSER of Egypt. This audience was to set up meeting between NASSER and ELIJAH MUHAMMAD. [BUREAU DELETED] didn’t know source of member’s info” (159). A sample of our surveillance state at work. Ramadan 7

Ramadan 8

David Gallen, who helped edit the “Malcolm X: The FBI Files” (1991) edited three other works featured here. First is a memoir from Benjamin Karim, who served as Malcolm’s assistant in Harlem for seven years. “Remembering Malcolm: The Story of Malcolm X from Inside the Muslim Mosque” (1992), was co-written by Karim and Peter Skutches with Gallen’s help. The book tacks back and forth between the known contours of Malcolm’s life with the reminiscences from Karim. Near the end of the book Karim writes “His people were his mission. We were the reason Malcolm came back from Africa… His friends there had feared for Malcolm’s life in America. They had tried to persuade him not to return to the United States. They had offered him a home there and the Ethiopian government had promised him sanctuary. Malcolm loved Ethiopia, but, he said, his mission did not lie there. It lay here, among us.” (182). Gallen also compiled the tribute “Malcolm X: As They Knew Him” (1992) that contains a long essay by Gallen and Skutches, interviews with Malcolm, and reprinted reflections from figures like Alex Haley, James Baldwin, and Eldridge Cleaver. Finally, Gallen edited “A Malcolm X Reader: Perspectives on the Man and the Myths” (1994), which excerpts passages from other works including Karim’s memoir, the Autobiography, James Cone’s “Malcolm and Martin and America,” as well as an interview between Gallen and Alex Haley. From that interview: DAVID GALLEN: What character traits in other people were most important to Malcolm? ALEX HALEY: The first thing that comes to mind is punctuality. I don’t know anybody who was so time-conscious as Malcolm. If you had an appointment with him at ten o’clock or two o’clock or six o’clock or whenever, please be there at that time. He had a kind of out-of-the-ordinary, almost hyper responses to people who were late. If you were late, you were exhibiting a whole lot of negative things in his view: that you were not to be trusted; that you did not really care seriously; that you were not serious at all.” (218) Ramadan 8

Ramadan 9

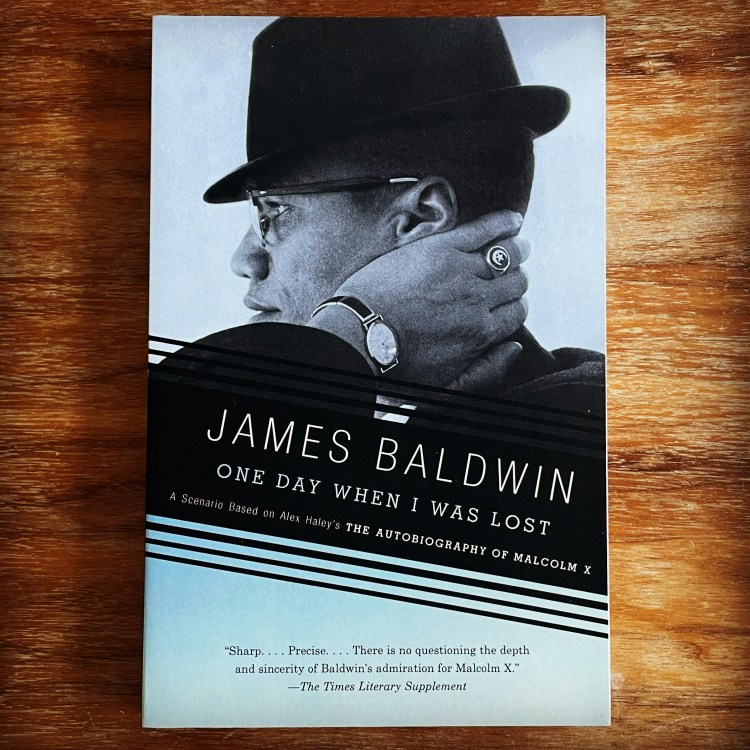

In 1968 James Baldwin began working on a screenplay based on “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” to be the basis of a Hollywood movie. What resulted was “One Day When I Was Lost” (1972), but it was far from an easy undertaking for Baldwin and a film would never emerge from his efforts during his lifetime. Warner Brothers buried it, so Baldwin published his script independently. In fact, when Baldwin reflected upon the literary enterprise he wrote “I would rather be horsewhipped, or incarcerated in the forthright bedlam of Bellevue, than repeat the adventure” (“The Devil Finds Work,” ). Baldwin’s script would be used later as the basis of Spike Lee’s efforts, but because of substantial changes made to that original work, the Baldwin Estate (James Baldwin had passed away in 1986) requested that Baldwin’s name be removed from the credits entirely. The journey to the Audubon Ballroom, where Malcolm would breathe his last, serve as bookends to the film with the opening scene and the penultimate one set around it. The second scene, however, is with Malcolm abroad: “(A very young black STUDENT, male, with a bright and eager face, is speaking to him.)

STUDENT: You must return. You must come back to us.

MALCOLM: I have come back. After many centuries. Thank you- thank you!- for welcoming me. You have given me a new name!

(Malcolm, in a great hall, somewhere in Africa, being draped in an African robe. The black ruler, who places this robe on him, pronounces this new name at the same time that MALCOLM repeats it to the STUDENT.)

MALCOLM: Omowale.

STUDENT: It means: the son who has returned.

MALCOLM: I have had so many names-

(We see the Book of the Holy Register of True Muslims. A hand inscribes in this book the name: El-Haji Malik El Shabazz. We see a family Bible and a black hand inscribing: Malcolm Little, May 19, 1925.)” (7). Ramadan 9

Ramadan 10

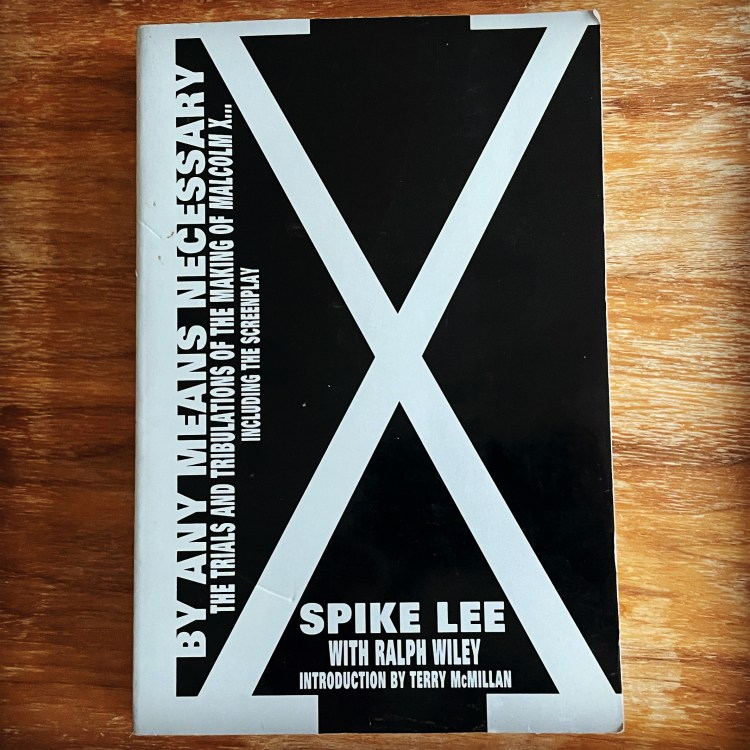

In 1992 director Spike Lee released his critically acclaimed film “Malcolm X” from Warner Bros. In the years leading up to the movie’s debut, the memory of Malcolm X had been undergoing a cultural revival. The keen-eyed reader of this Ramadan series will note that many of the publications were published in the late 80s/early 90s as part of this moment of rediscovery. Lee’s film was part of this resurgence and certainly helped fuel it further. However, the making of the film was far from easy. Protests and controversies followed the film’s development, production, and funding. Spike Lee criticized a white director, Norman Jewison, being attached to the project. Then, when the project came to him, Lee was targeted as a poor choice by some Black critics, Amiri Baraka being the one of the most outspoken. Spike Lee, with Ralph Wiley, documents that tumultuous experience from a personal vantage in “By Any Means Necessary: The Trials and Tribulations of the Making of Malcolm X” (1992). Concerning the movie, Spike Lee writes: “My desire, my prayer is for this film to show how a man or a woman can evolve even when the worse things happen to you, even when you’ve been taught to hate. When everything in your life has taught you to hate. You can still evolve, you know. That’s my desire, to reflect that in this role” (116). On Malcolm, Lee reports the following from an interview with Benjamin Karim: “He [Malcolm] was a fanatic for education. He once said that the Black college student would be very instrumental in the liberation of Black people. He would always try and surround himself with people who had academic knowledge. He had great respect for it. That’s why he sorta liked James Baldwin. Malcolm knew Baldwin was an intellectual, but he also knew Baldwin wasn’t brainwashed” (36). The book ends with the complete screenplay of the film, which actually lists James Baldwin as one of its authors alongside Arnold Perl and Spike Lee (despite what I said about the film credits previously). As a final note, “Malcolm X” was also the first American feature film (rather than a documentary) to be granted permission to film in Mecca. Ramadan 10

Ramadan 11

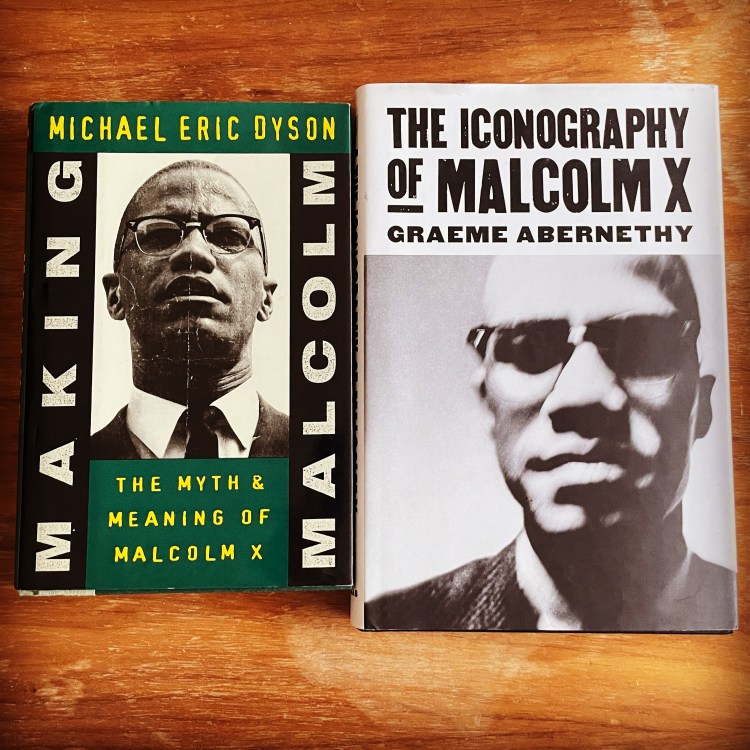

In 1995, Michael Eric Dyson published “Making Malcolm: The Myth & Meaning of Malcolm X” after witnessing the “cultural rebirth” of Malcolm X in the preceding years. Dyson critically assesses the ways that Black media, art, and consumerism have tried to revive and reshape Malcolm and his legacy, while also attending to the larger social world at work and its ills. While the work might seen dated in parts by this point, Dyson offers keen readings that remain relevant to our own times. “Malcolm’s defiant expression of black rage has won him a new hearing among a generation of black youth whose embattled social status due to a brutally resurgent racism makes them sympathetic to his fiery, often angry rhetoric. Malcolm’s take-no-prisoners approach to racial crisis appeals to young blacks disaffected from white society and alienated from older black generations whose contained style of revolt owes more to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s nonviolent philosophy than to Malcolm’s advocacy of self-defense” (87). More recent is Graeme Abernethy’s “The Iconography of Malcolm X” (2013). As the title indicates, Abernathy’s focus is on the history of the “icon” of Malcolm X and how his variously imagined image has been deployed and interpreted. Taking a historic approach, the author begins with the images of Malcolm that were in circulation during his lifetime, before than turning to the Autobiography. The book then examines how Malcolm was envisioned from 1965-1980 and then 1980 to the present, clocking along the way the significance of Spike Lee’s film, the music industry, and an array of other artistic portrayals and media inclusions. “Malcolm was well aware of the ideological efficacy of image making, frequently insisting upon the central role of the circulation of distorted images of Africa in fabricating the inhumanity of persons of African descent. His theoretical grasp of what he termed in a late speech ‘the science of imagery’ enabled him both to analyze the role of representation in ideological (and, indeed, psychological) control and to exploit his own image in the interests of black empowerment” (4). Ramadan 11

Ramadan 12

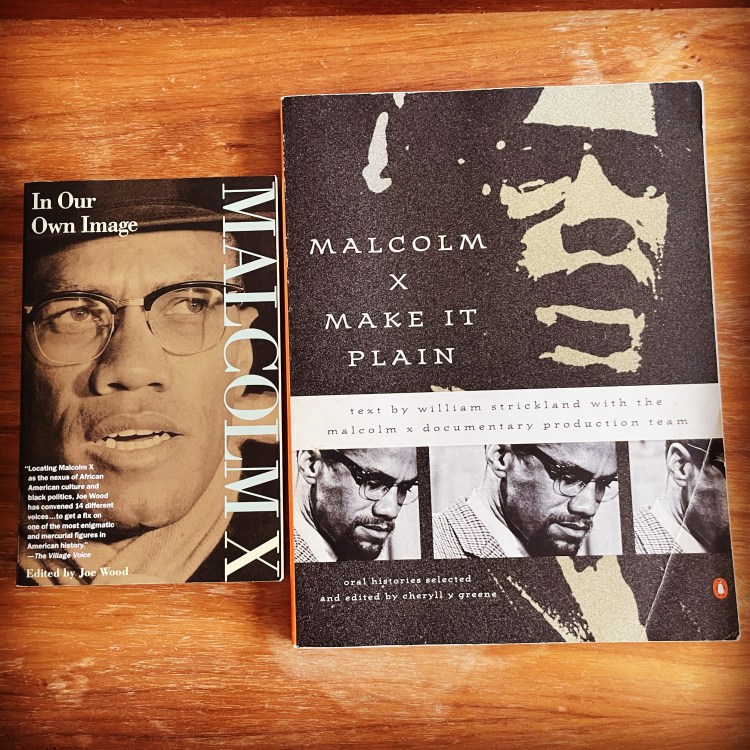

In many ways the first book, “Malcolm X: In Our Own Image” (1992) should have been part of the previous day for its critical work in establishing what some have called Malcolm X studies. Being an edited volume, however, I saved it for today to share alongside another compelling collection. The editor Joe Wood, brings together an impressive range of Black scholars to weigh in on the significance of Malcolm X including Angela Davis, Cornel West, Adolph Reed, Jr., and Robin D.G. Kelley. Describing his efforts, Wood writes, “This book is Black thinking on the subject of Malcolm X; it is brothers and sisters talking. I’ve invited some of our thinkers to critique Malcolm X and to make sense of Malcolm X’s currency among us, and to make sense of Blackness itself – its meaning today and its usefulness as a concept to African America. We speak because we dare to look in the mirror and see our heroes and ourselves; we speak because Blackness has come to mean so many things, and nothing; we speak because we seek to name ourselves, and our lives” (3). Next to it is “Malcolm X: Make It Plain” (1994) with text by William Strickland and oral histories selected by Cheryll Y. Greene. While an impressive work on its own, this book is intended as a companion to the 1994 PBS documentary film by the same name. Strickland offers a narrative through the life of Malcolm X that is generously accompanied with images from those times, while Greene weaves into the work oral histories shared by those that lived alongside Malcolm X bringing the work even more to life. From his half-sister Ella Collins, “I thought the Hajj would tie him down. Give him a walking stick so he could guide more carefully. Wake him up. Talk to him. Seek him out and bring him out of the field and put him in a role and let him hold his own” (177). From Maya Angelou during her time in Accra, Ghana, “It was heady, intoxicating, and into this boiling brew came Malcolm. Well, he was the man for the time. He was as large as the time. He wove such magic, and he dressed all of us in this rich fabric of his intelligence and insight” (179). Ramadan 12

Ramadan 13

In 2020, the documentary “Who Killed Malcolm X?” prompted the Manhattan district attorney’s office to review the investigation of Malcolm’s murder, which eventually lead to the exoneration of Muhammad Aziz (Norman 3X Butler) and Khalil Islam (Thomas 15X Johnson) the following year. That series, however, is simply one of the most recent iterations of works exploring and speculating on the murder of Malcolm X and the full extent of the planning behind the assassination. In 1976 George Breitman, Herman Porter, and Baxter Smith published “The Assassination of Malcolm X,” which seems to be the earliest book dedicated to the task. It collects Porter’s account of the trial as well as Breitman’s take on Malcolm and his ideas (all of which are reprints). Smith’s sole contribution is a reprint of an article of his that tries to draw the FBI into the conspiratorial web by pointing to its history of surveilling and disrupting Black movements at the time. In 1992 Michael Friedly published “Malcolm X: The Assassination” where he explicitly interrogates the “conspiracy theories” abounding around Malcolm’s death, ultimately dismissing government involvement and arguing instead for the Nation of Islam’s role. He also discusses the wrongful convictions of Butler and Johnson naming instead four members of the Nation of Islam in Newark – a move that would be later be repeated much later and with far greater attention by Les Payne in his biography of Malcolm X (featured later this month isA). In contrast to Friedly’s work is the book written by Karl Evanzz “The Judas Factor: The Plot to Kill Malcolm X” (1992) that appeared the very same year and very much in the wake of Spike Lee’s film. Moving in the opposite direction than Friedly, Evanzz casts a wide international net aimed at pulling in both the FBI and CIA into the conspiracy to assassinate Malcolm X. While our knowledge about Malcolm’s death today has developed significantly since these works, they all remain interesting for what they reveal about the trajectories of thought at work during these times. Ramadan 13

Ramadan 14

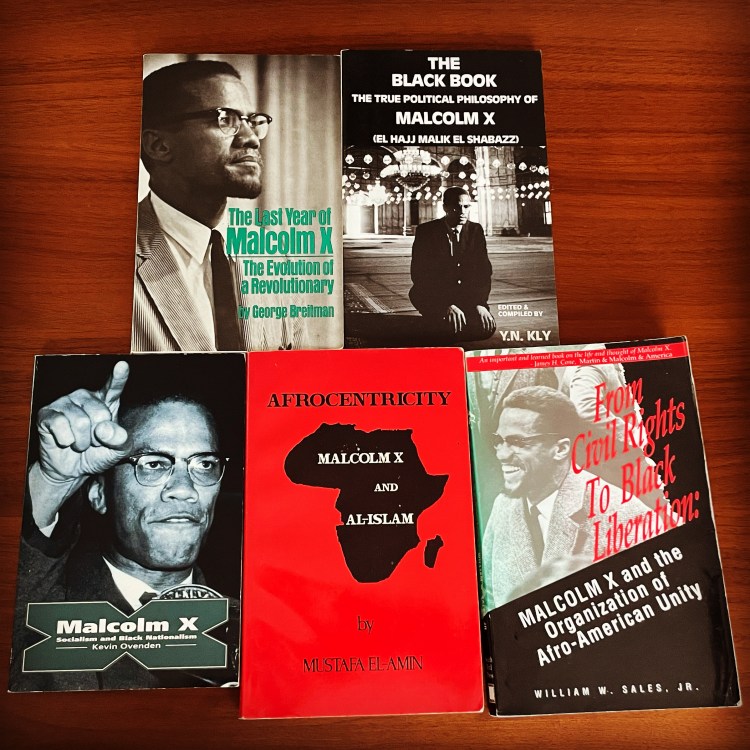

I share now five books from decades past that offer very different interpretations of Malcolm X. The first and earliest book is “The Last Year of Malcolm X: The Evolution of a Revolutionary” (1967) by George Breitman. The author, who’s been mentioned previously, is famous for being a founding member of the Socialist Workers Party in the US. He later oversaw the party’s press Pathfinder, through which so many of Malcolm’s words have come to be preserved in print. In this book, Breitman examines Malcolm X’s political organizing with a socialist lens. The appendices also preserve a number of interesting documents and essays. In 1986, Y.N. Kly, a former chair of the Canadian branch of Malcolm’s Organization of Afro-American Unity (O.A.A.U.), published “The Black Book: The True Political Philosophy of Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik El Shabazz).” In this work, Kly attempts to articulate a political manifesto rooted in the radical thinking of Malcolm X. Interestingly, a few poems are interspersed within the political discourse. Next is “Malcolm X: Socialism and Black Nationalism” (1992), authored by Kevin Ovenden, a noted leftist political activist in the United Kingdom. Unsurprisingly, this work aims to position Malcolm in a fashion similar to Breitman. After reviewing Malcolm’s life and legacy, particularly the Black Power movement, Ovenden argues that a truly revolutionary socialism must overcome racism for the sake of unity. Offering a more religious focus is Mustafa El-Amin’s “Afrocentricity: Malcolm X and Al-Islam” (1994). In this volume, El-Amin focuses a great deal on Malcolm’s journey into Islam while also arguing for the Africanness of the faith. Finally, William W. Sales, Jr., a professor of African American Studies at Seton Hall, published “From Civil Rights to Black Liberation: Malcolm X and the Organization of Afro-American Unity” (1999). The work examines Malcolm’s political thinking, especially its explicitly international orientation as well as the O.A.A.U. and its own influence. As these and others works demonstrate, Malcolm X has meant and symbolized many different things to a wide array of people. Ramadan 14

Ramadan 15

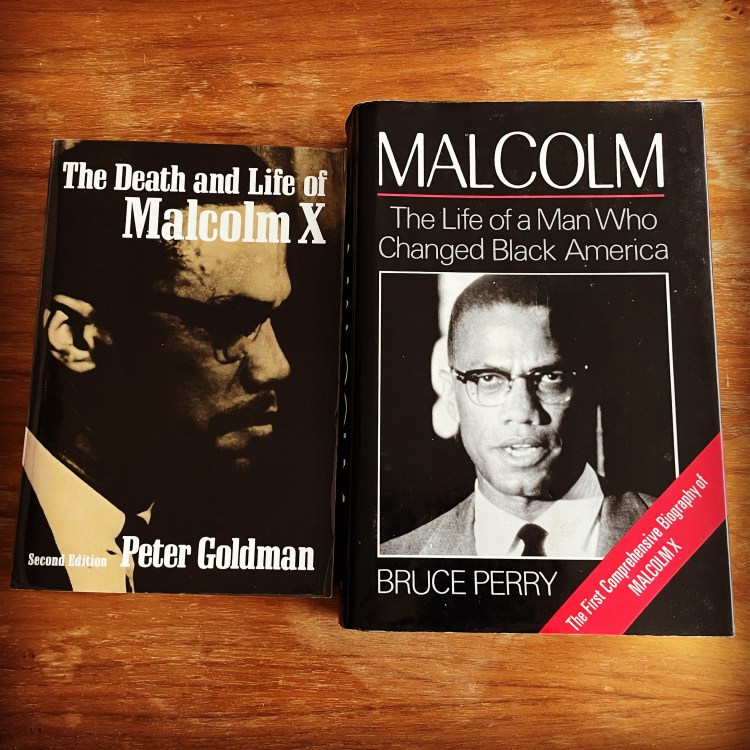

While the Autobiography has remained the touchstone narrative of Malcolm X’s life, a number of biographies have appeared in subsequent years. I’m sharing the first two dedicated biographies to appear here today. First is the work written by Newsweek editor Peter Goldman. Originally published in 1973, this second paperback edition of “The Death and Life of Malcolm X” (1979) includes an epilogue that adds new material raising additional questions about the convicted murderers of Malcolm X. Divided into five parts, Part 1 opens with Malcolm’s assassination but then proceeds to relate his career as an outspoken black voice in America up until the death of President Kennedy. Part 2 continues the story through to a detailed account of Malcolm’s assassination (including a map of the Audubon Ballroom), while Part 3 follows the investigation and trial of his alleged murderers. In Part 4 Goldman offers a retrospective of all that transpired after Malcolm’s death to the author’s present with Part 5 being the newly added epilogue. While offering an interesting account, Goldman’s anxieties as a white man in this era continually bleeds through and colors the story. In 1991 Bruce Perry published “Malcolm: The Life of a Man Who Changed Black America” based on extensive interviews conducted in the years prior. In fact, to read about one of the more extraordinary interviews Perry conducted, turn to the introduction of “Malcolm X: Last Speeches,” which he also edited and that I featured earlier. While offering some new insights and vantages, the biography suffers from tenuous – if not sensationalistic – speculation throughout. He claims, for example, that Malcolm likely firebombed his own home. I’ll simply repeat a line from a contemporary reviewer, “The line between a critical biography and a hatchet job is indeed a thin one. Bruce Perry may have crossed it.” (Baltimore Sun, Dec. 22, 1992). Ramadan 15

Ramadan 16

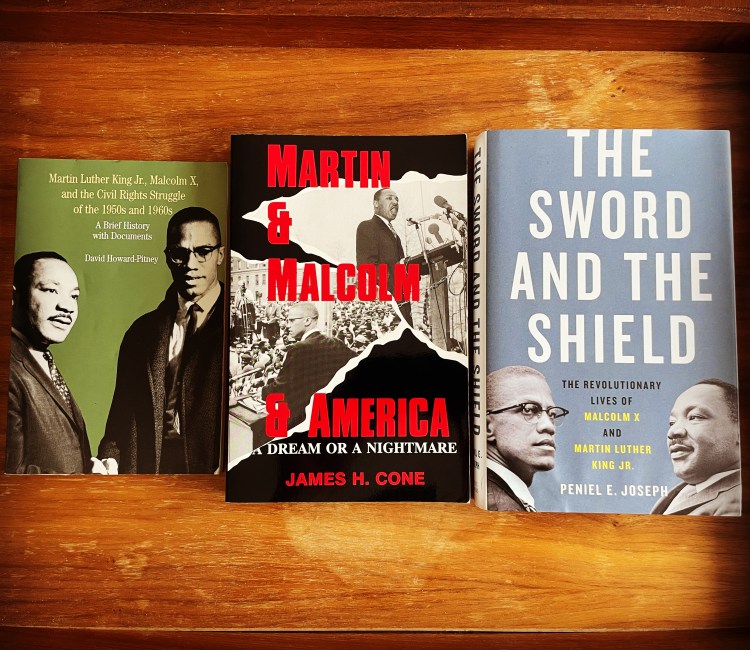

I feature here today three important works that seek to rightly set two iconic figures in contrast and conversation with one another. The first “Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and the Civil Rights Struggle of the 1950s and 1960s: A Brief History of Documents” (2004), edited by David Howard-Pitney, seeks to frame Martin and Malcolm against the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement, an arguably limited frame of reference. What is helpful in this slim volume are the primary documents collected from both men that are arranged around common issues and themes. The other two books were featured back in 2020, but are worth sharing again given this Ramadan’s focus on Malcolm X. James Cone’s “Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare”(1991) is a brilliant theological reading of of both men from an eminent voice of Black Christian liberation theology. While written during Malcolm’s cultural “rediscovery” in the 90s, the book remains a compelling narrative sensitive to the religious dimensions of both men. The more recent “The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.” (2020), written by historian Peniel E. Joseph, is also a worthwhile undertaking in its aim to surface the points of confluence between the two. Here’s an excerpt from Cone’s conclusion: “Charismatic leaders, however, cannot liberate black people from their misery. They may even hinder the process. Thus, it is important to emphasize that Martin and Malcolm, despite the excessive adoration their followers often bestow upon them, were not messiahs. Both were ordinary human beings who gave their lives for the freedom of their people. They show us what ordinary people can accomplish through intelligence and sincere commitment to the cause of justice and freedom. There is no need to look for messiahs to save the poor. Human beings can and must do it themselves” (315). The truth of these words, I believe, extends well beyond the community of which Cone was speaking and we would do well to keep that wisdom close to heart. Ramadan 16

Ramadan 17

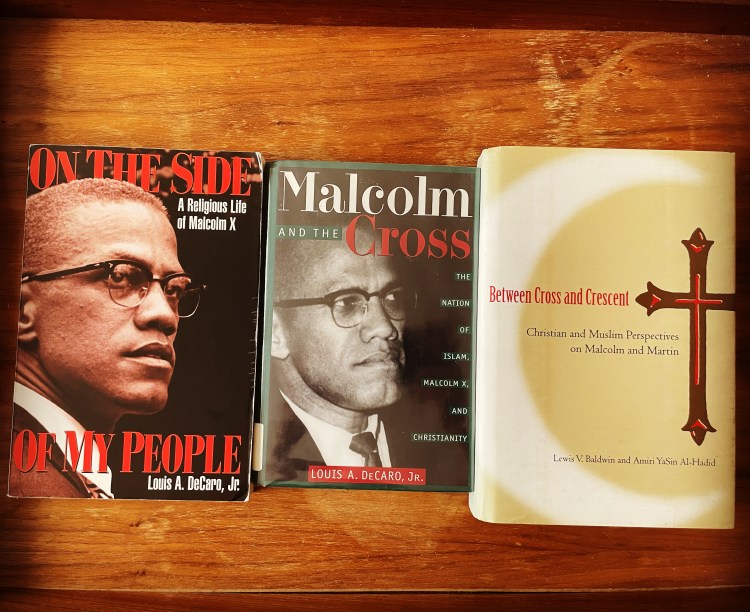

For a long while, the religious treatments of Malcolm X were rare. James Cone’s book shared yesterday was one such important work published early in 1991. Since then, several other important books have appeared. Louis A. DeCaro, Jr. has published two such works, first “On the Side of My People: A Religious Life of Malcolm X” (1996) and “Malcolm and the Cross: The Nation of Islam, Malcolm X, and Christianity” (1998). I find both works important contributions in their own right, though the former, which is exclusively focused on Malcolm X. One benefit it offers is that it explores in detail Malcolm’s various travels and conversations in the Muslim world. A more collaborative book is “Between Cross and Crescent: Christian and Muslim Perspectives on Malcolm and Martin” (2002). Lewis Baldwin, a Christian, and Amiri YaSin Al-Hadid, a Muslim, bring their minds to bear on the lives and legacy of both Malcolm X and Dr. King. In almost alternating fashion, each weighs in on different aspects of these complicated men only offering co-authored pieces at the very beginning and end of the book. From their shared conclusion: “Malcolm and Martin had very definite ideas about the significance of community and how it might best be actualized. Both viewed community as the goal of human existence, as the highest ethical ideal, and as the key to human welfare and survival, but at times they doubted that such a state of existence could be realized in human history. Perhaps more important, they disagreed to a great extent over the best means to achieve genuine human community…” (315-316). Ramadan 17

Ramadan 18

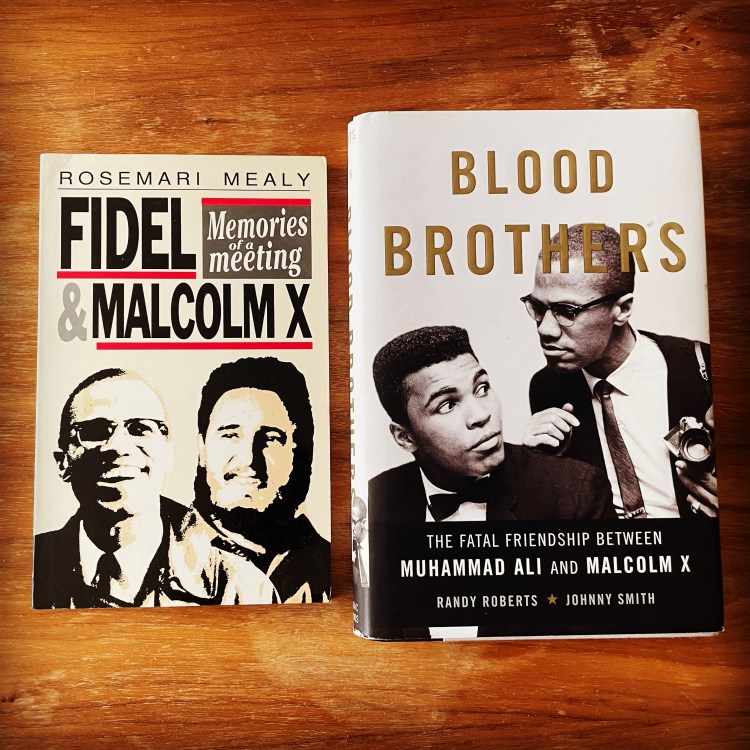

Dr. King is far from the only figure to be set alongside Malcolm X. Perhaps just as notable is Muhammad Ali, with whom Malcolm had a deep and influential friendship until his departure from the Nation of Islam. Sports historians Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith have written an in-depth exploration of Malcolm and Muhammad Ali’s relationship from its beginnings to its tragic end in “Blood Brothers: The Fatal Friendship Between Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X” (2016). Next to it is a work on a less likely pairing with Malcolm, “Fidel & Malcolm X: Memories of a Meeting” (1993) by Rosemari Mealy. This slim volume of 90 pages was written by Mealy as a means of capturing a conference held in Havana, Cuba on May 22-24, 1990, the “Malcolm X Speaks in the 90s Symposium.” Envisioned by Mealy and Assata Shakur, the conference sought to bring together a wide array of Black scholars, writers, activists, and artists to discuss the relevance of Malcolm X in that moment. This work gathers some of the recollections shared at the Symposium while primarily documenting Malcolm X’s historic meeting with Fidel Castro in Harlem at the Hotel Theresa back in September 1960. The book presents these events from a variety of perspectives, including eyewitness recollections and broader reports. Also included in the book are the words of Malcolm X, Amiri Baraka, and Fidel Castro himself, who also made an appearance at the Symposium. Finally, the book also collects a striking set of photographs from that 1960 visit. Despite its modest size, this is a work well worth tracking down. Ramadan 18

Ramadan 19

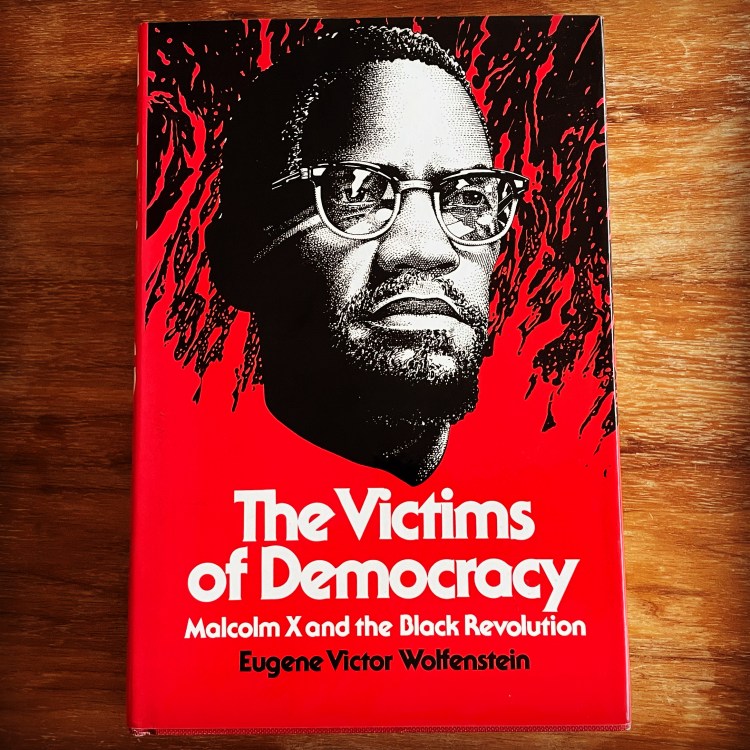

For the next five days, the books that I’ll be sharing are what I would consider academic treatments of Malcolm X. And with that in mind, I wanted to start with what some might be considered the beginning of that. Eugene Victor Wolfenstein’s “The Victims of Democracy: Malcolm X and the Black Revolution” (1981) is arguably one of the earliest scholarly monographs to critically examine Malcolm’s life and thought. A professor of political science, Wolfenstein states that the book is written from a “perspective of Marxist psychoanalytic theory.” Unfortunately, as a result, and despite the aesthetically stunning cover, the work reads very much like so many other academic tomes, dense and jargon-laden. The book initially came to my attention because of a statement made by Joe Wood in the previously shared “Malcolm X: In Our Own Image.” Wood writes, “I kept my focus on Malcolm, conducting research at the college’s enormous library. It was there I found out that the best books on him were written by White people: Goldman, Breitman, Wolfenstein” (2). Much as changed since then thanks to Wood’s work and many other. Ramadan 19

Ramadan 20

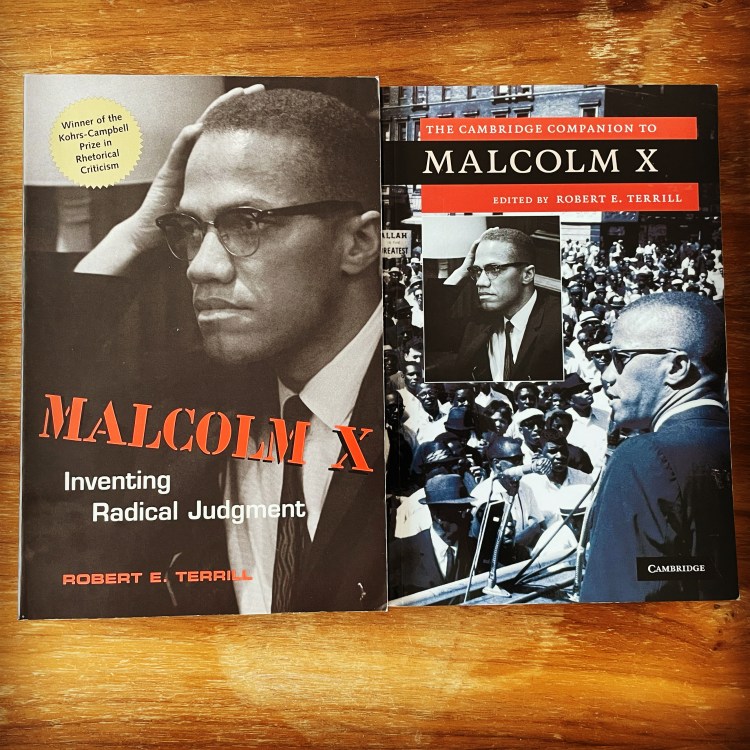

Robert E. Terrill, a scholar of rhetorical criticism, met Malcolm X long ago as a young undergraduate in California. Many years later as a professor, Terrill has gone on to publish two important works in Malcolm X studies. In 2004 he published “Malcolm X: Inventing Radical Judgement,” which closely examines Malcolm’s rhetorical practices and strategies as they grew and developed over the course of his life. I’ve used parts of this text to great effect in the classroom, namely the chapter “Prophetic Precedence” that skillfully works to situate Malcolm in the Black American tradition of prophetic speech. Malcolm’s command of words becomes all the richer once set within this historical constellation. In this work Terrill writes, “Malcolm’s rhetoric after he left the Nation of Islam, in contrast, is characterized by a radical flexibility, a suspicion of constraint and of commitment, and a rejection of formulaic programs. History becomes an open-ended product of human construction rather than the predetermined creation of a divine hand. Identity construction depends on recovering the power to manage its continual remaking to one’s own advantage rather than on assimilating a revealed sense of self that is stable and unchanging” (109). Then in 2010, Terrill edited “The Cambridge Companion to Malcolm X,” which consists of 14 chapters from fellow academics, mostly those in the disciplines of English, Communications, and African American studies, offering their critical assessments. Ramadan 20

Ramadan 21

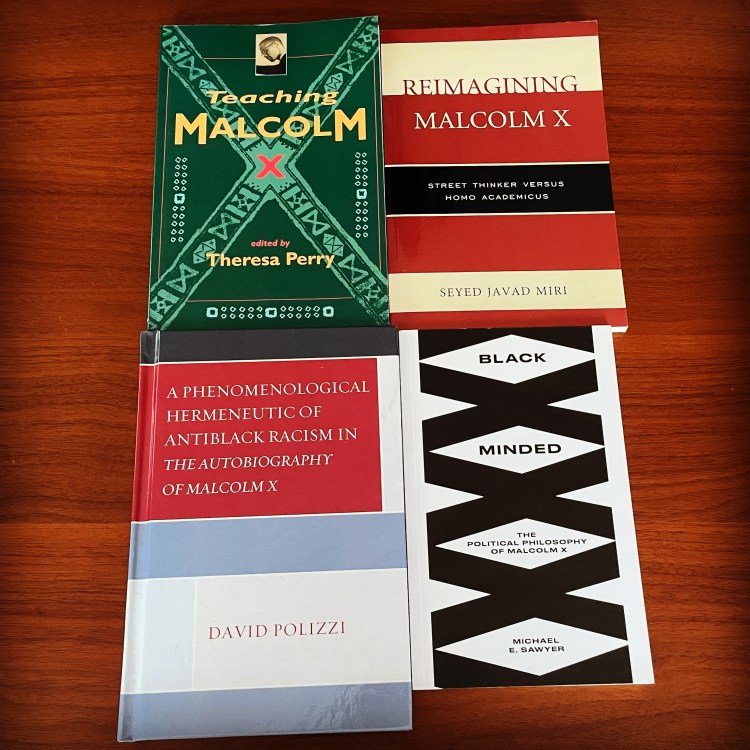

Here are four more scholarly work aimed at critically engaging with Malcolm X. The first, “Teaching Malcolm X” (1996), was edited by Theresa Perry and published by Routledge with a clear and well-achieved pedagogical aim in mind: how might Malcolm X be taught in the classroom. Across 19 chapters, Perry brings together a wide range of voices to weigh in on wide variety of contexts: fifth and sixth graders, white students, urban high school settings, and so on. She also gathers an impress range of voices like Cornel West, Imani Perry, Nikki Giovanni, and Michael Eric Dyson. Published with the University Press of America is “Reimagining Malcolm X: Street Thinker Versus Homo Academicus” (2016) by Iranian social thinker Seyed Javad Miri. A relatively light work, Miri endeavors to present a Malcolm undomesticated by the Eurocentric social sciences. Next is “A Phenomenological Hermeneutic of Antiblack Racism in the Autobiography of Malcolm X” (2019) from Lexingon Books and written by David Polizzi. Taking the Autobiography as his primary source, Polizzi seeks to trace how antiblack racism is confronted at different stages in the narrative. Finally, from the UK-based independent Pluto Press is Michael E. Sawyer’s “Black Minded: The Political Philosophy of Malcolm X” (2020) that offers an insightful analysis of Malcolm’s politics with an aim for laying the groundwork for present day activist efforts. He writes, “…there is a predisposition in the political thinking of Malcolm X that rendered his religion, which at the outset seemed to be the primary driving force behind his political and social resurrection, as a tool rather than a means in and of itself. The Nation of Islam, or Islam more generally, appears to exist for Malcolm X as a vehicle toward a project of radical humanism in the face of subject-deforming forces of oppression. This means that religious practices for Malcolm X must serve to ameliorate real conditions of oppression rather than serve as a means to blunt the effects of subjugation through palliative faith” (15). Sawyer’s preoccupation is one of a universal humanism. Ramadan 21

Ramadan 22

Featuring four books again, I’ll spend more time on the first, which I find the most compelling. “The Geography of Malcolm X: Black Radicalism and the Remaking of American Space” (2006) was written by James Tyner, a scholar of geography, which is a field that gets little attention in North America. As Tyner describes at the outset “This is not a biography of Malcolm X, but rather a geography of knowledge” (1). Later he elaborates: “The geography of Malcolm X’s political transformation, I suggest, is supported by a series of displacements, though two stand apart from the others: first, his philosophical separation from the Nation of Islam and, second, his physical separation from the United States in the form of two sojourns to Africa and the Middle East. However, I argue that this second separation (his travels) would not have impacted Malcolm X to the degree it did without the earlier philosophical separation” (17). Next is Marika Sherwood’s “Malcolm X Visits Abroad: April 1964-February 1965” (2011), which methodically traces Malcolm’s international travels in the last months of his life. The final two books examine Malcolm X alongside two other figures. Written by William David Hart, “Black Religion: Malcolm X, Julius Lester, and Jan Willis” centers Malcolm X but sets him alongside two other black figures who Hart names as two “spiritual children” that also penned religious autobiographies. Julius Lester published in 1988 “Lovesong: Becoming a Jew, while Jan Willis published in 2001 “Dreaming Me: From Baptist to Buddhist, One Woman’s Spiritual Journey.” The other work “Africa in Black Liberation Activism: Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael and Walter Rodney” (2017), by Tunde Adeleke, traces a compelling line connecting the three named “Diaspora activists” to the struggle in Africa and beyond. Given the pan-Africanist focus of the overall work, I’ve found the chapter on Malcolm X helpful in the classroom when teaching him. Ramadan 22

Ramadan 23

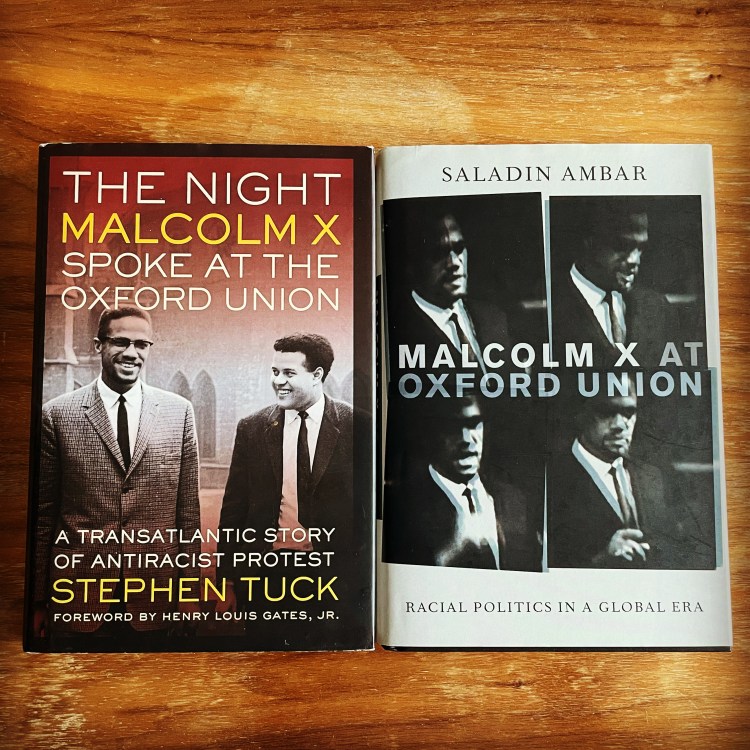

Two months prior to his death on December 3, 1964, Malcolm X engaged in a well-documented debate at the Oxford Union. The topic of debate that evening was “Extremism in the defence of Liberty is no vice; moderation in the pursuit of Justice is no virtue” for which Malcolm spoke in favor. While he was one of six speakers to address the topic, his presence and voice proved to be central to the affair. Almost fifty years later, published in the exact same year, are two works aimed at analyzing and engaging with the proceedings of that night. In “The Night Malcolm X Spoke at Oxford Union: A Transatlantic Story of Antiracist Protest” (2014) Stephen Tuck provides a wider view situating the debate within its broader historical context. Saladin Ambar, in “Malcolm X at Oxford Union: Racial Politics in a Global Era” (2014) uses the address delivered by Malcolm X that night as the foil to explore broader themes and issues. In addition, this second book provides a transcript of Malcolm X’s remarks at the end after the Epilogue. From Malcolm’s address: “I think the only way one can really determine whether or not extremism is defense of liberty is justified, is not to approach it as an American or a European or an African or an Asian, but as a human being… if we look upon it, if we look upon ourselves as human beings, I doubt anyone will deny that extremism, in defense of liberty, the liberty of any human being isn’t a vice. Anytime anyone is enslaved, or in a way deprived of his liberty, if that person is a human being, as far as I am concerned he is justified to resort to whatever methods necessary to bring about his liberty again” (171). Ramadan 23

Ramadan 24

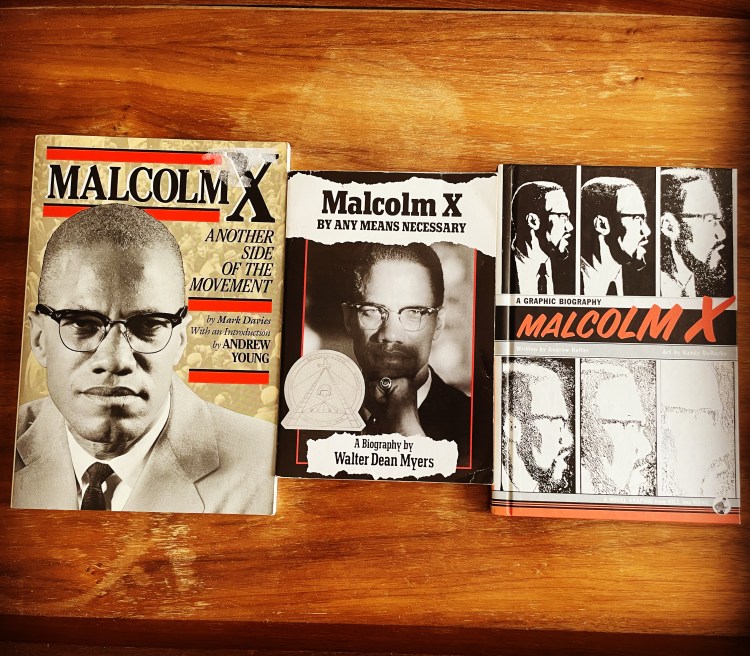

Stepping away from academic works, I’m sharing today three works aimed at different audiences. The first two works are short books aimed at younger readers. The first is “Malcolm X: Another Side of the Movement,” (1990) which is part or a larger series named “The History of the Civil Rights Movement.” Its author, Mark Davies, has tailored this work to fit a younger readership, an aim of the overall series. The work tries to include Malcolm X into a movement that he himself was keen to distinguish himself from for most of his public career. Placing him on “another side” of it strikes me as an ideologically-driven stretch. Next is Walter Dean Myers’s “Malcolm X: By Any Means Necessary (1993),” which appeared several years later from that well-known school-oriented educational press Scholastic. Both works present a more streamlined narrative of Malcolm’s life with accompany period pictures or famous photographs. What I found most interesting, however, is this graphic novel rendition written by Andrew Helfer with art of Randy DuBurke. “Malcolm X: A Graphic Biography” (2006) presents the life of Malcolm X in striking black and white bring Malcolm’s life and struggles to life in an accessible but also compelling way. I’m fairly certain that nearly a decade ago I found a copy of this work in Turkish, which became heavily water damaged in an unfortunate spill. Despite some concerted searching I haven’t been able to find that copy. Ramadan 24

Ramadan 25

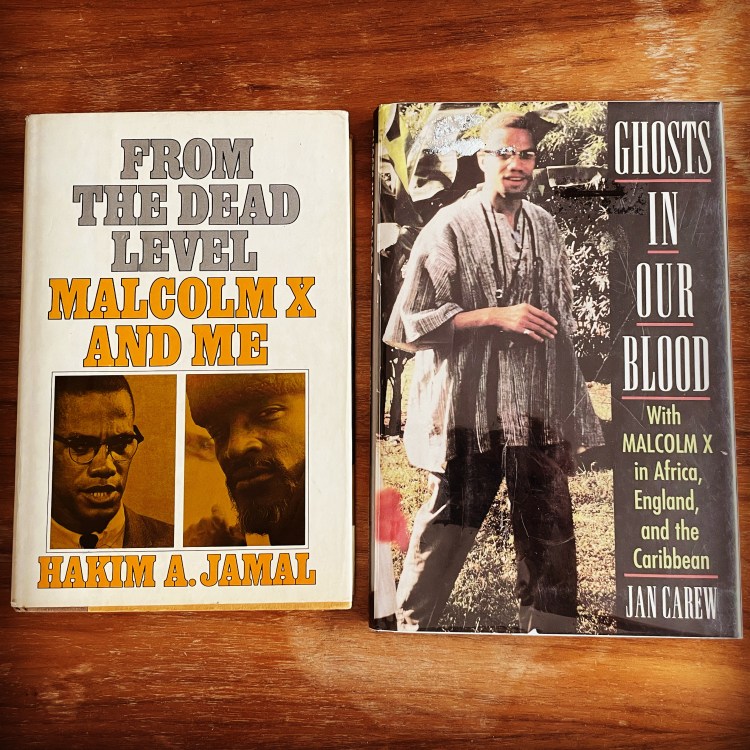

As may be apparent, I’ve spent some time growing my Malcolm X book collection. Today and tomorrow’s posts feature those harder to find works, all of which are memoirs or biographies. In pursuit of these I have had to diligently scour my fair share of used bookstores and their online equivalents. To the latter end, vialibri.net is an invaluable resource. It not only searches the usual online sites but is also linked to numerous independent antiquarian booksellers. With that said, here is Hakim Jamal’s “From the Dead Level: Malcolm X and Me” (1972), a memoir of his life with Malcolm X. The book begins with his time as a youth, then known as Allen Donaldson, and his time spent with Malcolm during his time as “Red.” After recounting this troubled time in Jamal’s life, he then turns to his first meeting with the rebranded “Malcolm X” and continues from there. The book is also remarkable for the words of Malcolm that Jamal recalls – words that are not otherwise preserved elsewhere, at least not at that time. In the Preface he explains: “There are no tape recordings of any of the lectures by Malcolm X that appear in ‘From the Dead Level.’ I have never seen any transcripts. The words of Malcolm X quoted in this book are from my memory…” Next is Guyanese novelist and Pan-Africanist Jan Carew’s “Ghosts in Our Blood: With Malcolm X in Africa, England, and the Caribbean” (1994). A relatively short book Carew recounts their meeting in London when Malcolm X was there in February 1965. He relates their exchanges over the course of Malcolm’s four days there speaking at the Oxford Union and the London School of Economics. Unsurprisingly, Carew’s account is insightful and engaging. “‘When will it end Malcolm?’ I asked ruefully. ‘When everyone comes on deck and seizes the ship with the help of some white sailors who hated the job they were doing and who realized that when Black folks were liberating themselves, they were also liberating them from having to be oppressors'” (53). Ramadan 25

Ramadan 26

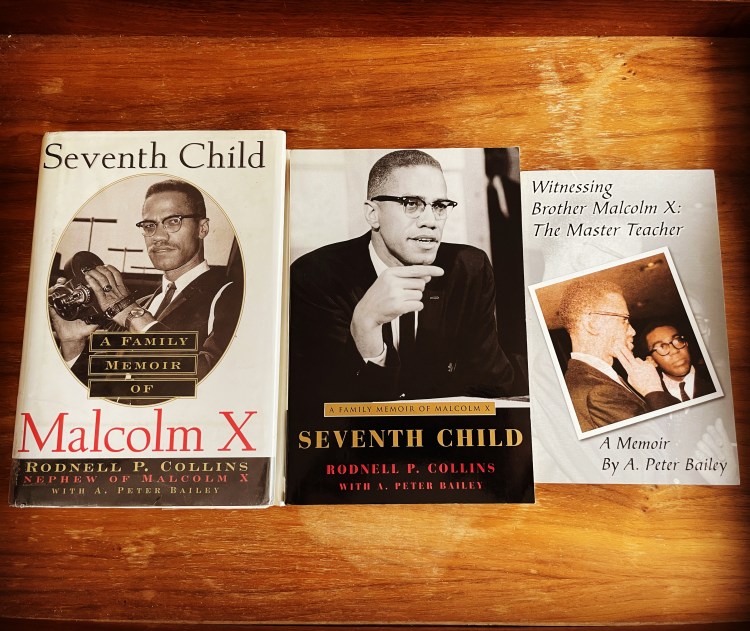

The next set of books are connected by journalist A. Peter Bailey. He worked with Rodnell Collins to write “Seventh Child: A Family Memoir of Malcolm X” (1998), which was first published by Birch Lane Press of the Carol Publishing Group. Rodnell Collins is the son of Ella Collins, who was Malcolm X’s older half-sister and a longtime support in his life. When I first featured this book in 2021 I noted: “The memoir was originally undertaken by Ella Collins, tentatively at first in the 1960s. In subsequent decades she began to take notes and record down her memories. Rodnell began aiding his mother in 1984 after he retired from his tennis career. As the years went on and Ella’s health declined, Rodnell’s role in the project grew until he found himself at the reins.” What Bailey and Rodnell produced is a riveting and unique recounting of Malcolm’s life that is also a deep look into the often overlooked personality of Ella Collins. This book was once hard to find. In addition to the hardcover I eventually found this paperback reprinting from 2002 from Dafina Books of the Kensington Publishing Corp. Fortunately, its rarity is all but gone since it was finally republished most recently in 2022 by Dafina once more. Much harder to find is A. Peter Bailey’s own work “Witnessing Brother Malcolm X: The Master Teacher, A Memoir” (2013) from Llumina Press. I was only able to find this with some help from my friend Abdul-Rehman Malik, who is equally invested in the book hunt. As for the memoir, it not only relates Bailey’s time with Malcolm X, whom he first met in 1962, but also contains his thoughts on Spike Lee’s film and recounts the OAAU, in which Bailey was involved, in both its early and later years. “He was my mentor, as in ‘a wise and trusted advisor.’ Though I was never inspired to become a Muslim, I had recognized that he was not only dealing with politics and economics, but with values and spirituality” (16). Ramadan 26

Ramadan 27

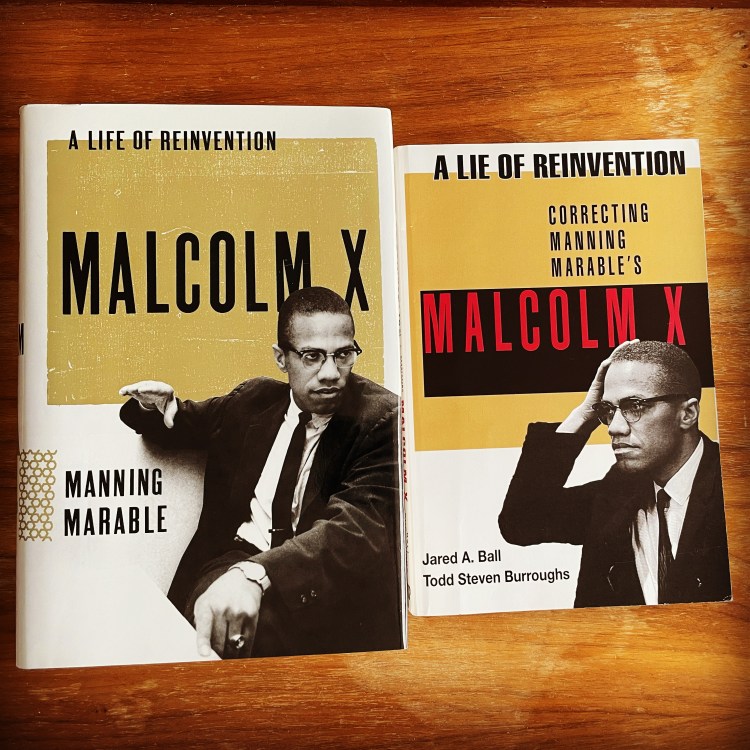

After years of work, Manning Marable’s biography of Malcolm X “Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention” appeared in 2011, the same year that the author passed away. The very next year, 2012, Marable was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize in History for the book. The new biography garnered incredible attention upon publication. With it also came criticism. Next to it is one of two work that gather the many and varied reactions to Marable’s important work of scholarship. Edited by Jared A. Ball and Todd Steven Burroughs is “A Life of Reinvention: Correcting Manning Marable’s Malcolm X” (2012), bearing a cutting title that reflects the sharp, but diverse responsa contained within. Several previously featured writers from this month appear here like Rosemari Mealy, Karl Evanzz, A. Peter Bailey, and William A. Sales, Jr. Not shown here but joining in the same critical spirit is “By Any Means Necessary: Malcolm X: Real, Not Reinvented” (2012) edited by Herbert Boyd, Ron Daniels, Maulana Karenga, and Haki R. Madhubuti. If the late 80s and early 90s are typically thought of as an era of Malcolm’s rediscovery, I think an argument could be made that another wave of interest has grown since the 2010s that has not really abated since. Marable’s work, I’d argue, was among the reasons for this second wave of renewal. Ramadan 27

Ramadan 28

The most recent biography of Malcolm X is “The Dead are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X” (2020) originally written by Les Payne, but brought to completion by his daughter Tamara after his death in 2018. Like Marable, Les Payne had spent decades researching this work, but whereas Marable wrote as an academic, Payne proceeded as a journalist and was a noted one at that. He earned several Pulitzers while working at Newsday and another posthumous Pulitzer in 2021 for this book. Imminently readable, the biography offers a rich and renewed look at Malcolm’s early family life building upon the many interviews that Payne conducted. And like previous biographies, Payne also raised substantive questions surrounding Malcolm X’s assassinations, questions that have since been investigated to justify these long running doubts across the decades. There are other rich areas explored as well, like how Malcolm went about recruiting new members while with the Nation of Islam and his engagement with the broader media as well. Ramadan 28

Ramadan 29

As the month of Ramadan draws to a close, I am sharing today two recent books involving Malcolm. The first, is less direct, but important given this month-long focus on a single man. In 2021, Anna Malaika Tubbs published her important book on three remarkable women, “The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation.” Rather than treating the lives of these women separately, the respective stories of Alberta King, Louise Little, and Berdis Baldwin are interwoven into a shared and powerful narrative. Next to it is a work brought to my attention by Abdul-Reman Malik, “Divine Rage: Malcolm X’s Challenge to Christians” (2023) by Marjorie Corbman. Published by Orbis Press, this theological work explores how Malcolm’s righteous call to confront structural oppression shaped and influenced an array of faith leaders, organizers, and theologians like Albert B. Cleage, Jr., James Cone, Thomas Merton, Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons, Jose Jiménez, Marsha P. Johnson, and Sylvia Rivera. Prior to these explorations, Corbman furnishes a compelling exploration of Malcolm’s own work and theology as well as tracing out his immediate heirs in the Black Power era. Ramadan 29

Eid 1

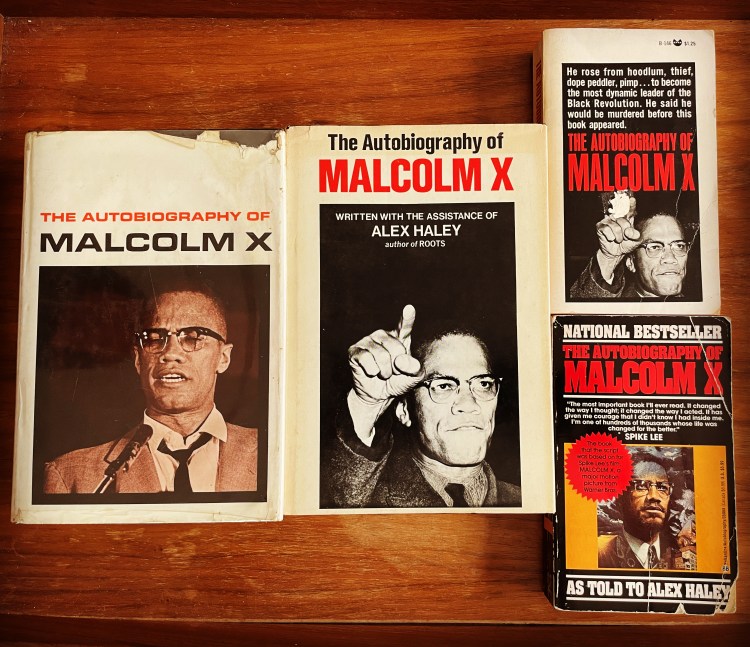

Eid Mubarak. For the next few days I’ll close out this month-worth of book sharing with some special pieces. The first, of course, is “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” written with Alex Haley and first published shortly after Malcolm X’s death in 1965. I share with you here the fews editions of the book that I’ve come to own. The two hardcovers are very early editions. The leftmost one is a fourth printing of the first edition of the book that appeared in 1965. Incredibly, I found this at a used bookstore for $5. When I write and have to reference the Autobiography, I invariably cite the pagination of this edition. The hardcover next to it, which shares the same pagination, was published some time after (perhaps not long after), but it is unclear to me when it first appeared as no printing or edition information is disclosed in its pages. Notably, the former first edition copy makes no mention whatsoever of Alex Haley on the front cover, spine, or back, while the latter copy has added clear attributions to Haley on all three. Additionally, the back cover lists praise from various major review outlets like The New York Review of Books, Newsweek, and the New York Times whereas the first edition only provides a lengthy excerpt from the text itself for prospective readers. The two paperback editions, which have differing paginations, are also from different times as well. The topmost copy with the same photograph as my second hardcover edition is a twentieth printing of the first paperback edition published in 1966. I picked this copy up from a sidewalk bookseller in New York City many years ago. The other paperback is the thirty-fourth printing from April 1993 of the first Ballantine Books edition that appeared in 1973. I’ve had held onto this particular paperback for quite some time since this was the copy that I first read in what feels like a lifetime ago. Much of my thinking and formation is indebted to this work by Malcolm. Eid 1 of 3.

Eid 2

Moving towards ephemera, here are two pieces (top row) – that are more pamphlets than books (both have saddle stitch binding, i.e. staple bound) – that were produced by Merit Publishers in New York City. “Malcolm X on Afro-American History” was first published in February 1967. This copy is the second printing from December 1967 that I found for $20 at a now shuttered used bookstore in Milford, CT. At 46 pages in length it reproduces a transcript of a tape recorded lecture delivered by Malcolm X on January 24, 1965. Besides the talk itself there is only a brief two page introduction from George Breitman. Beneath it is a later printing of the same work, this time with Breitman’s Pathfinder Press and perfect bound as a softcover book. This copy appeared in 1990 and is substantially expanded to 102 pages. It includes the original speech as well as excerpts from the Autobiography, relevant excerpts from other speeches by Malcolm, and a Preface by Steve Clark that replaces Breitman’s original introduction. “Two Speeches by Malcolm” was also published by Merit Publishers and this copy is the seventh printing from March 1969. It contains Malcolm X’s announcement of his break with the Nation of Islam from a March 12, 1964 press conference, his “Black Revolution” speech delivered on April 8, 1964 in New York, and his “Prospects for Freedom in 1965” speech delivered before the Militant Labor Forum on January 7, 1965. Filling in the rest of the booklet’s 31 pages are excerpts from interviews that Malcolm gave in the last year of his life. I was glad to come across this in a used bookstore for $7.50. The final book shown here is “By Any Means Necessary: Malcolm X,” which is another collection of speeches that I had overlooked until my friend Sohaib Khan mentioned it earlier this month. Originally published in 1970 with Breitman’s Pathfinder, this copy is an eighth printing of the second edition published in 2003 and documents statements, interviews, and speeches given across 1964 into early 1965. Eid 2 of 3.

Eid 3

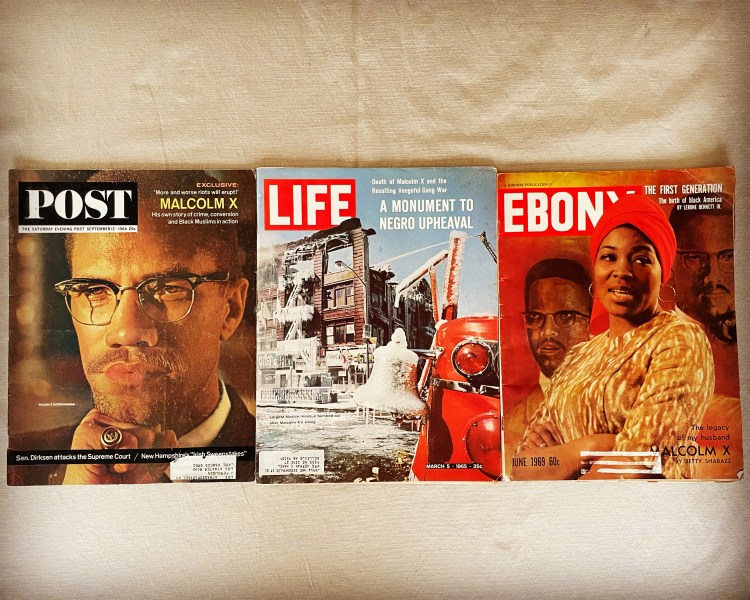

To end this series here are three magazines. On the fourth of Ramadan I shared a book by photojournalist John Launois. Here is the issue of “The Saturday Morning Post” (September 12, 1964) where his work would appear. The article itself was an excerpt from “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” that was intended as a preview of the book to appear the following year. In the Post, the article found inside is entitled “An Autobiography by Malcolm X – I’m Talking to You, White Man.” It is remarkable to think back to what the Autobiography must of looked like at this precise moment, a narrative that had yet to include Malcolm’s Hajj or the full experience of his travels abroad, matters that would eventually make their way into the final book. Two weeks after Malcolm X’s assassination this issue of “Life” (March 5, 1965) appeared featuring the frozen, burnt out husk of what was once Harlem Mosque No. 7, set ablaze in the wake of Malcolm’s demise. Gordon Parks penned “The Violent End of the Man Called Malcolm X” found within. Three tragic photos taken minutes after Malcolm X was shot open the piece. Notably, in the first photo is Yuri Kochiyama, who was among the first to rush to Malcolm’s side and who I discussed in 2021. In the third is Malcolm’s wife Betty Shabazz kneeling beside her slain husband. They are bitter and poignant images. I found both these magazines at the same time years ago at an ephemera shop in New Orleans for $50 and $20 respectively. A more recent acquisition is this issue of “Ebony” magazine (June 1969) featuring Betty Shabazz. Here on the cover she is in front of an immense painting of her husband that adorned her living room. Within is an article by Betty Shabazz entitled “The Legacy of My Husband, Malcolm X.” Shabazz shares how Malcolm’s words and example continued to inspire the next generation of Black youth in the struggle for liberation as well as the personal struggles she and her daughters had in having to live with his sudden loss. She also powerfully recalls how Malcolm was in life as a husband and exemplar. With respect to Black youth, Shabazz writes, “Against staggering odds, as if by a miracle, they have gone beyond such crippling historical forces as slavery and found themselves. Like their ancestors in ancient Africa – where life and civilization began – they are once again the givers of the Code of Brotherhood and the originators of the mutual recognition of another’s right to exist. Malcolm made them understand that this Code of Brotherhood was taken from them by the white man who, in turn, used it to maintain his own freedom and to oppress and enslave the rest of the world. While many blacks hoped that some day things would change, Malcolm drove home his message that hope is not enough- that we black people in America must form our own destiny” (176). I have shared these many works this past month in honor of Malcolm X and in hopes it will inspire others to engage with his words and legacy. Eid 3 of 3.