As we entered Ramadan in 2024, the call for liberation pervaded the air. It seemed necessary to make that the theme of this fifth year of the bookshare. Back to the MRB.

Prelude

Yesterday evening I began plotting out what has now become a fairly comforting and welcome Ramadan tradition… selecting the works that I’ll share for the monthlong bookshare culminating with Eid, insha’Allah. Not yet finalized, always open really until the books are posted.

Sha’ban 29

Since 2020, I have spent part of every Ramadan sharing with you the books that have and are shaping my thinking and life. Last year, I decided to dedicate every day of the blessed month to the many works written about Malcolm X, whose words and actions remain strikingly relevant to this day. I’ve debated continuing with a theme or reverting back to the open and capacious field of consideration with which I began all this. Given the ongoing suffering and genocide we see unfolding before our eyes, I’ve decided to continue with a theme: liberation. I’ll be featuring (God willing) books born out of an aspiration for liberation. With that said, we are in the last hours of the month of Sha’ban with the month of Ramadan about to begin at sunset (insha’Allah). I’ve decided to post a book now that will serve as a bridge between last year’s bookshare and this one’s, “Malcolm X’s Michigan Worldview: An Exemplar for Contemporary Black Studies,” edited by Rita Kiki Edozie and Curtis Stokes. Arriving after the conclusion of last Ramadan, I’m happy to share this volume of collected essays published in 2015 where scholars weigh in afresh on the meaning and significance of Malcolm X from a variety of perspectives. May his life, death, and legacy continue to guide, provoke, and inspire. Sha’ban 29

Ramadan 1

We enter Ramadan in the midst of a long and terrible storm. For more than 150 days a near continuous stream of suffering and destruction in Gaza has unfolded before our eyes. It continues to overwhelm that small strip of land and the deaths continue to mount. Catastrophe is being meted out upon Palestine yet again. Starvation has joined the fray. These seemingly ceaseless days have been immensely trying and the discourse around it all has been willfully obfuscated, if not completely disfigured beyond reasonable recognition. The right words to analyze and understand it all are being removed from mouths, pulled from print, and relegated to social media shadows. Yet some words when written persist and if we take the time to read them they’ll take us to the heart of things. They’ll take us back to the much longer history underlying the current tragic moment. I share, then, one work that remains a helpful record and guide for understanding what we are witnessing today, even if it was written several years ago. Rashid Khalidi’s “The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine” (2020) helpfully relates this past from the analytical frame of settler colonialism, a legacy with which the United States is intimately and perversely familiar. The book proceeds methodically through the decades down to the near present. While there are many other historical works to reference, this one seems to rise to the fore time and again as especially rigorous, insightful, and compelling. As we begin our days of fasting, let us not lose sight of Palestine. As Fannie Lou Hamer declared, “Nobody’s free until everyone’s free.” Ramadan 1

Ramadan 2

The 70th anniversary of the Palestinian Nakba took place in 2018. The next year, this book “An Oral History of the Palestinian Nakba” (2019) appeared, edited by Nahlo Abdo and Nur Maslaha. Collecting a thematically-bound set of critical essays, the work makes a number of interventions as how we might think about the “catastrophe” of 1948 all the while building upon the voices of those, particularly women, who survived it. The essays included intimately weave into their analysis the testimonies related and preserved through the work of interviews and oral history – an especially salient endeavor given the present catastrophe being executed before our eyes. Here is the testimony of Ameeneh Abdelhameed Ataba recounting her displacement from her home in Saffourieh, “It was during the month of Ramadan. People were just breaking their fast. Suddenly, they saw the tanks. Two tanks barged into the town. Our house, that is our land, was close to the street. The residents of Saffourieh, the gardeners, once they saw the tanks entering the town started saying: there are barrels behind them and others would say, there is something happening, we do not know! They could hear the tanks, they started shouting, they entered and it meant occupation. The gardeners backed away, they backed away. They hid amidst the pomegranate trees. My mother was pregnant in her ninth month and I was a little girl. They grabbed us and took us to hide amidst the pomegranate trees” (162-163). Ramadan 2

Ramadan 3

Following in the spirit of the previous book is “Voices of the Nakba: A Living History of Palestine” (2021), edited by Diana Allan. This book is similarly based on remembered testimonies of life before and during 1948. While published in 2021, this collection features interviews collected primarily “in the early 2000s, in the wake of the 1993 Oslo Accords, when the Palestinian leadership appeared to have abandoned refugees, implicitly signalling its willingness to exchange their right of return for statehood” (3-4). Focusing again on Ramadan, here is an excerpt from an interview with Ismail Shammmout as he recounts his family’s expulsion from his hometown of Lydda in Palestine: “Naturally July is hot. There was no water. It was Ramadan. Children started screaming and crying because this one was thirsty and this one was tired, and people walked down the path that was designated for them, heading east. We passed through the centre of Lydda and I saw with my own eyes the stores that were broken into and violated; they were opened with axes and everything in there was turned upside down. While we walked, we found martyrs, killed, a corpse here, a corpse there. It got hotter… I found a faucet and struggled to open it, until water started running from it, so I found a bucket or something and filled it with water. People saw me and they all ran towards me because everyone wanted water. As I finished filling the bucket and headed to join my parents, I saw a jeep driving fast and it stopped right at my feet. An officer came down and put a gun against my head. He told me, ‘Throw water, throw water, throw water!’ What do you mean throw water? A guy had a gun to my head, you forget about water and you forget everything. Of course, I threw the water. I thank God that he didn’t shoot me.” (246-247). Ramadan 3

Ramadan 4

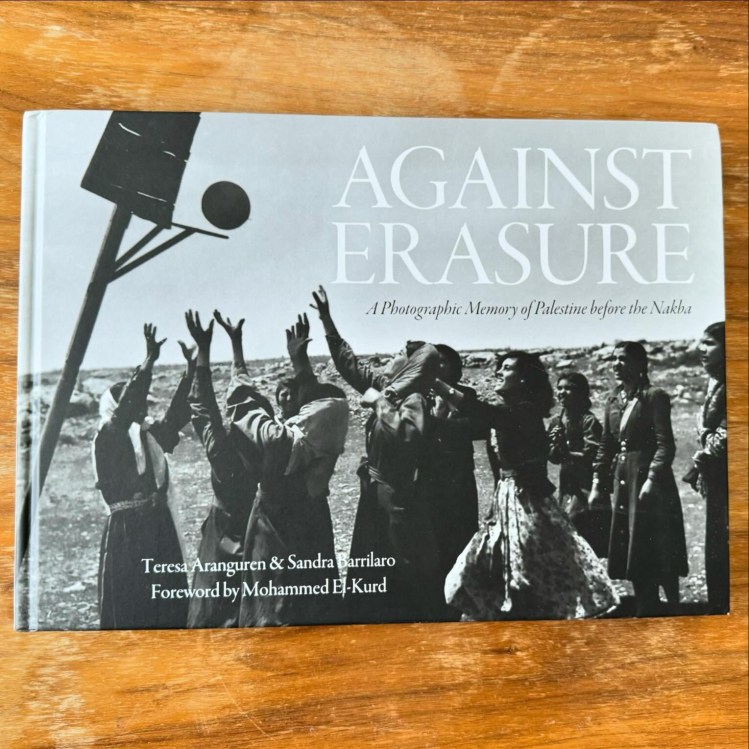

After hearing poet Mohammed El-Kurd speak last year, I learned that he had penned the foreword to this (at the time) forthcoming book. First published in Spanish in 2019 in Madrid, this English edition and translation was just released earlier this year (February 20) thanks to Haymarket Books. It’s arrival is especially poignant and significant given the latest and ongoing catastrophe decimating Gaza and its people. With captions in both English and Arabic, “Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine before the Nakba” is a visual journey into a rich and vibrant past that has been systematically obfuscated and suppressed. With each photograph the communities that once were come alive again. Here are images as resistance. From the 2024 Foreword by El-Kurd writes “…the Nakba breathes down our necks, invading our national identity and contorting our earliest encounters with our own sense of self. It is relentless. It happens in the present tense, everywhere on the map” (ix). Then, he writes, “Before conjuring the ability to write a few coherent paragraphs prefacing this book, all I could think while flipping through these photographs was ‘What have they done to you? What have they done to Palestine?’ I was struck by images of Palestine before the walls and the colonies, and checkpoints clogged its arteries; photos captured between towns and villages, now separated by concrete barriers and pulled worlds apart, that before were intertwined socially and economically” (xi). In addition to the two forewords (2019 and 2024) are several other essays included to better contextualize this photographic collection and rightfully disruptive intervention. Ramadan 4

Ramadan 5

All too often, we make little time for poetry, yet the voice of liberation is perhaps most strong or clear when it finds its form in the poetic. Here is the 2022 collection “Things You May Find Hidden In My Ear” by Mosab Abu Toha. In his poem “My City After What Happened Some Time Ago” he concludes with this final stanza:

In Gaza, some of us cannot completely die.

Every time a bomb falls, every time shrapnel hits our graves,

every time the rubble piles up on our heads,

we are awakened from our temporary death. (39)

The book ends with an interview. Here is Abu Toha on the topic of poetry: “The word for poetry in Arabic, sha’ir, doesn’t refer to a particular form, it only has to do with feeling. So you have to be an expert in showing your feelings on paper or reciting your poetry to people so that they can feel what you’re feeling. It can be an image but it does have to leave an impact on the reader. And if you can make them cry or smile, then you are a poet; if you can make them shiver, then you are a poet. When you are a poet, you need to be saying something that cannot be said by other people. Poets don’t necessarily need to be first-rate readers of poetry, because when they start to write poems they already have what they need, they’ve been living it. When I tell my story-to anyone-it’s as if I’m reciting poetry” (106). Ramadan 5

Ramadan 6

Here is the compelling opening to the first chapter of Michael R. Fischbach’s “Black Power and Palestine: Transnational Countries of Color” (2019): “On September 4, 1964, an Egyptian government car departed Cairo and headed east, crossing the Suez Canal and continuing across the hot desert of the Sinai Peninsula before finally arriving in the town of Khan Yunis in the Gaza Strip. Gaza was crammed full of Palestinians refugees, hundreds of thousands of exiles who had fled or been expelled from their homes by Israeli forces during the Arab-Israeli war of 1948. One of the passengers in the car was keenly aware of what it meant to be an exile from one’s original homeland: Malcolm X, who passionately fought for the freedom of blacks in America who lived hundreds of years and thousands of miles from their ancestral homelands in Africa… Malcolm X was a towering figure in the emergence of the Black Power movement during the 1960s, and his solidly pro-Palestinian stance on the Arab-Israeli conflict was the culmination both of his Islamic beliefs and of his keen sense of global black solidarity with liberation struggles being waged by kindred people of color (9-10).” This, however, is just the beginning of the book. Fischbach goes on to cover critically a range of other black actors and their engagement with Palestine including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Dr. King, Bayard Rustin, the Black Arts Movement, the Black Panthers, Jesse Jackson and on through to the present. The language of liberation is shared by many. Ramadan 6

Ramadan 7

Angela Davis has been a longtime political activist and scholar at the forefront of liberation causes. While perhaps best known for her staunch acts of resistance early in her life or her present prison abolition work she has also been an ardent and steady advocate for Palestine. This book “Freedom Is A Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement” (2016) brings together many of Davis’s pieces, speeches, and interviews from 2013 to 2015. Her concern for Palestine can be found throughout the volume’s pages. I wanted to share, however, the following passage from the end of a speech delivered in London at SOAS on December 13, 2013: “And so if we say abolish the prison-industrial complex, as we do, we should also say abolish apartheid, and end the occupation of Palestine! In the United States when we have described the segregation in occupied Palestine that so clearly mirrors the historical apartheid of racism in the southern United States of America – and especially before black audiences – the response often is: ‘Why hasn’t anyone told us about this before? Why hasn’t anyone told us about the segregated highways leading from one settlement to another, about pedestrian segregation regulated by signs in Hebron – not entirely dissimilar from the signs associated with the Jim Crow South? Why hasn’t anyone told us about this before?’ Just as we say ‘never again’ with respect to the fascism that produced the Holocaust, we should also say ‘never again’ with respect to apartheid in South Africa, and in the southern U.S. That means first and foremost, that we will have to expand and deepen our solidarity with the people of Palestine.’ Ramadan 7

Ramadan 8

Yesterday I featured Angela Davis, who was a member of the Black Panther Party for a time. Today I’m sharing two works on this Black Power political organization that was founded in 1966. On the left is “Revolutionary Suicide” (2009), which was first published in 1973 and is the autobiography of Huey Newton, one of the founders of the Black Panther Party. He opens the work with “A Manifesto” that is entitled “Revolutionary Suicide: The Way of Liberation.” At its end Newton writes, “The concept of revolutionary suicide is not defeatist or fatalistic. On the contrary, it conveys an awareness of reality in combination with the possibility of hope – reality because the revolutionary must always be prepared to face death, and hope because it symbolizes a resolute determination to bring about change. Above all, it demands that the revolutionary see his death and his life as one piece.” Next to it is Peniel Joseph’s “Waiting ‘Til The Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America” (2006), a riveting retracing of the Black Power movement that begins with Malcolm X and provides incredible coverage of the Black Panther Party among others. In the Epilogue Joseph states, “Black Power’s impact remains powerfully resonant – if also fraught and contentious – in American social and political institutions. Indeed, a generation of politicians, artists, and intellectuals have channeled black identity as first articulated by Black Power in ways that found a creative outlet in domestic and international affairs, education, and political and cultural activism” (302). Ramadan 8

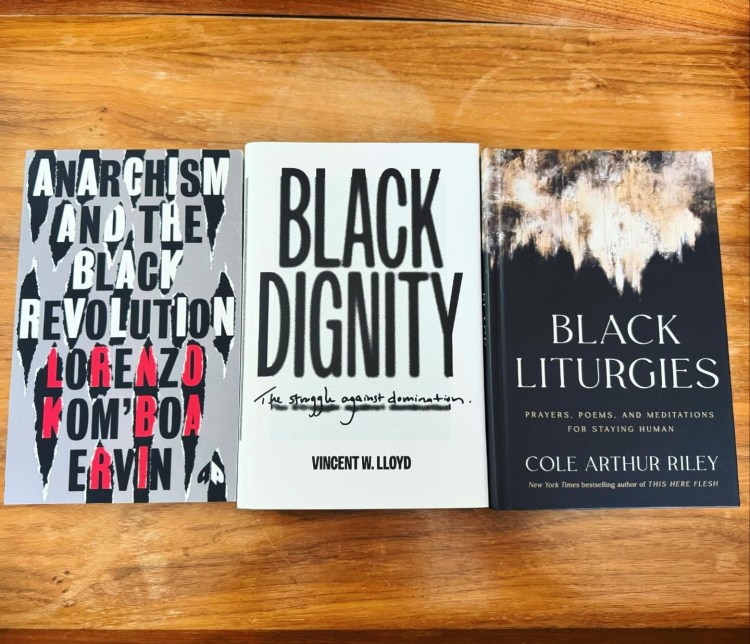

Ramadan 9

Here are three books that approach Black liberation from three distinct, but not unrelated vantages. “Anarchism and the Black Revolution” (2021) is by Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin, who was a part of SNCC and the Black Panther Party before his disenchantment. He was introduced to the political philosophy of anarchism in prison. Becoming an articulate advocate of it, he went on to write this book while still imprisoned. Handwritten in 1979 in secret, its pages had to be smuggled out in order to be published. It has become an important touchstone for Black anarchism and remains a relevant critique. Next, in “Black Dignity: The Struggle Against Domination” (2022), theologian Vincent Lloyd, looking to contemporary Black liberation movements, re-conceptualizes dignity as performance or praxis and goes on to redefine Black dignity as “struggle against domination” (15). Lloyd then makes his case by exploring through each chapter key aspects to Black dignity: Black rage, Black live, Black family, Black futures, Black magic, and a political orientation of revolution. The final book, “Black Liturgies: Prayers, Poems, and Meditations for Staying Human” (2024) by Cole Arthur Riley, is a spiritually-oriented work that was just published two months ago. This book began, however, on social media in 2020 during the Black Lives Matter resurgence around the death of George Floyd and so many others. As she describes, “I was desperate for a liturgical space that could center Black emotion, Black literature, and the Black body unapologetically. I began sharing poetry and prayers and quotations on social media” (xvi). This book represents the culmination of those years of deep reflection and sharing. As she explains, “The liturgy that I’ve found healing in happens to be written liturgy. For me, reimagining written prayer outside of the white gaze has been a practice in both liberation and solidarity. Something striking happens when you are made to read words written in particularity, with a shared voice” (xvii). Ramadan 9

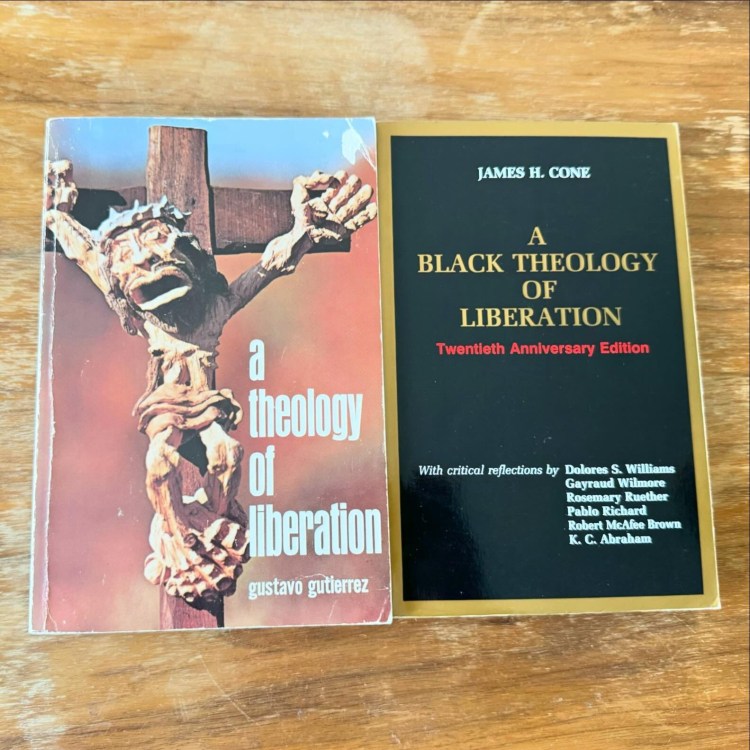

Ramadan 10

I would be remiss to omit works of liberation theology from a list on the topic of liberation. I share here two foundational works in the field of Christian liberation theology. First is Gustavo Gutierrez’s “A Theology of Liberation” (1983), originally published in 1971 in Spanish and then translated into English in 1973. Working alongside other Latin American theologians, Gutierrez, a Dominican priest, developed a theology rooted in scripture and attentive to the lived socio-economic realities of Latin America. He writes, “This is a theology which does not stop with reflecting on the world, but rather tries to be part of the process through which the world is transformed. It is a theology which is open – in the protest against trampled human dignity, in the struggle against the plunder of the vast majority of people, in liberating love, and in the building of a new, just, and fraternal society – to the gift of the Kingdom of God” (15). Alongside it is another incredibly important work, “A Black Theology of Liberation” (2001), which was first published by James Cone in 1970. In the original preface Cone states, “In a society where persons are oppressed because they are black, Christian theology must become black theology, a theology that is unreservedly identified with the goals of the oppressed and seeks to interpret the divine character of their struggle for liberation” (v). While unquestionably significant, the works to have emerged since them have been manifold and brilliant. Ramadan 10

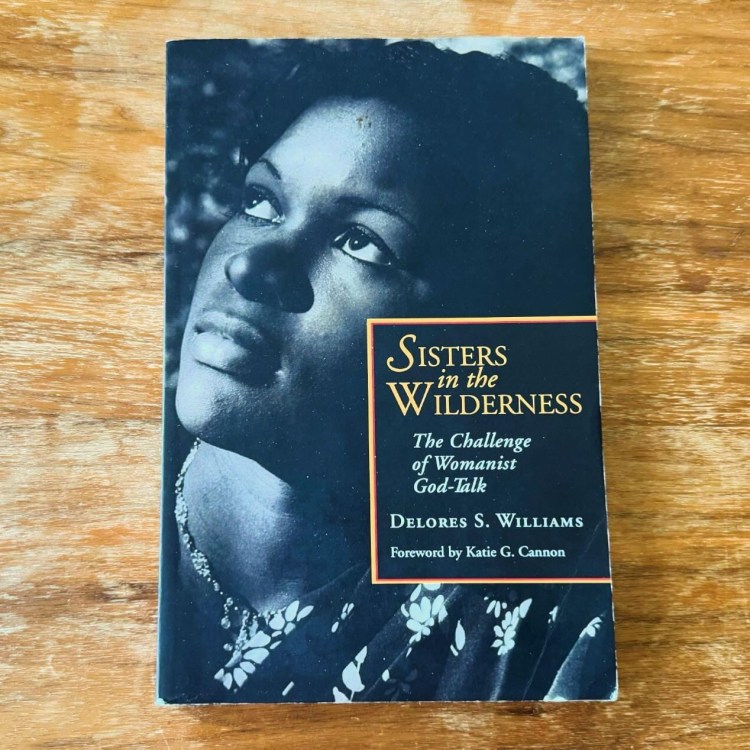

Ramadan 11

I share today another theological classic, Delores S. Williams “Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk,” which focuses on the biblical Hagar. While this anniversary edition appeared in 2013, the book was originally published in 1993 to much acclaim. I’ve recently reflected and written on the honored figure of Hagar in Islam, who although “muted” in the Qur’an is very much stunningly present in the ritual lives and religious memories of Muslims. I am, of course, indebted to others who have dwelled long on Hagar before me and done so with profundity. Among those is Williams who powerfully and poignantly ties the biblical story of Hagar to the contemporary experiences of African-American women surfacing, in the process, matters of race, belonging, motherhood, and freedom. She then turns to developing the theological language that emerges from this nexus. At the end of the first chapter Williams writes, “The African-American community has taken Hagar’s story unto itself. Hagar has ‘spoken’ to generation after generation of black women because her story has been validated as true by suffering black people. She and Ishmael together, as family, model many black American families in which a lone woman/mother struggles to hold the family together in spite of the poverty to which ruling class economics consign it. Hagar, like many black women, goes into the wide world to make a living for herself and her child, with only God by her side” (31). Ramadan 11

Ramadan 12

“She Who Struggles: Revolutionary Women Who Shaped the World” (2023) is a brilliant collection edited by historians Marral Shamshiri and Sorcha Thomson. Over the course of thirteen chapters, different scholars profile a host of 20th and 21st-century women deeply involved in revolutionary struggles and liberation movements of their time, place, and beyond. The coverage is impressive and the spotlight needed. For instance, Chapter Four is the recorded testimony of Jehan Helou, a Palestinian woman who travelled the world to collaborate and learn from fellow liberation movements. Chapter Five offers a look into the life of Shigenobu Fusako, who led the Nihon Sekigun or “Japanese Red Army” that took direct action in support of Palestinian liberation, including the bloody attack at Lod Airport. Chapter Seven turns to Vietnamese women and their symbolic invocation by Palestinians and Iranians in their respective liberation struggles. As authors Thy Phu, Le Espiritu Gandhi, and Donya Ziaee document, “Despite US foreign policy objectives, connections between northern Vietnamese leaders and Palestinian liberation fighters flourished through independent circuits of solidarity. Flouting a Cold War logic of containment, Palestinian and Vietnamese militants highlighted points of connection between their movements, drawing rhetorical and visual parallels between their goals of anti-imperialist national liberation” (117). Many others are featured within this worthwhile volume of remarkable lives. Ramadan 12

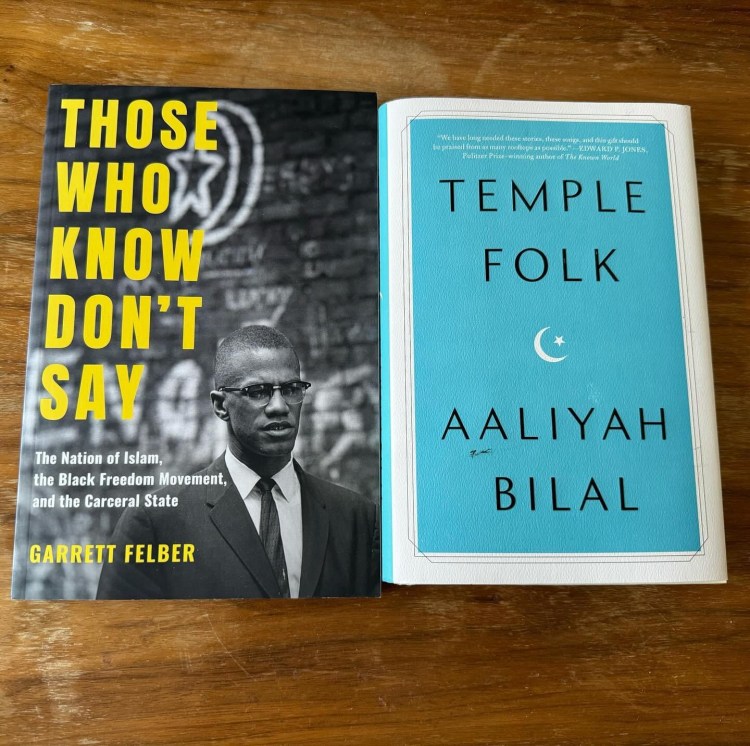

Ramadan 13

The Nation of Islam is often not given the attention or credit that it deserves. Here are two quite different works that center the experience and activity of the Nation in their own ways. First is an important academic study, Garrett Felber’s “Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement, and the Carceral State” (2020), which documents and analyzes how the Nation engaged with police, prisons, and the legal system primarily during the 1950s, 60s, and early 70s ending with the 1971 Attica rebellion. It also interrogates the ways that the carceral state responded to the work of the Nation and other Black struggles, which involved a reconfiguring – or disfiguring – of narratives. Here is the opening to Chapter 1: “During the summer of 1942, after the forced removals and mass imprisonment of Japanese Americans in the western United States, the FBI and police arrested eighty African American ‘admirers’ of Japan in Chicago, with the FBI claiming that the Nation of Islam was receiving military equipment from Japanese spies. Among them was Elijah Muhammad, who had been arrested once that summer for draft evasion. He was held for over a month on a $5,000 bond before thirty Muslims wearing ‘red buttons showing a ‘mystical’ white crescent… [with] turbans of varying colors worn by women and crescent rings on the hands of the men’ surrounded the jail for fourteen hours, demanding that they, too, be put in prison for draft evasion” (16). Alongside this book is the relatively recently published “Temple Folk” (2023) by Aaliyah Bilal. “Temple Folk” is a collection of ten short stories imaginatively centered on the lives of Muslim members of the Nation of Islam. Through these brief, but memorable fictional windows the Nation of Islam and the human experiences of its members are brought vividly to the fore in a way all too rarely tread. Ramadan 13

Ramadan 14

I’m indebted to Nabila Munawar for my first proper introduction to Stuart Hall. Perhaps being on this side of the Atlantic focused my attention elsewhere, much to my detriment. In any event, Hall, who was a monumental public intellectual and scholar of sociology in the UK, had been invited in 1994 to Harvard University to deliver the W.E.B. Du Bois Lectures. The resulting volume “The Fateful Triangle: Race, Ethnicity, Nation” (2017) was published many years later based on transcripts and Hall’s own lecture notes taken from that three-part lecture series. As I think through difference, race, and space, I have found Hall an incredibly productive interlocuter. His thinking here is built and layered across so many pages, so it was challenging to find a good quotable passage even if this particular work is a fairly accessible entry point. Here, though, is one striking excerpt: “Diasporas are composed of cultural formations which cut across and interrupt the settled contours of race, ethnos, and nation. Their subjects are dispersed forever from their homelands, to which they cannot literally return. Being the product of several histories, cultures, and narratives, they belong to several homes most of them at least in part symbolic – that is to say, imagined communities – to which there can be no return. This means that to be the subject of such diaspora is to have no one particular home to which one belongs exclusively” (172). This one is for all of us living this increasingly prevalent diasporic reality. Ramadan 14

Ramadan 15

Here are two monumental voices in the struggle for liberation, Frantz Fanon and James Baldwin, and both of these books are part of a biographical series called “Revolutionary Lives” from Pluto Press. “Frantz Fanon: Philosopher of the Barricades” (2015) by Peter Hudis offers a concise, but sweeping overview of the psychiatrist and philosopher from Martinique who would go on to write pivotal works like “Black Skin, White Masks,” based greatly on his experiences in France, and “The Wretched of the Earth,” born out of his dedicated efforts in support of the Algerian Revolution. Next to it is “James Baldwin: Living in Fire” (2019) by Bill V. Mullen, which brings together a compelling narrative of Baldwin’s life that is attentive to his broad literary contributions while also tracking his engagement with various people and groups, like the Black Panther Party, through major stages of his life. Because I’ll have more to say on Baldwin tomorrow, here is an excerpt from Hudis’s introduction to the Fanon biography: “The specter of Fanon has returned, and largely because he was one of the foremost thinkers of the last century on race, racism, and human liberation. It is precisely because we are not past the racism of the last century that we are not past Fanon: instead, we seem to be colliding into him, all over again. In doing so, what will we find?” (4). Ramadan 15

Ramadan 16

James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time,” originally published in 1962, is a work I find myself continually revisiting given how memorable, meaningful, and resonant his words remain. The book consists of two pieces: “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation” and “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region of My Mind.” For those interested in Islam, he recounts in his compellingly poetic way his meeting with Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam in the latter piece. Here is a different excerpt from the “Down at the Cross”: “Time catched up with kingdoms and crushes them, gets its teeth into doctrines and rends them; time reveals the foundations on which any kingdom rests, and eats at those foundations, and it destroys doctrines by proving them to be untrue” (51). This seems apt for our times. Then, in his letter to his nephew, the piece I find myself revisiting regularly, Baldwin writes of white people: “The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them. And I mean that very seriously. You must accept them and accept them with love. For these innocent people have no other hope. They are, in effect, still trapped in a history which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it. They have had to believe for many years, and for innumerable reasons, that black men are inferior to white men. Many of them, indeed, know better, but, as you will discover, people find it very difficult to act on what they know. To act is to be committed, and to be committed is to be in danger. In this case, the danger, in the minds of most white Americans, is the loss of their identity… we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it” (8-10). Ramadan 16

Ramadan 17

At this point, Omar ibn Said has been a significant figure in most historical narratives of Islam in America and his autobiography has been available for some time. Nonetheless, this work by Mbaye Lo and Carl W. Ernst, “I Cannot Write My Life: Islam, Arabic, and Slavery in Omar ibn Said’s America” (2023) goes a long way to better contextualizing and complicating our understanding of Omar and his textual legacy. First, the authors translates all eighteen of the extant Arabic texts that Omar left behind, many of which are brief, yet striking. The translations are also extensively annotated to trace the scriptural and religious sources upon which Omar was drawing. Additionally, his writings are analyzed across a series of chapters that powerfully bring to the fore the broader contexts from which Omar emerged and in which he struggled throughout his years – life in Senegambia, the blackground of his enslavers, the suppressive supremacist culture of the American South, and the blinding zeal of Christian missionaries with their eyes set on Liberia in particular and Africa at large. Finally, Lo and Ernst convincingly challenge the claims made by many about Omar’s supposed conversion to Christianity. At the outset, they state, “We argue, in this book, that Omar’s writings were systematically distorted, ignored, and denied by the defenders of racism, slavery, and white supremacy,” (5) and then proceed to develop an argument based on the surviving textual record. Omar, in an 1819 letter to the Owens who had kept him enslaved, writes, after many scriptural and pious invocations, “I want to be seen in our land called Africa, in the place of the river called Kaba” (82). Although he would never fulfill this desire, dying in North Carolina in 1864, his testament is finally being heard in our lifetimes. Ramadan 17

Ramadan 18

Alex Lubin’s “Geographies of Liberation: The Making of an Afro-Arab Political Imaginary” (2014) is a capacious political history seeking to “uncover the making of a political imaginary across and beyond the nation-state that has united questions of Jewish diasporic politics, black internationalism, and Palestinian exile” (4). Discussed in its pages are the likes of Dusé Mohamed Ali, W.E.B. DuBois, his son David Graham DuBois, and Huey Newton. It ranges historically from the American decades after the Civil War through the end of European colonialism in the Middle East and then up to the challenging nation state realities of the present. In one chapter, the author explores the relationships that developed between the Black Panthers and the PLO with a final section focused on the Israeli Black Panthers that was formed by Mizrahi Jewish youth. On this matter Lubin writes, “Many Jewish groups took the Panthers to task as an anti-Semitic organization. What gets lost in this criticism, however, is how the Black Panthers intercommunal politics reverberated in unexpected contexts. Throughout the period that the Black Panther Party formulated an anti-imperialist argument about Israel, and formed solidarity with Palestinians, its intercommunal politics were influencing a group of Israeli Jews for whom the Panthers’ analysis of racial capitalism was especially relevant” (130). Ramadan 18

Ramadan 19

Here is a work that was published quite recently that strikes me as an important touchstone for future scholarship. “Medina by the Bay: Scenes of Muslim Study and Survival” (2023) is a engrossing work by Maryam Kashani that powerfully and critically relates the histories and lived experiences of Muslim communities in the San Fracisco Bay area. This analysis attentive to race, space, and knowledge formation is delivered through a series of captivating narratives that are stitched together by periodic cinematic scenes, which Kashani theorizes in the introduction as the “ethnocinematic.” Known names, like Zaytuna and the Black Panther Party, as well as familiar Muslim controversies and tensions appear throughout, but the work is not merely a focused study on Muslim life in the Bay area. It works to do more. As Kashani explains, “Rather, I propose that through the (micro) lens of one diverse ‘community,’ “Medina by the Bay” provides an alternative view of the (macro) socioeconomic and cultural dynamics of the Bay Area in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries and poses a question more broadly about how we think and act ethically and politically about knowledge and survival” (13). To that end, what Kashani unearths across the span of this work is a paradigm of praxis and liberation born from out of Muslim ways of knowing and being. Ramadan 19

Ramadan 20

Sohail Daulatzai and Junaid Rana have collected in “With Stones in Our Hands: Writings on Muslims, Racism, and Empire” (2018) a remarkable collection of essays aimed at engaging the structures of oppression we face today. Although published six years ago, the volume still speaks to our moment. For example, there are quite a number of compelling and important pieces on Palestine that are worth (re)reading in light of the catastrophe being meted out there now. Yet, that is not all. The collection is rich with critical perspectives and ranges widely over many contexts of concern – something sorely needed given the array of subjugating forces at work today. The editors provide this framing in the volume’s introduction, “While not all those in this volume would necessarily agree with what we call the Muslim Left and the Muslim International, there is an undeniable force, a momentum, that is organized in terms of opposition and dissent. The Muslim Left and the Muslim International most immediately reference a radical history of critique and protest that imagines another world in line with struggles for social justice, decolonial liberation, and global solidarity” (x). Ramadan 20

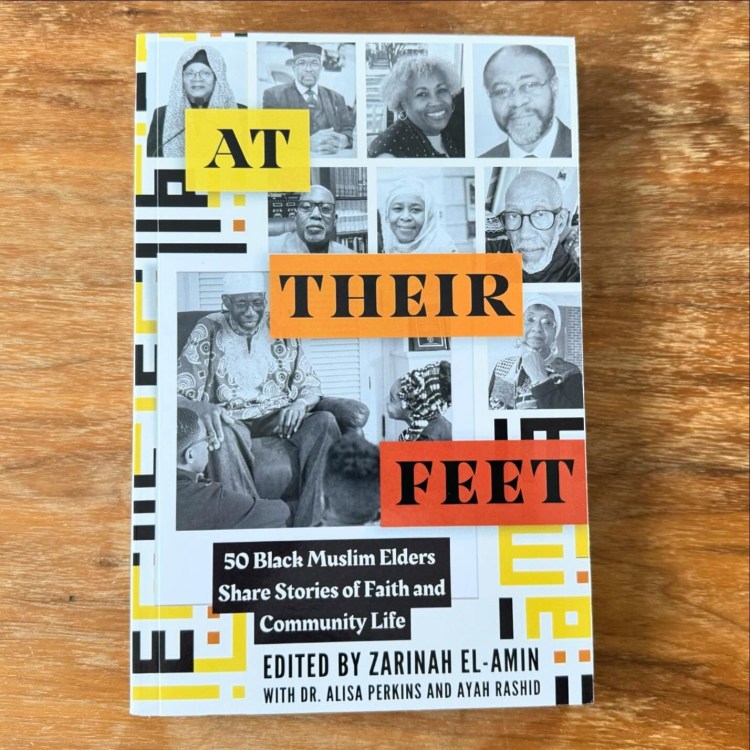

Ramadan 21

I have always been especially inclined to oral histories. They allow voices that might otherwise be overlooked or unheard to carve a space into our consciousness and then do the needed work upon our everyday ethics. Adding to the two oral history works I shared earlier this month, here is a third that transports us to a different, but no less important context. It gathers together the work of its editors Zarinah El-Amin, Alisa Perkins, and Ayah Rashid and builds, in part, upon the Detroit Storytelling Project. “At Their Feet: 50 Black Muslim Elders Share Stories of Faith and Community Life” (2022) covers some of those who lived in Detroit but encompasses the experience of many others across the United States. The book was prompted by the death of El-Amin’s mother, Dr. Cheryl El-Amin, and the desire of her father, Imam Abdullah El-Amin, to preserve some of his wisdom for his community. While there are many lives that I could feature here, I’ll share an excerpt from a respected elder in our local community, who is no less active nationally (as with The Islamic Seminary of America), Dr. James Jones. He shares, “During my time at Hampton, I rant into a guy named Stokely Carmichael, who introduced me to a concept I had never heard of before: Black Power. I had always thought about integration as being the way up and forward in society. During Stokely Carmichael’s talk at Hampton, he asked if we had read several specific books. One of them was the ‘Autobiography of Malcolm X.’ I went on to read it right away, and it was a life-changing experience. I realized that education was at the center of Malcolm X’s transformation. Malcolm X turned his life around by reading a great deal while in prison; he read the dictionary, learned new words, and acquired a vocabulary that would help him hold his own when he debated at places like Oxford University. I began thinking about changing the world” (136-137). May our commitment to knowledge allow us to do likewise. Ramadan 21

Ramadan 22

I was first introduced to Black revolutionary Safiya Bukhari through a fantastic conference presentation by Iman Abdoulkarim, whose current research focuses, in part, on the remarkable life and work of Bukhari. “The War Before: The True Life Story of Becoming a Black Panther, Keeping Faith in Prison & Fighting for Those Left Behind” (2010) is a posthumous collection that brings together the words that Safiya Bukhari left behind. Bukhari led an extraordinary life that had her working alongside the Black Panther Party, Yuri Kochiyama, political prisoners, the Republic of New Afrika, among many others. After her death, her daughter Wanda Jones approached Laura Whitehorn to have Bukhari’s papers collected and edited for the present volume. Included are articles, essays, notes, and interviews as well as an opening autobiographical sketch. In a second afterword from 1994 to that last piece, Bukhari wrote: “Today, this minute, this hour (as Malcolm would say), I have come to realize that picking up the gun was/is the easy part. The difficult part is the day-to-day organizing, educating, and showing the people by example what needs to be done to create a new society. The hard painstaking work of changing ourselves into new beings, of loving ourselves and our people, and working with them daily, to create a new reality – this is the first revolution, that internal revolution” (13). Ramadan 22

Ramadan 23

Given the state of our world, it is unsurprising that the problem of evil continues to capture our attention. Our increasing interconnectedness with one another has certainly made how we experience and witness suffering more acute. It came as no surprise, then, that I was asked to review two new books on the nature of evil that were published earlier this year. While I haven’t found the time yet to complete my reading of either, it felt appropriate in these times to share something about them here. The first work is Salih Sayilgan’s “God, Evil, and Suffering in Islam” (2024), which explores from a concertedly theological lens the problem of evil. Nonetheless, there seems to be a distinct attentiveness to comparative religion as he proceeds through his subject matter, helpful for those coming from outside the Islamic tradition. In the course of the work he explores perennial problems like illness, aging, death, and disability before concluding with contemporary concerns like climate change and the coronavirus pandemics. Appearing alongside it is Amir Saemi’s “Morality and Revelation in Islamic Thought and Beyond: A New Problem of Evil” (2024). This works takes a much more philosophical approach by posing that a “new problem” now exists with respect to the seemingly prescribed evils named in Scripture, like the account of Moses and Khidr in surat al-Kahf (Q. 18) and the sacrifice asked of the Abraham and our personal moral judgements. Saemi divides the book in two parts with the first part dedicated to the classical positions that place “Scripture first,” before moving on to second part in which ethics takes priority. The concern in this endeavor is coming to terms with how Muslims can still maintain their independent moral judgements when revelation seems to contravene it in certain cases. Based on my cursory overview alone, I’m looking forward to reading each more carefully in the days ahead, insha’Allah. Ramadan 23

Ramadan 24

Here are two voices offering distinctive Muslim visions of liberation. Ali S. Harfouch argues for a radical critical consciousness born out of the Islamic concept of tawḥīd and a new metaphysical consciousness in “Against the World: Towards an Islamic Liberation Philosophy” (2023). There is a clear call for us to learn from those on the “periphery,” so to speak, as he discloses at the end of this slim volume, “In a Muslim world, in the throes of transition and in a world characterized by an emergent and critical consciousness, the Islamic movement and the Muslim thinker must seek out those on the margins of the Muslim world, those who are most critical of the world-order having faced the brunt of its oppressive dispositions” (109). In “Islam and Anarchism: Relationships and Resonances” (2022), Mohamed Abdou makes a sustained case for an Islamically-centered anarchism, or “Anarcha-Islam” to challenge the entrenched structural disparities in the world. In his conclusion he writes, “Every oppression we have internalized is intimately entwined with a plethora of other oppressions and social justice concerns, and in the absence of their overcoming we will forever remain incapable of achieving true liberation. For diasporic Muslims in Turtle Island as well a majority of Muslim in Egypt, this entails a discussion of how we interpret our double-conscious identities. As Muslims we need to ethically-politically associate our identities with a communal sense of responsibility towards the Other. Collectively, leftists and Muslims need to re-establish boundaries between the realms of the private (khuṣūṣiyāt) and public (ʿumūmiyāt) that have eroded if not withered away globally. That is, if we truly seek to found a non-racialized, global, Muslim Umma that embodies the spirit of the Medina Charter, and hence includes non-Muslims and orbits around decolonial tenets of social justice” (229). Ramadan 24

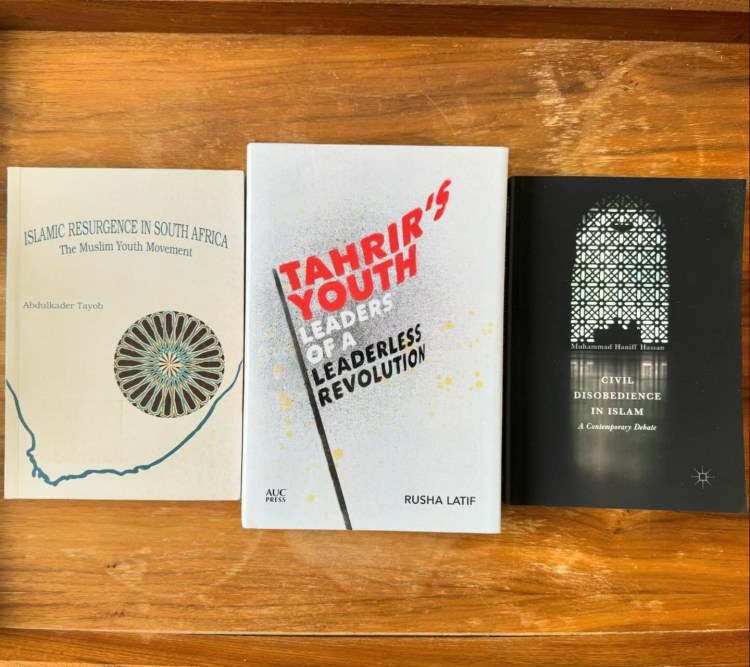

Ramadan 25

I’m sharing today three books that explore resistance in different contexts and from different vantages of concern. The first is an older work, “Islamic Resurgence in South Africa: The Muslim Youth Movement” (1995) by Abdulkader Tayob. Published shortly after the end of apartheid in South Africa, Tayob provides important context for the Muslims of the country before offering a close look at the work of the Muslim Youth Movement specifically. He covers its history from its founding in 1970 while tracing the Islamic thought and principles undergirding it, changes and all. Alongside this work is Rusha Latif’s “Tahrir’s Youth: Leaders of a Leaderless Revolution” (2022). Moving to the events surrounding the January 25 Revolution in 2011 and shifting to the context of Egypt, Latif offers a compelling study of another group of young people that were deeply engaged with organizing during this critical time in the nation. Sharing their own words and offering her careful analysis, we are provided a rare window into how the leaders of the Revolutionary Youth Coalition (I’tilaf Shabab al-Thawra) negotiated the shifting dynamics of that tumultuous time. Finally, comes “Civil Disobedience in Islam: A Contemporary Debate” (2017) by Muhammad Haniff Hassan. Also written in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, this works takes a decidedly different approach by focusing on the various legal opinions expressed by the religious scholars in the region in response to the mass protests and acts of civil disobedience that were emerging. There are critical lessons to be learned from these past episodes, I believe, that would benefit us as we navigate the many challenges confronting us today. Ramadan 25

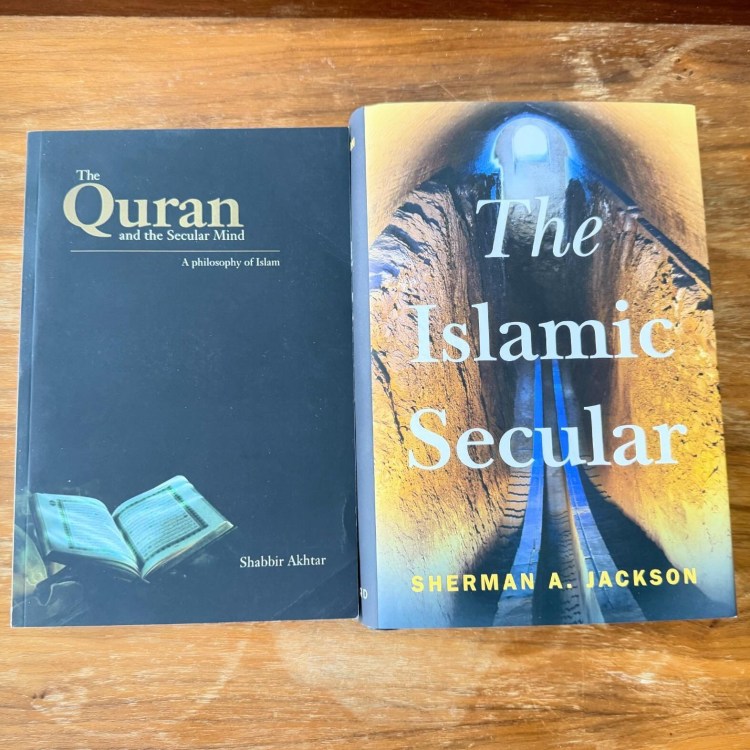

Ramadan 26

The works shared today, substantial 400 page tomes, serve as a kind of tribute. They are both concerned, moreover, with challenging Western secularism in their own ways. Last year, on July 23, 2023 the Muslim philosopher Shabbir Akhtar passed away. He was a prodigious scholar whose writings I saw as important for the sort of work that I’m pursuing now. Moreover, one of his more recent books “The Quran and the Secular Mind: A Philosophy of Islam” (2008) had been repeatedly recommended to me by several different friends, but I had kept putting off picking it up. When the news of Akhtar’s sudden death broke last summer I realized it was time to turn to it at last. Akhtar states, “In this work, I counsel modern Muslims, as intelligent and reflective heirs of their faithful tradition, to establish a philosophy of Islam, in an analytical idiom” (2). Then, after hundreds of pages he concludes his book with his “Preface to a philsophy of Islam.” Alongside this work, is the latest publication from a scholar whose books have been deeply influential for my own theological turn. In “The Islamic Secular” (2024) Sherman Jackson discloses the aim of his book early in the introduction: “Part of my aim in the present project is to reverse the effects of the Islamic Secular’s exclusion not only from the intepretative prism through which the West has studied Islam but also from that of modern Muslims – an exclusion that has brought the latter to a similarly dichotomous understanding of the relationship between the religious and the secular, which ultimately sustains the power and primacy of the Western secular/religious divide in favor of the secular” (11). I am eager to explore the contents of both. Ramadan 26

Ramadan 27

These past days I’ve featured the works of substantial and accomplished scholarly voices. All too often, however, the voices on the ground are overlooked, even though the heart of the work of liberation happens where they are, well outside the confines of academia. I am glad to share, then, “Shaping Muslim Futures: Youth Visions and Activist Praxis” (2021) by Sameena Eidoo. At the outset, the author explains, “For we Muslims to project ourselves into the future is a radical act, especially in a world where the lives of Muslims and those perceived to be Muslim have been and continue to be threatened. [This book] is a guidebook that weaves narratives of activist Muslim youth situated in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), Ontario, Canada, shaping their desired futures, and creates space for readers to clarify their own. Guided by an unwavering belief in the possibility of collective liberation, ‘Shaping Muslim Futures’ is designed to facilitate exploration of alternative futures” (1). Eidoo incorporates the earnest words of these young Muslims throughout the span of the book as they struggle to change their communities for the better. Here is an except from Karim concerning his engagement with the Toronto Community Housing Corporation: “I wanted life to be different. We seem so forgotten. In my neighborhood, there are drugs everywhere and shootings every so often. I felt like there had to be something to do to help people out… I would like to influence those in positions of authority and give them a different perspective on youth in communities” (58). May we learn to listen to every voice and story. Ramadan 27

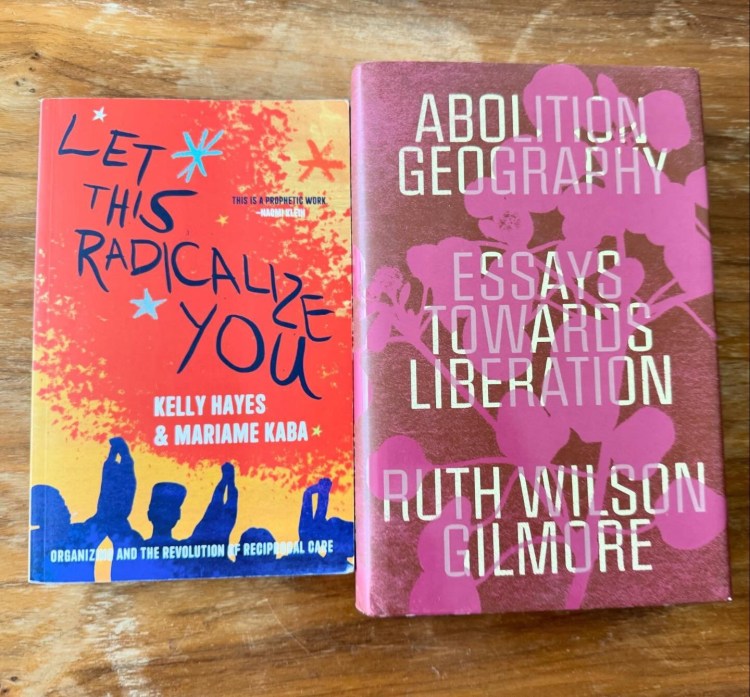

Ramadan 28

Touched on in a previous Ramadan, I return to Mariame Kaba whose words and work I have greatly admired. Kaba with fellow organizer Kelly Hayes published “Let This Radicalize You: Organizing and the Revolution of Revolutionary Care” (2023) last year. Drawing upon the wisdom of a lifetime in community organizing and collective action (that remains ongoing), the authors have provided an inspiring guide for all of us who feel called to engage while also building community. On the topic of building broader movements they write: “Drawing connections between struggles, rather than making comparisons, also lends itself to empathy, which is essential in our work. Organizers help people understand their own social and historical position in relation to other people, which means reframing their own history and the histories they know in relation to other histories and experiences. When we organize people, we are inviting them to relate to others. We are also reminding them, or perhaps telling them for the first time, that their fate, their liberation, and their particular social concerns do not exist in any kind of singularity. Individualism has programmed people to view our fates and histories as divided. Movement education is, in part, a deprogramming process. It is a path toward unlearning mythologies and liberating ourselves from the isolation of individualism and enclosed narrative” (105). Then, in Chapter 4 “Think Life a Geographer,” Kaba and Hayes draw on the work of Ruth Wilson GIlmore, who I am placing alongside their work. While I haven’t properly begun it yet, I am eager to learn what Gilmore shares in the many pieces included in “Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation” (2022). Ramadan 28

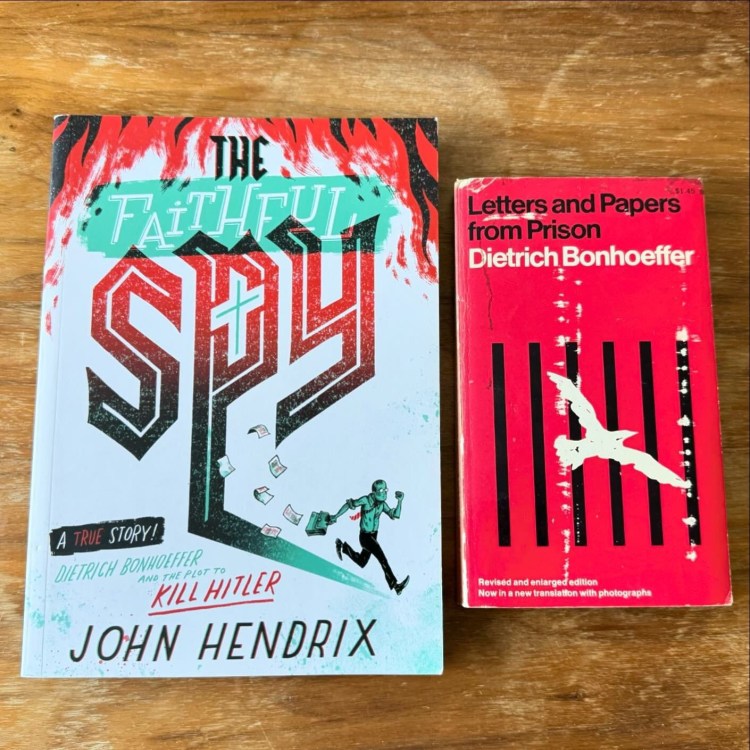

Ramadan 29

Today is the day of the solar eclipse for many of us here, a time when the sun shall be darkened before our eyes and night shall momentarily descend. Tomorrow marks the 79th anniversary of the death of German theologian and Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer. After a remarkable life of faith, he was hanged on April 9th, 1945 by the collapsing Nazi Regime. For these two reasons, I wanted to feature Bonhoeffer today. For those unfamiliar with him, I would recommend this accessible introduction, “The Faithful Spy” (2018) a graphic novel by John Hendrix. It relates how from an early age Bonhoeffer was committed to God and the work of theology recounting in particular how influential his short time in America was: studying at Union Theological Seminary, experiencing the Black Church, and developing a commitment to nonviolence. The work then documents the rise of Hitler and the moral conflict that it precipitated for Bonhoeffer. Eventually, he felt called to join a conspiracy to assassinate the Führer. Bonhoeffer is quoted as saying, “The ultimate question for a responsible man to ask is not how much he is to extricate himself heroically from the affair, but how the coming generation is going to live” (157). The conspirators ultimately failed, despite three attempts, and in the midst of it all Bonhoeffer was arrested. The second book, “Letters and Papers from Prison” (1967) collects many of the poems, writings, and letters that he managed to compose during that time. Then, as Germany withered before the advancing Allies, Bonhoeffer was executed. The order for his death came the day before (today). A poem that Bonhoeffer wrote the summer prior closes the book:

“God, who dost punish sin and willingly forgive, I have loved this people.

That I have borne its shame and burdens, and seen its salvation – that is enough.

Seize me and hold me! My staff is sinking; O faithful God, prepare my grave” (225-6). Ramadan 29

Ramadan 30

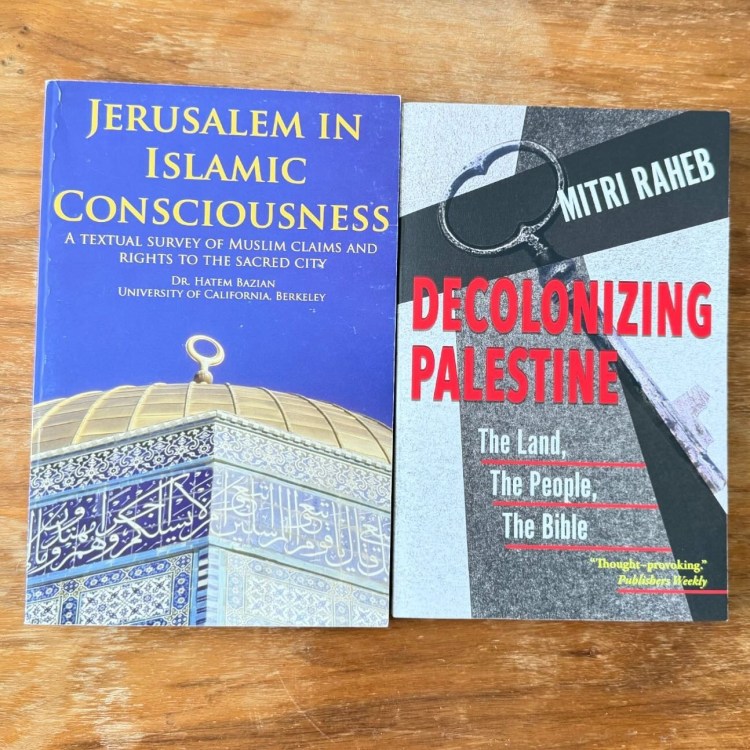

We are in the last day of Ramadan and the brutal campaign of devastation remains ongoing in Gaza. We have witnessed the horrors there for six months – half a year – at this point. It feels appropriate – or needed rather – to share two theological works committed to the liberation of Palestine. The first was published some time ago but remains relevant now. “Jerusalem in Islamic Consciousness: A Textual Survey of Muslim Claims and Rights to the Sacred City” (2006) by Palestinian American scholar Hatem Bazian carefully documents how Muslims throughout the centuries have understood the religious significance of the city by working through a wide range of Qur’anic passages, prophetic narratives, and other religious accounts. The book provides a helpful foundation for further critical reflection. Alongside this work is a book that has been recommended to me from many quarters. After hearing of its accolades, I have just acquired, “Decolonizing Palestine: The Land, the People, the Bible” (2023) by Mitri Rehab, a Palestinian Christian based in Bethlehem. While I have yet to dive into it, here is an excerpt from his introduction: “This book is a first attempt to bring settler colonial theory in dialogue with Palestinian theology. It is an exercise in the further development of a contextual and decolonial Palestinian Christian theology that addresses settler colonial theories. It is a wake-up call for people interested in Israel/Palestine to recognize the reality on the ground, to reflect critically and prophetically on the scripture, and to engage in a new paradigm. It is a wake-up call to perceive how the prevailing exclusive nationalist and expansionist ideologies are disguised in biblical language and motives. My hope is that this new paradigm shift will bring us closer to justice and closer to the spirit of God” (x). May God’s justice and mercy overwhelm this world and transform us all rightly. Ramadan 30

Eid

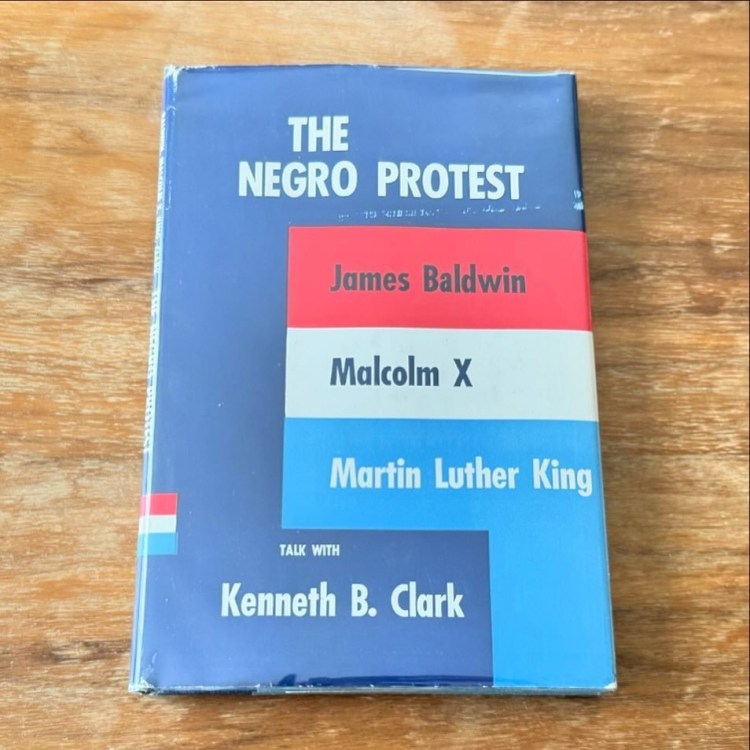

I thought it fitting to end with a look back at three icons of liberation as varied as their views may be. This is “The Negro Protest: James Baldwin, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Talk with Kenneth B. Clark” (1963) published while all three of these luminaries were still alive. Kenneth Clark interviewed each of them for National Education Television in 1963. These are the transcripts of those exchanges. While the interviews are wide-ranging, a common refrain appears: protest and the place of violence and nonviolence. For his part King offers, “I think that non-violent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom and human dignity. It has a way of disarming the opponent. It exposes his moral defenses. It weakens his morale and at the same time it works on his conscience. He just doesn’t know how to handle it and I have seen this over and over again in our struggle in the South” (39). Baldwin remarks, “…the Negro has never been as docile as white Americans wanted to believe. That was a myth. We were not singing and dancing down on the levee. We were trying to keep alive; we were trying to survive a very brutal system. The Negro has never been happy in ‘his’ place. What those kids first of all proved – first of all they proved ‘that.’ They come from a long line of fighters. And what they prove… is not that the Negro has changed, but that the country has arrived at a place where he can no longer contain the revolt” (10). Finally Malcolm X declares, “Any Negro who teaches other Negroes to turn the other cheek is disarming that Negro. Any Negro who teaches Negroes to turn the other cheek in the face of attack is disarming that Negro of his God-given right, his moral right, of his natural right, of his intelligent right to defend himself. Everything in nature can defend itself, and is right in defending itself except the American Negro” (26). This is but a snapshot of their thinking in 1963. Nonetheless, they are words we should still dwell upon in our troubled times. May we experience liberation within our lifetime and within our lives. May this day and the days ahead be blessed for us all. Eid Mubarak.