This year I open with the latest books concerning Malcolm X, but then let the month wend its way through a variety of works and topics before ending back with Malcolm once more. It felt appropriate to do so since 2025 would have marked his 100th year of life. Back to the MRB.

End of Sha’ban

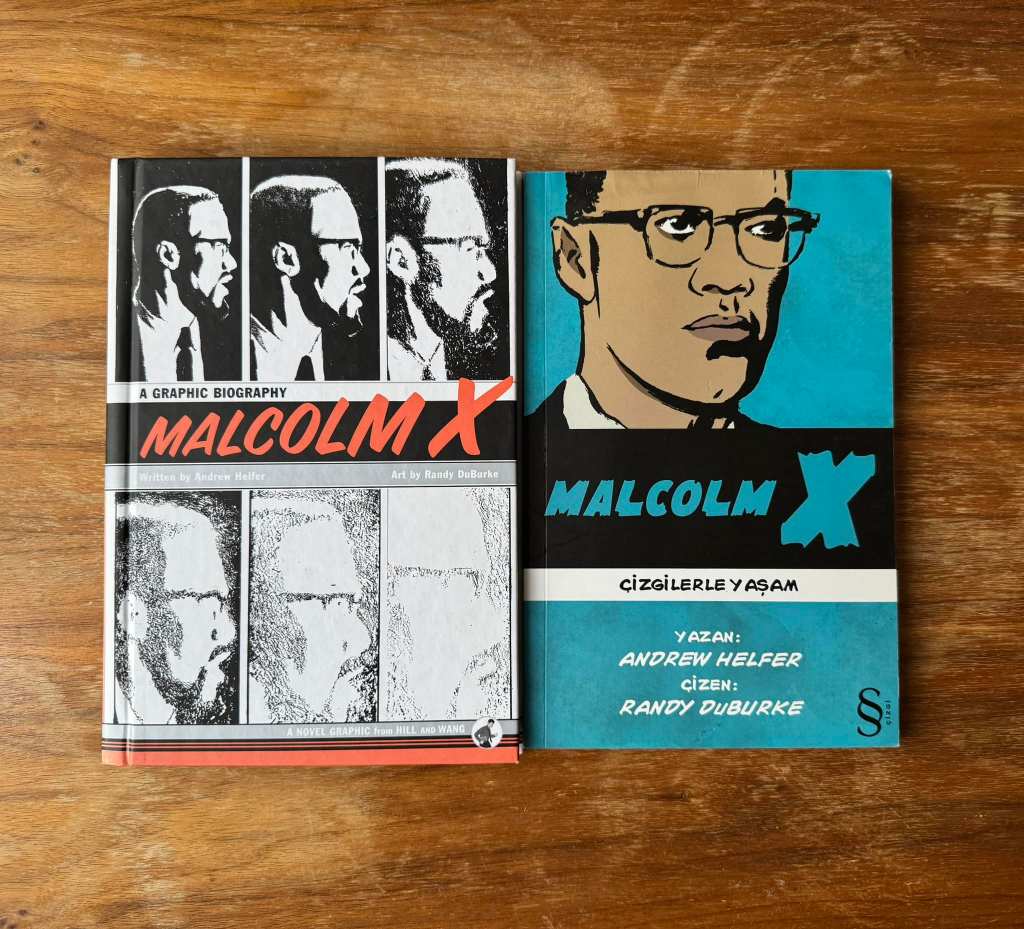

Time seems in short supply this year, far more so than in years past. Nevertheless, the month of Ramadan is approaching and I’m working to keep the bookshare tradition alive. As in years past, my intention is to share at least one book a day for the entire month of Ramadan. You can see the work of preparation in action, but to prime the stream of works to come, I wanted to attend to some unfinished business. Specifically, I wanted to share a work I had been looking for before but couldn’t find at the time. It is also proved to be an appropriate beginning to this undertaking since this year marks the 60th year since Malcolm X’s passing and later in May we’ll celebrate what would have been Malcolm’s 100th year with us. What do I have in mind? Two years ago I dedicated the entire month of Ramadan to works by or about Malcolm X. On day 24 I featured the one you see on the left, “Malcolm X: A Graphic Biography” (2006) written by Andrew Helfer and illustrated by Randy DuBurke. At the time I recalled having a Turkish translation that I had picked up in Istanbul, but couldn’t find it then. I only recalled that it was water damaged. In the intervening two years, that copy has resurfaced with the damage far less severe than I expected. Here it is: “Malcolm X: Çizgilerle Aṣam” (2009) as translated by Sabri Gürses. This is just the beginning, of course. More to come, on Malcolm especially, in the days ahead insha’Allah. On the Eve of Ramadan

Ramadan 1

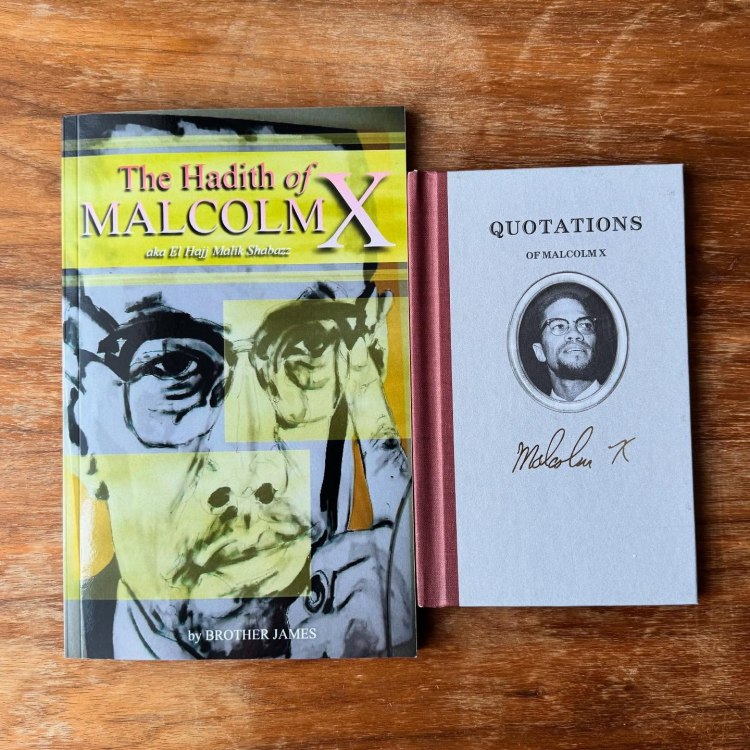

Between last year and this a number of works on Malcolm X have been added to the shelves, some of which are older works that I had overlooked, and others more recently published. I share today two works of each type, yet both dedicated to perserving and honoring Malcolm’s words. “The Hadith of Malcolm X, aka El Hajj Malik Shabazz” is edited and independently published by, quite cryptically, a Brother James. Little else is intentionally disclosed about the compiler. His use of the term “hadith” is arresting, yet its explanation is more benign – by it he means “the daily utterances of.” The book pulls quotes from a variety of sources, like the autobiography and his speeches, but also include excerpts from his FBI file as well as James Cone’s “Martin & Malcolm & America.” An attempt is made to divide the sayings by subject, but it remains a challenge to navigate even with its modest size. The other slim volume, “Quotations of Malcolm X” is a pocket-sized hardback from Applewood Books. Its production quality is, unsurprisingly, more professional and polished. With no compiler attributed, the book does a fine job of drawing from a wide range of sources while also providing clear and dateable citations for each quotation. Unfortunately, it weighs in at a modest 32 pages and does not seem to be organized in any particular fashion. Ramadan 1

Ramadan 2

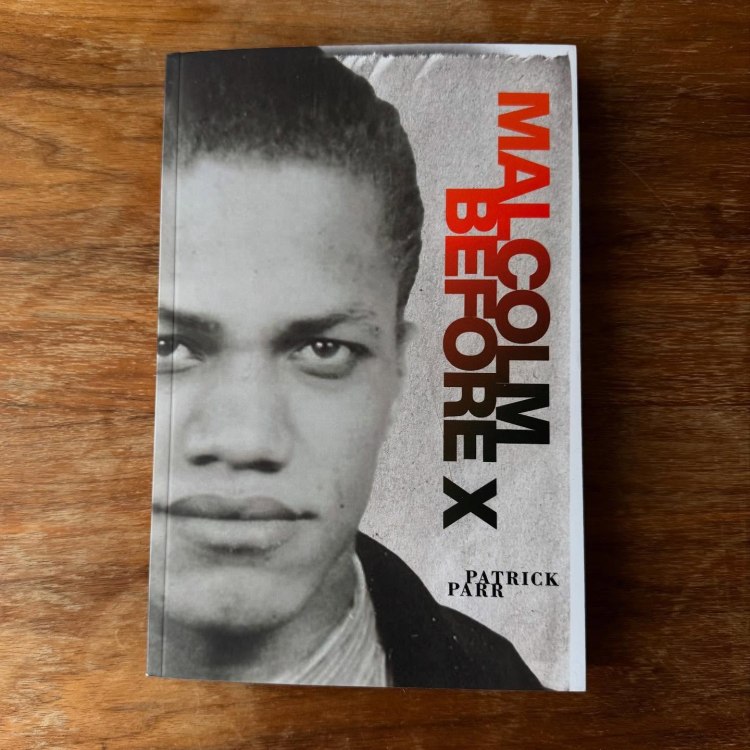

Published in 2024, Patrick Parr’s “Malcolm Before X” is an important study of Malcolm X’s early life, his period of incarceration in particular. As the title indicates, the focus is on tracking the details of his life leading up to his turn to Islam through the Nation. Parr constructs his narrative through long overlooked or understudied sources. The insights that the author is able to derive are much appreciated. For instance, a much richer family history emerges. We read about the influences that his siblings had on him and their correspondence with him throughout the book. As for the work’s structure, Parr divides the monograph into two parts. Part I “Outside” opens with a chapter detailing Malcolm’s arrest, trial, and imprisonment, but then proceeds in the next three chapters to document his early childhood until 1946. Part II “Inside” continues from there to explore in its subsequent chapters his incarceration at different facilities and the changes leading to his conversion. For those wishing to delve deeper into Malcolm’s biography, this is an indispensable resource. Ramadan 2

Ramadan 3

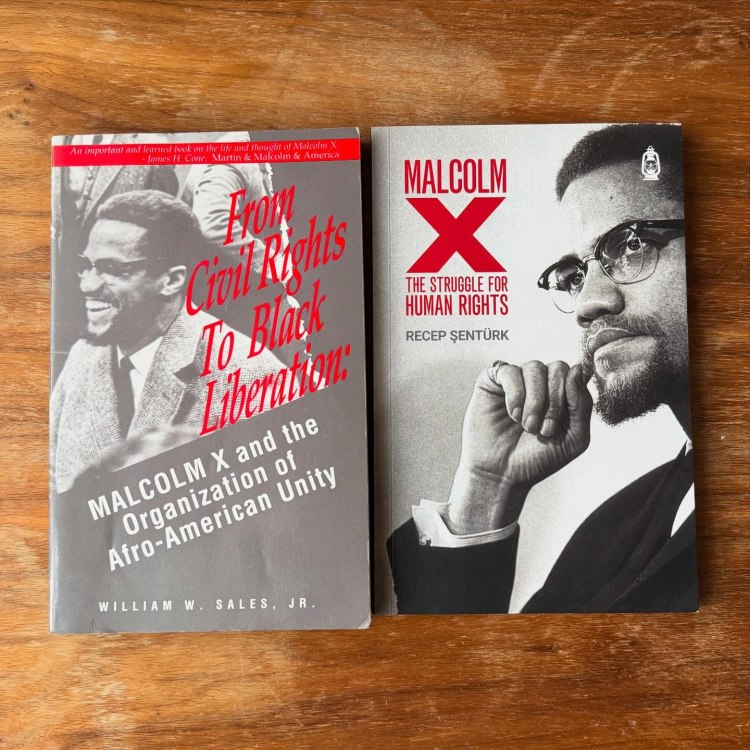

I’m featuring today two works on Malcolm X from years past that somehow escaped my attention. As I’ve been reading more concertedly about the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), which Malcolm founded near the end of his life, I came across frequent references to this work, “From Civil Rights to Black Liberation: Malcolm X and the Organization of Afro-American Unity” (1994) by William W. Sales, Jr. While the work is certainly a helpful look into the OAAU, Sales also takes the time to examine Malcolm’s legacy in general, opening with a look at his resurgent popularity in 1990 onwards. Next to it is a more recent work “Malcolm X: The Struggle for Human Rights” (2019) by Turkish sociologist and scholar Recep Şenturk. Published five years ago, I was embarrassed to only have learned about it now, especially given the fact that the author and I have met previously. Given the very different contexts of those academic encounters, our mutual respect and interest in Malcolm X had not come up. In any event, I’m glad now to have it and am looking forward to reading it some time soon insha’Allah. Ramadan 3

Ramadan 4

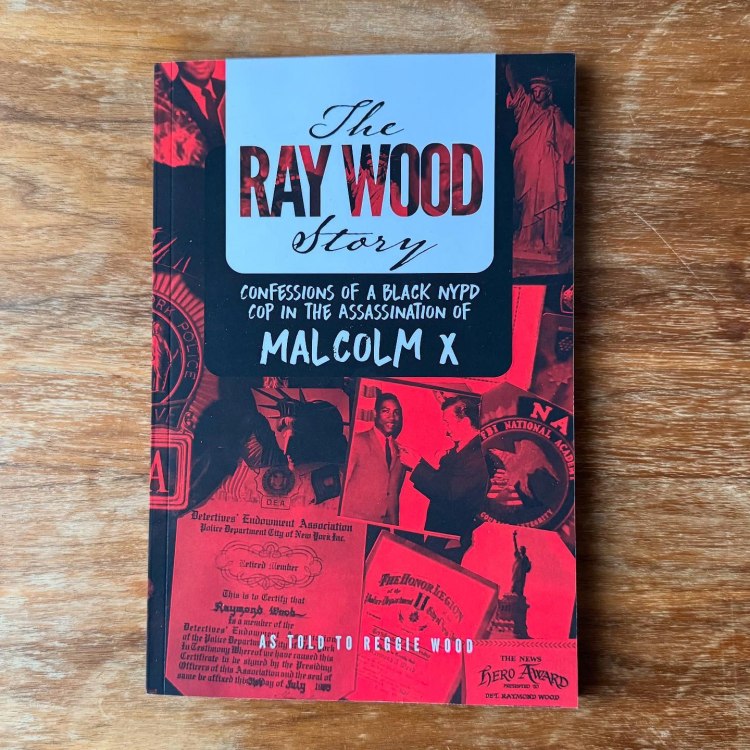

I have recently come to appreciate self-published titles. They are often quick to read and unburdened with specialist jargon and scholarly baggage. More often than not, the author simply has a story to tell and wants to tell it. This work, “The Ray Wood Story: Confessions of a Black NYPD Cop in the Assassination of Malcolm X” (2021), is one such example. It is not written by Ray Wood, but was composed and published after his death in 2020 by his nephew Reggie Wood, in whom he confided, and Lizzette Salado not long after. Ray Wood joined the NYPD at a time when African Americans were still far and few in-between there. He joined, moreover, during the racial tumult of the 1964. As a result, as Wood relates, he was pressed into undercover work to root out movements and figures that the NYPD deemed “radical.” The heart of the book lies with the morally compromising work Wood was compelled to do to bring down these supposed suspect elements. First, he set up Herbert Callender, aka Makaza Kumanyika, of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to be arrested. Then he aided in framing and falsely testifying against members of the Black Liberation Front (BLF) in a plot to bomb the Statue of Liberty. One of the men arrested in this last sweep was Khaleel Sayyed, one of Malcolm X’s guards. Finally, at the insistence of men he believed to be FBI, he was ordered to observe covertly events at the Audubon Ballroom on February 21, 1965, which, to his shock, culminated with Malcolm’s assassination. Only afterward did he realize his role: Sayyed’s arrest was intended to weaken Malcolm’s security detail. Wood’s hand in these affairs would haunt him to his death and resulted in this posthumous work. I came to discover it only after listening to the excellent podcast “Empire City” by Chenjerai Kumanyika, the son of the above mentioned Makaza. As for podcast, it is an incredibly incisive listen the surfaces the sordid past and present of the NYPD. This modest volume, when read alongside it, deepens that critical narrative. Ramadan 4

Ramadan 5

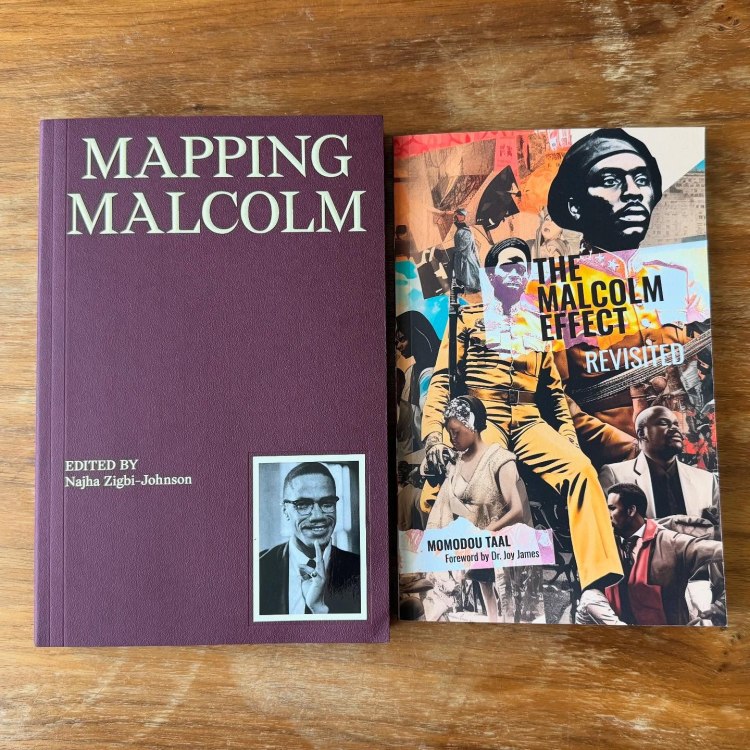

Here are two new works born out of Malcolm’s enduring legacy. Edited by Najha Zigbi-Johnson, “Mapping Malcolm” (2024) is a volume that brings together a dazzling array of pieces and essays on Malcolm. It contains far more than one might suspect. It looks like a conventionally bound paperback book, but upon opening it you’re treated to pages printed in a eye-catching maroon and cream, rather than the usual black and white. Indeed, the work is liberally interspersed with images and art. Among the pieces are artistically manipulated photographs of Malcolm, color reproductions of some of the postcards he sent to the Kochiyama family, news clippings, album covers, paintings, and many other visual artifacts. Perhaps most arresting was coming across Ossie Davis’s eulogy for Malcolm X, but copied out by Davis’s son, Guy, years later on sheets of yellow legal pad paper, just as has father would have done in the aftermath of Malcolm’s death and in preparation for the funeral. All in all, the book is both a beautiful tribute and a work of art. Alongside it is “The Malcolm Effect Revisited: Ruminations on Race, Religion, Gender and Political Economy” (2024) by Momodou Taal, which emerged out of his podcast of (nearly) the same name. Engaging a wide range of personalities, Taal shares brief excerpts of their responses on matters like Marxism, race, gender, and Islam. His interlocutors include voices like Cornel West, Judith Butler, Khaled Abou El Fadl, and Robin D.G. Kelley. Ramadan 5

Ramadan 6

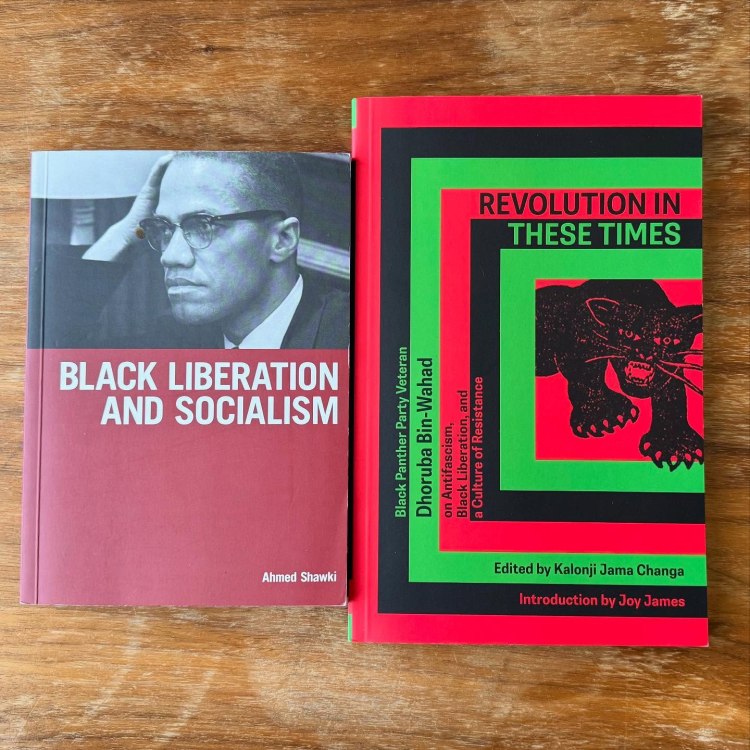

Ahmed Shawki’s “Black Liberation and Socialism” (2006) offers a sweeping history of movements across US history aimed at black liberation beginning with the era of slavery to the near present. Of its twelve chapters, chapter nine is dedicated to “The Politics of Malcolm X” that traces his arc through to Third Worldism. When Shawki speculates on Malcolm’s future trajectory he pushes back against claims that he seemed headed towards revolutionary socialism. Turning to Malcolm’s own words, Shawki argues for a more stayed, but also sounder reading of where Malcolm might have gone. This, of course, is only one part of the whole, which offers a highly readable historical account of socialism’s many roles and forms in the struggle for black freedom. With the time after Malcolm in mind, I also wanted to share, “Revolution in These Times: Black Panther Veteran Dhoruba Bin-Wahad on Antifascism, Black Liberation, and a Culture of Resistance,” (2025) edited by Kalonji Jama Changa (My thanks to Abdul-Rahman Malik for bringing this newly published work to my attention). The editor brings together and transcribes a series of compelling interviews in order to share the sharp political analysis and long experience in resistance and organizing of Dhoruba Bin Wahad, co-founder of the Black Liberation Army and member of the Black Panther Party. When asked about the seeming generational gap in movement work, he invokes Malcolm as part of his response, “People had to rediscover Malcolm. Why did they have to rediscover him? Because there was no movement left. People are rediscovering Assata. If they hadn’t put Assata up on a Ten Most Wanted list, we wouldn’t be having this conversation now. The enemy hasn’t forgotten what we are and what we could be.” (79) Ramadan 6

Ramadan 7

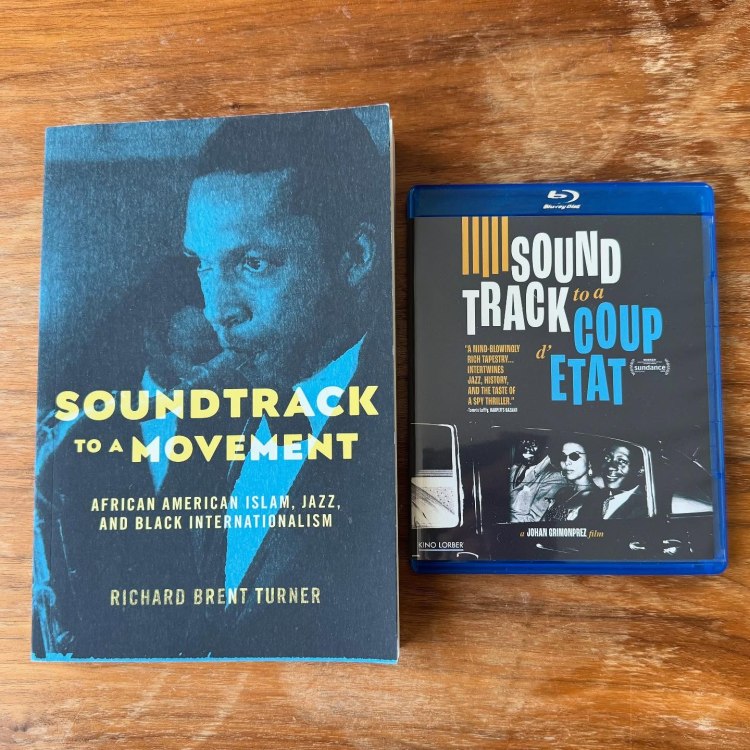

Jumu’a mubarak on this first full Friday of Ramadan. Today takes a musical turn and also features this series first film, I believe. First, the author of “Islam in the African-American Experience” (2nd Edition 2003), Richard Brent Turner, has published since then “Soundtrack to a Movement: African American Islam, Jazz, and Black Internationalism” (2021). In this captivating book, Turner does incredible historical work surfacing the many connections and enduring influences between jazz music and culture and the Black liberation movement here and abroad. He opens appropriately enough with Malcolm X and John Coltrane before launching into a rich and capacious history. This work pairs incredibly well with a recent documentary first recommended to me by Iman Aboulkarim. I’m referring to Johan Grimonprez’s “Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat” (2024). While a documentary, it is completely unlike any documentary I’ve seen. Frenetic with juxtapositions at first, it quickly draws you in. There’s no narrator, only the soundtrack and the many clips and quotations spliced within. But with that said, I still struggle to find how to characterize this work other than, perhaps, that the film itself is a kind of jazz assemblage. After all, jazz is the throughline that binds together a narrative of anti-colonial liberation where Patrice Lumumba rises to the fore but with but Malcolm X periodically appearing to offer his characteristic clarity. All the while the coup d’etat looms large, building in the background. I watched the documentary before Ramadan began, but I find myself still thinking about it these many days later. Like a song, its message soars and haunts. Ramadan 7

Ramadan 8

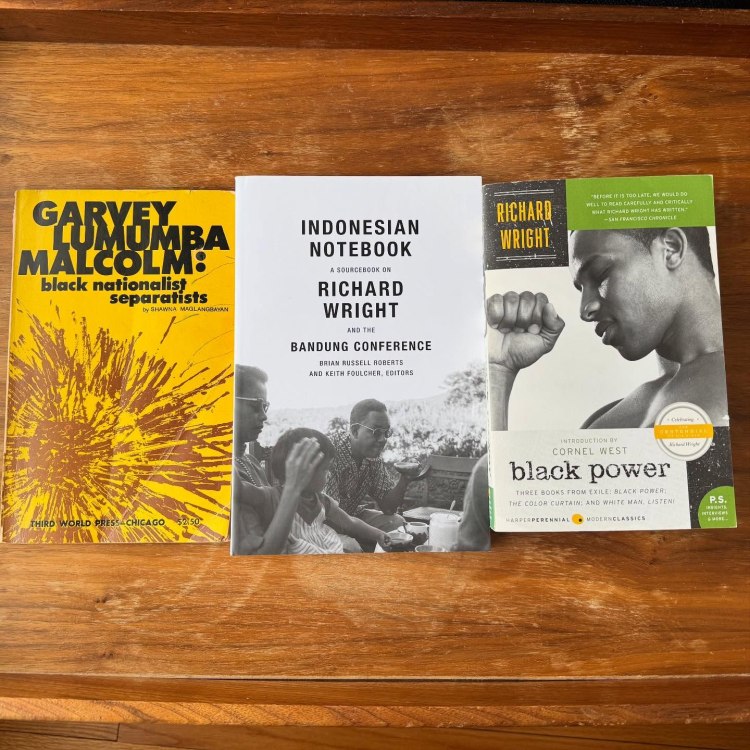

I wanted to share three works today. The first, as an older work, was challenging to find. Published by Third World Press, “Garvey, Lumumba and Malcolm: BLack National-Separatists” (1972) is a exploration of these three figures by Shawna Maglanbayan from a black nationalist-separatist lens. As she makes clear in the introduction, Maglanbayan is pushing back against white marxist distortions and co-optations of these men with her contribution. She offers instead an uncompromising reading (and at times critique) of how each figure worked towards Black liberation while rooted in an ethos of race consciousness. “In spite of the overhwelming obstacles put in their way day in and day out, Garvey, Lumumba and Malcolm X remained faithful to their mission. Like their national-separatist predecessors, they came to see the salvation of the Black race as dependent upon the independent assertion of Black humanity along its own economic, political, cultural, military and ideological lines of development” (14-15). The other two books bring us to the 1955 Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, Indonesia. The gathering at Bandung served as a longtime touchstone for Malcolm X’s developing thought. He invoked it explicitly, for example, in his famous “Message to the Grassroots” in 1963. While it was a major inspiration for Malcolm, African American writer Richard Wright actually attended the conference. “Indonesia Notebook: A Sourcebook on Richard Wright and the Bandung Conference” (2016), edited by Brian Russell Roberts and Keith Foulcher, brings together a wide range of documents and articles, that bring further texture to the proceedings at Bandung but also how it shaped and influenced Wright himself. After all, Wright wrote about the proceedings in “The Color Curtain” (1956), which is one of the three works included in the Richard Wright compilation “Black Power: Three Books from Exile: Black Power; The Color Curtain; and White Man, Listen!” (2008). Ramadan 8

Ramadan 9

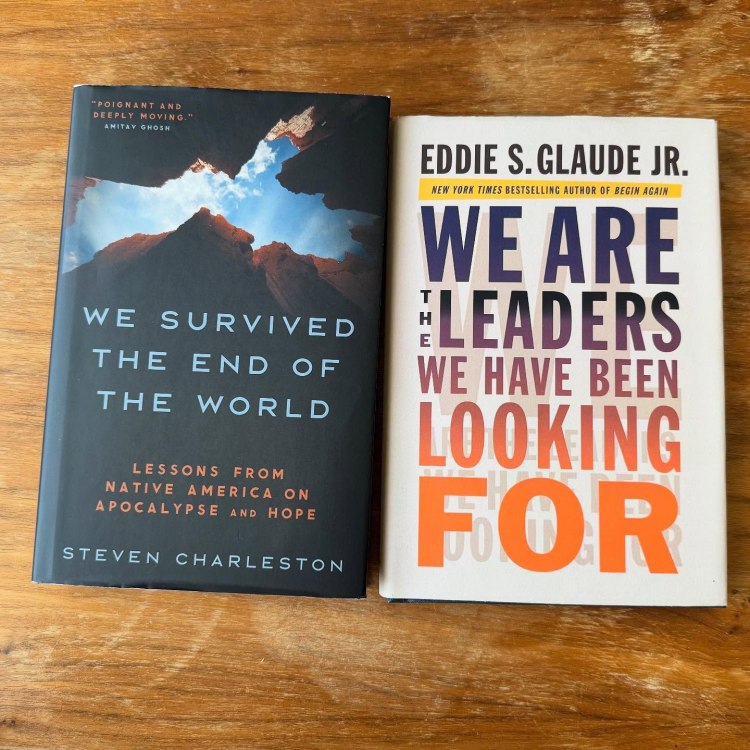

Here are two works that I read this past year. “We Survived the End of the World: Lessons from Native America on Apocalypse and Hope” (2023) is by Steven Charleston, a retired bishop of the Episcopal Church and member of the Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma. With a concern for prophetic theology, coupled with a desire to draw from the indigenous traditions of Turtle Island, Charleston shines a light on a set of Native American luminaries as they resisted and endured in their own respective ways the apocalypse of American settler colonialism. He does so as a means of informing how we might think, imagine, and act today. Over the course of this highly readable book he covers four figures – Ganiodaiio of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, Tenskwatawa of the Shawnee and brother to the Tecumseh, the Dreamer Smohalla of the Wanapams, and Wovoka of the Northern Paiute Nation – before turning to the Hopi Nation. It is an illuminating and inspiring look at another set of peoples living in what was the ending of their world. Eddie S. Glaude Jr.’s book “We Are the Leaders We Have Been Looking For” (2024) is a work that I purchased on impulse at an airport bookstore, something I genuinely rarely do. But flipping through its pages I realized I wanted to work through the narrative argument he was presenting, that we must rely upon or own labor and energy to enact the transformation we seek. He does this by guiding us through the wisdom and lessons offered by three historic personalities that sought to convey this during their own times: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Ella Baker. To quote but one passage: “Baker believed, and she enacted this belief in the way she organized, that what the Black freedom struggle needed most, what America needed most, was ‘the development of people are interested not in being leaders as much as in developing leadership among other people.’” (80). Both books, I have found, speak exceedingly well to our times. Ramadan 9

Ramadan 10

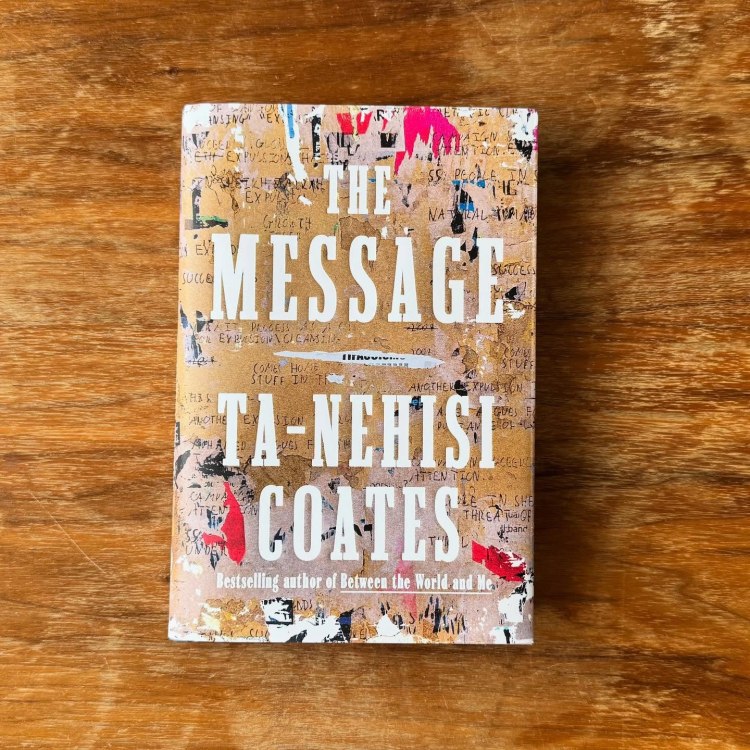

In April of 2024, I was able to attend a talk that Ta-Nehisi Coates delivered at Yale. Having read and listened through “Between the World and Me” on multiple occasions I was keen to hear what he had to share at the event. He did not fail to deliver and read excerpts from what was, at the time, his forthcoming book “The Message,” which was published later that year. While a book about writing, he takes us to a variety of locales, from his classroom at Howard University to South Carolina, where there are efforts to ban his book, to Dakar, Senegal to finally Israel/Palestine. While each chapter is deeply engaging, it is his last chapter which contains his lengthiest and most sustained dive, the chapter that explores his transformative experience in the last of these locales. It is was from this chapter that he spoke back in April – something that was sorely needed given the moment. As expected, his prose throughout the book is potent and mesmerizing. “An inhumane system demands inhumans, and so it produces them in stories, editorials, newscasts, movies, and television. Editors and writers like to think they are not part of such systems, that they are independent, objective, and arrive at their conclusions solely by dint of their reporting and research. But the Palestine I saw bore no resemblance to the systems I’ve known, that I am left believing that at least here, this objectivity is self-delusion” (230). Ramadan 10

Ramadan 11

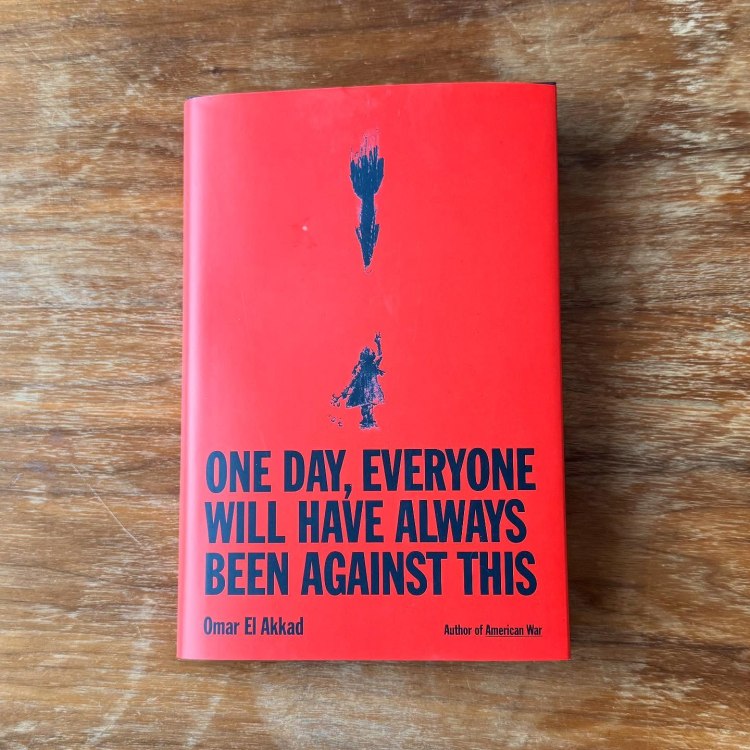

This work is a fresh arrival so I have not yet had time to plumb its depth, so to speak. “One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This” by Omar El Akkad (2025) was born from a tweet that the author published back on October 25, 2023. The work traces the structural oppression at the heart of the West by looking at the record of its moral failures from the past two decades and beyond. At the same time, elements of memoir inform the book’s shape and trajectory. Here is a powerful excerpt from its opening section: “As the men carry the girl out of what used to be her home, she asks if they’re going to take her to the cemetery. One of the men says, Mashallah, mashallah. In literal translation, the words mean: What God wills. A closer approximation of meaning – of one meaning – is something like: What has happened is what God willed. But English, tasked with a word like this, turns stiff and monophonic, and Mashallah is orchestral. To any ear that grew up with this language, it is clear that what the man means when he says this word is something else entirely. Something instantly familiar to generations who’ve heard it spilling out of mouths of beaming grandmothers at the end of piano recitals and graduation ceremonies and at the first sight of a newborn. Used this way, it finds its principal purpose, as an expression of joy. Look at this wonderful thing God has done.” (4-5). Ramadan 11

Ramadan 12

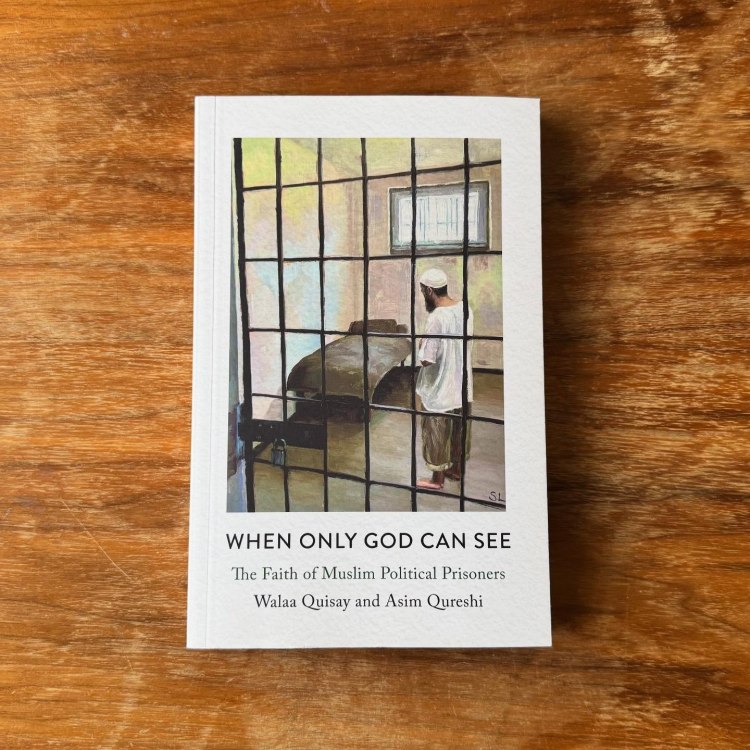

I had to read this work slowly. I had to read it one piece at a time. I had to set it down between readings so I could let its testimonies sit with me, so that I could understand their experiences as best I could, but more importantly, I just needed time to recover. Walaa Quisay and Asim Qureshi bring the accounts of so many Muslim political prisoners together in “When Only God Can See: The Faith of Muslim Political Prisoners,” published in 2024 by Pluto Press. Turning to the testimonials of those held in Egyptian prisons or US detention sites, they weave together a loosely knit, moving, and compelling carceral theology. It is needed work and they’ve done it superbly well. Even in the bleakest situations, faith glimmers through and acts of devotional resilience and resistance irrupt forth in inspiring and prophetic ways. The work as a whole offers an vital window into understanding theology from the ground up – from a ground of injustice and suffering to an extreme degree. While the accounts of faith illuminate, it is the brutality of their subjugation that gave me so much pause for here is also a stunning display of inhumanity of those holding the keys. To this end Quisay and Qureshi articulate the “theology” of the state that not only allows such inhumanity, but fosters it – feeds upon it. A sense of this comes from one testimony from Tora Prison in Cairo: “Outside, he would recall, the officers turned on loud, grainy Qur’an recitations from the radio to cover up the faint screams of the prisoners being tortured. Still he would hear the screams blurred in with the verses of the Qur’an” (38). This is what concerned the angels so. Ramadan 12

Ramadan 13

Here is a work of immense significance for the field of Islamic Studies, though its interventions are needed across the academy in general. Indeed, it joins a growing literature on the subject. The work in question is Kecia Ali’s “The Woman Question in Islamic Studies” (2024). Several years ago, the author delivered a keynote address at an evening reception of the American Academy of Religion. The room was packed and Ali’s message was clear: gender biases plague the works of our field. The problem was structural and evident in the citations, in-text references, and bibliographies to which our scholarly class so carefully tends. The present work, the result of years of reflection and interrogation, presents the case more methodically and fully than that earlier articulation. Since the raising of this question I have been more intentional but how I go about my own work, thinking about who I’m reading, drawing upon, and in conversation with, but I’m also aware that that is just a start. Far more is required. The issue is more extensive reaching down into how we form ourselves in the broader fabric of the academy. In any event, for any who are venturing into this scholarly field (or any other frankly), they’ll find Ali’s work requisite, but also engaging. Ramadan 13

Ramadan 14

This is the only novel I’ll be sharing this Ramadan, but it is one to behold, Marilynn Robinson’s “Gilead” (2004). I had picked this up a couple years ago after having heard of how good it was. After all, Robinson won the Pultizer in 2005 for it. I never got around to reading it, however, until last year. I finally turned to it after Danish Khan recommended it with enthusiasm. It did not take long for me to be engrossed completely by it. The work, set in 1956, centers on an aging preacher in Iowa, in the fictional town of Gilead, as he passes through his twilight years. With his mortal end in sight, the book represents, in fact, a lengthy letter that the preacher is penning for his still quite young son, a mere seven, to be read when he comes of age and well after his father has passed. I would describe the work as a wisdom novel, yet it is equally infused with humility as well. It is also a remarkable story of faith as felt and shaped in the wounds of human relationships. It stands now among my most beloved novels. Robinson is a gifted writer, I only wish I had discovered this work of hers earlier. Ramadan 14

Ramadan 15

Yesterday, I shared my late discovery of Marilynn Robinson’s work. Today I share yet another brilliant writer I come to far too late, poet and essayist Wendell Berry. A celebrated writer on nature, agriculture, and the environment I was intrigued by his many collection of essays. When I learned he had written a long essay on race, “The Hidden Wound” (1989), I decided to begin there (which I’ve learned since then is an unconventional place to start!). The beginning is bit wending and I wasn’t quite sure where it would lead, but in the end Berry delivers a compelling meditation on race, how it ruptures our connection with the land, and how we might overcome it through a particular kind of turn to community. The book ought to be read to understand Berry’s argument, but let me share this passage to help explain the title: “I have been unwilling until now to open in myself what I have known all along to be a wound – a historical wound, prepared centuries ago to come alive in me at my birth like a hereditary disease, and to be augmented and deepened by my life… If white people have suffered less obviously from racism than black people, they have nevertheless suffered greatly; the cost has been greater perhaps than we can yet know. If the white man has inflicted the wound of racism upon black men, the cost has been that he would receive the mirror image of that wound into himself. As the master, or as a member of the dominant race, he has felt little compulsion to acknowledge it or speak of it; the more painful it has grown the more deeply he has hidden it within himself. But the wound is there, and it is a profound disorder, as great a damage in his mind as it is in his society” (3-4). Ramadan 15

Ramadan 16

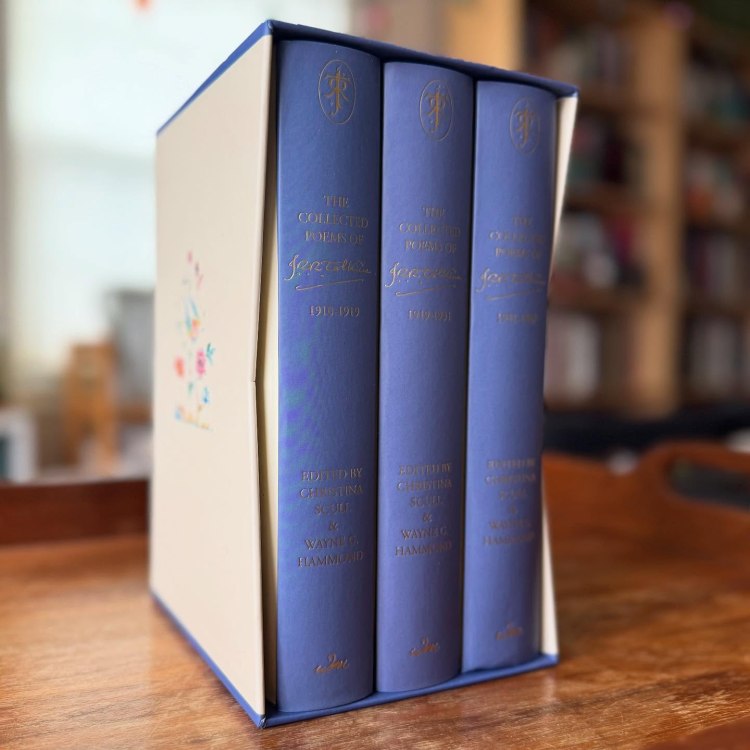

Despite J.R.R. Tolkien passing away in 1973, the field of Tolkien scholarship continues to unfold in remarkable ways. For decades his son Christopher spearheaded the editing and posthumous publishing of many of Tolkien’s unfinished works. Yet, even after Christopher Tolkien’s relatively recent death in 2020, scholars continue to compile, edit, annotate, and comment upon the Professor’s (as Tolkien is endearingly called) corpus of works. Here is the recently published three-volume box set of The Collected Poems of J.R.R. Tolkien” (2024). Edited by recognized Tolkien experts Christina Scull and Wayne G. Hammond, the set gathers together nearly seven decades of the Professor’s poetry documenting carefully the many versions found across his manuscripts and published works, even from the more obscure venues. While collections of his poetry have appeared before, this represents the most complete and exhaustive compilation now available, 195 unique poems in all. One of my favorite poems is “The Voyage of Éarendel the Evening Star” (1:86-97), which was first composed in 1914 and was inspired by a single line of Old English poetry that Tolkien had come across:

Eálá Éarendel engla beorhtast

Ofer middangeard monnum sended

The Professor translated those lines as “Hail Earendel, brightest of angels, above the Middle-earth sent unto men” (1:92).

To the Professor.

Ramadan 16

Ramadan 17

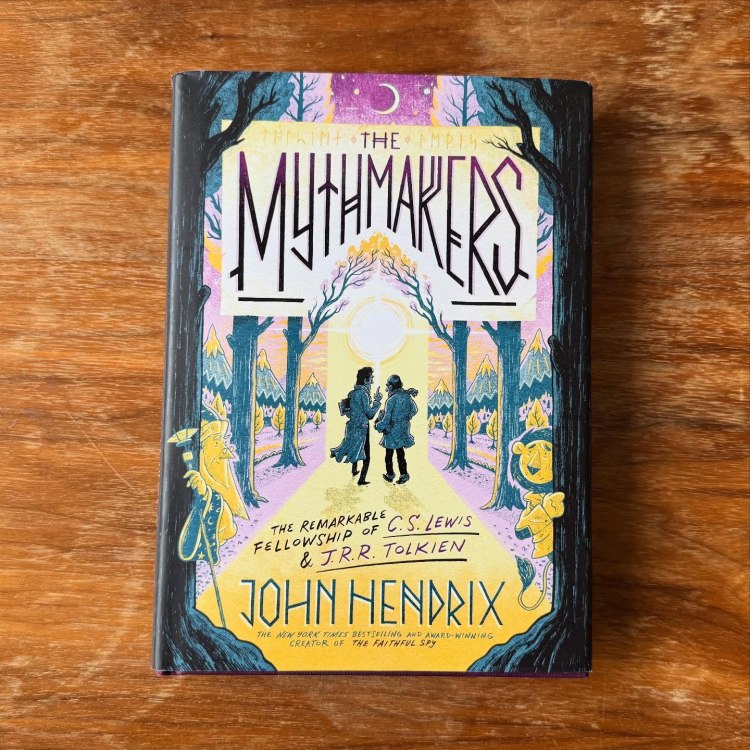

I can’t help but spend another day on something Tolkien related. Last year I was deeply moved by a graphic novel on the life and death of Christian theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, “The Faithful Spy” (2018). Its author, the talented John Hendrix has returned with a new graphic novel, which I have found equally compelling in its own way, “The Mythmakers: The Remarkable Fellowship of C.S. Lewis & J.R.R. Tolkien” (2024). It is beautifully illustrated and framed in a enchanting manner, yet still manages to seamlessly weave within its pages substantial doses of biography and exposition. This is all executed in a marvelously balanced way. Hendrix not only shares with us the nature of these two men’s lives and their extraordinary relationship with one another, he also presents the significance of myth in a stunningly relatable and accessible way. At its heart, this is a work about faith and imagination. It is a worthwhile foray into something beautiful and affirming – a source of inspiration in time when inspiration is much needed. Ramadan 17

Ramadan 18

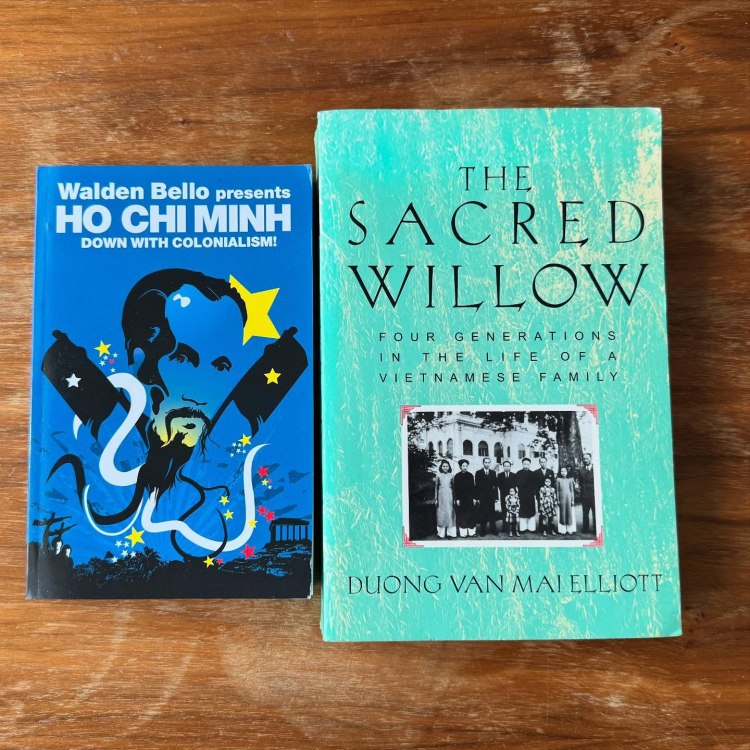

This past fall I traveled to the land of my origins, Vietnam, for the first time. It was a powerful experience that I still haven’t been able to write about, though the words are ever finding and forming themselves. Rest assured, I did an immense amount of reading and research in preparation for that trip. And one day, I may catalogue the many works that I combed through to that end. There were two works, though, that I did not pick up until after my return that I found immensely helpful in processing and coming to understand some of the things I saw. The first is “Down With Colonialism!: Walden Bello Presents Ho Chi Minh” (2007), which collects many of the writings and speeches of Ho Chi Minh, the revolutionary leader that worked to bring about the independence and unification of the present nation. Reading his words added a much needed layer of depth to the history that is enshrined and on display strategically across the country. Even more helpful, however, is Duong Van Mai Elliott’s magisterial “The Sacred Willow: Four Generations in the Life of A Vietnamese Family” (1999). Weighing in at over 450 pages, I put this work off until after my return because of its intimidating size. In it, the author offers a deep and intimate look at her family’s long history, which also brings to life those critical periods of history before French colonialism, through it, to the wars for independence that bring us to the near present. Although the work requires time, it has been the most rewarding read for understanding the long struggle that Vietnam and its people have had to undergo. Ramadan 18

Ramadan 19

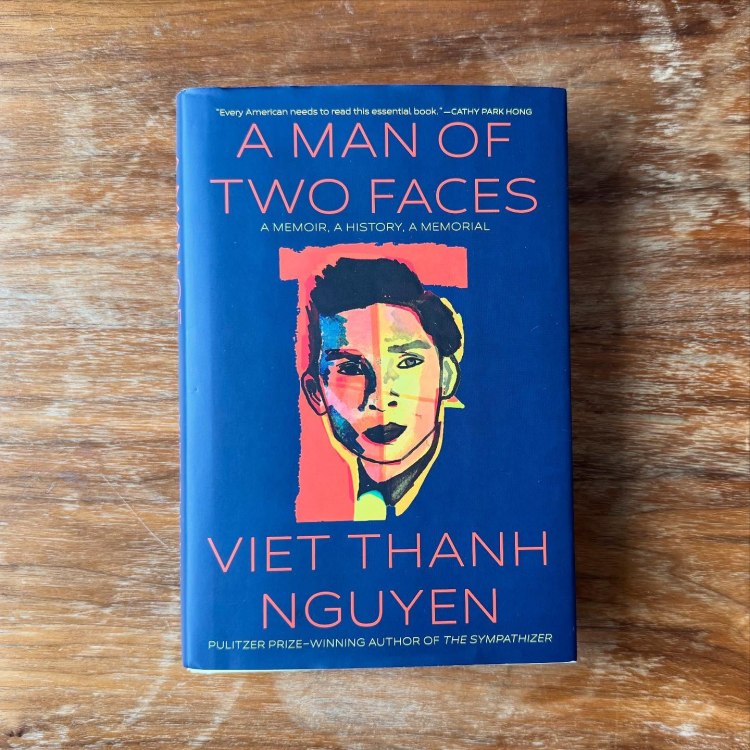

I return to one of my favorite writers, Viet Thanh Nguyen, whose Pulitzer prize winning novel “The Sympathizer” I covered way back in 2020, my first year doing this series. Since then, I’ve read the sequel “The Committed” and watched the HBO series of “The Sympathizer” (brilliant in its own way). Today, however, I am turning to Nguyen’s latest book, “A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial” (2023). In it he takes us through the seasons of his life as a refugee, a son, a writer, a father, and more. Its prose is fragmented, but in a lyrical fashion that weaves together poetic reflections with incisive and critical observations. Given my own background, this work has resonated with me profoundly. I could feel echoes of my own life in its words. Here’s a sample of what lies within:

“You acquire a voice,

but you do not know

it is not your own.

It is the voice of someone imitating the masters of Theory. To outsiders, Theory often appears dense, complicated, opaque. But your twentysomething self is genuinely inspired by the conviction that theorizing is a way of plunging beneath the surface of texts, things, the world, to understand how art, power, and politics operate. You set out to master this discourse that criticizes the world through criticizing the text.

By the end of your doctorate,

the discourse masters you.” (259)

Ramadan 19

Ramadan 20

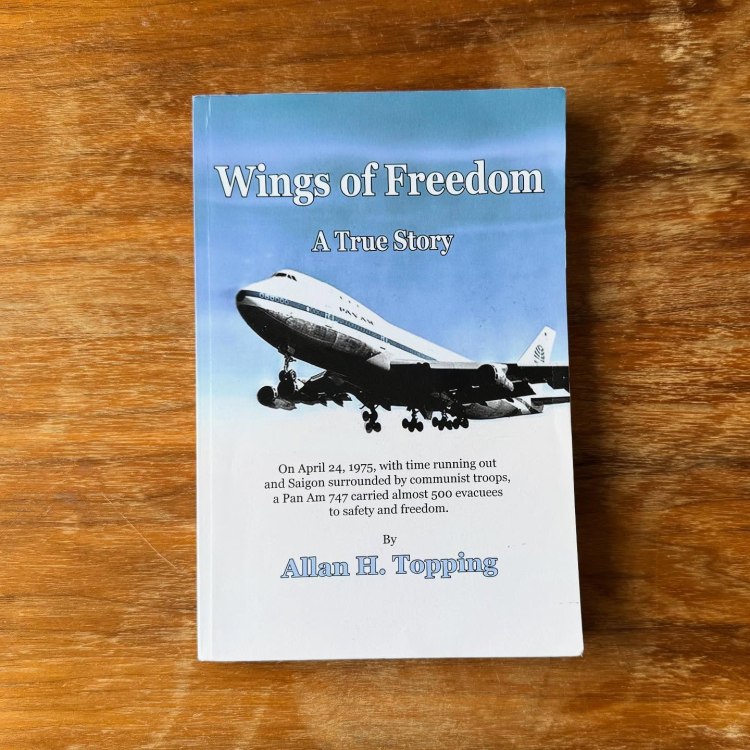

My mother had always mentioned that she had escaped on a Pan Am flight out of Saigon as the city fell in 1975. As I learned more details and did my own research into this moment of history, I realized that she had not just left on a regular flight, but departed on April 24th on the last civilian flight out of South Vietnam. Then, as I followed this thread I learned that Allan H. Topping, who was the Pan Am Director of Cambodia and Vietnam at the time, had self-published a memoir that covered this time and detailed his critical role in making this final flight happen. I ordered and read “Wings of Freedom: A True Story” (2020) eagerly. In it I learned that Topping was committed to ensuring that every employee of Pan Am in Saigon could evacuate with their loved ones. My mother’s brother was one of those employees at the time, which allowed my young mother and her family to escape six days before the city fell. Topping writes of that flight, “We had almost 500 people on board the airplane. People were on the floor, in the aisles, in the lavatories and, due to the typical small frames of the Vietnamese people, it was not a problem for some to be two in a seat… Once we reached our cruising altitude, I walked through the cabin again to see how everyone was coping with what had just happened. It was a sad moment. There were many tears, expressions of fear and sadness on their faces. Eyes glazed over. Understandably, their mood was somber, mixed with hope about how their lives, in just a manner of hours, would never be the same again” (76-78). My mother, only twenty at the time, was one of those souls. I have since written to Allan Topping to express my gratitude that he took the time to share his story as it carries a part of my family’s story as well as so many others. Ramadan 20

Ramadan 21

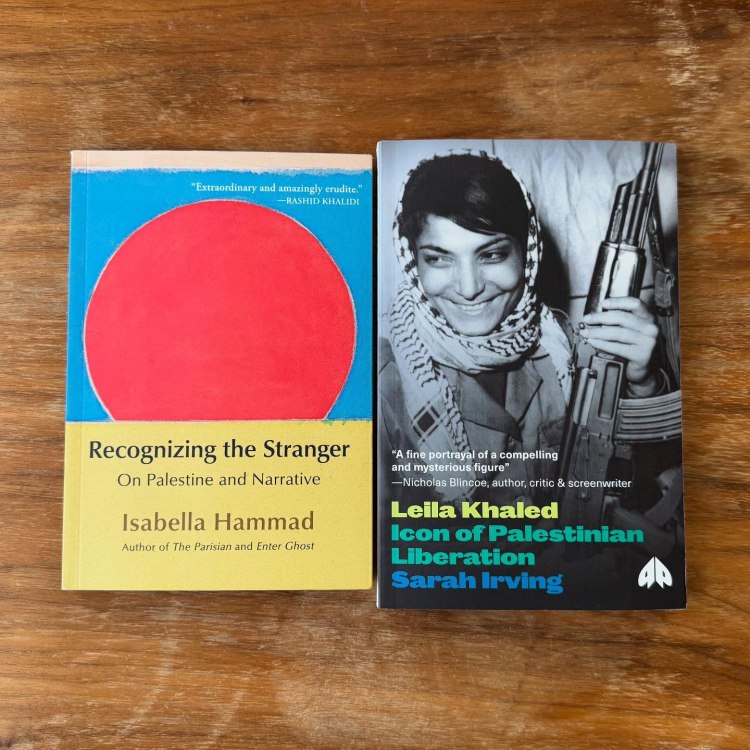

From Vietnam and its past struggle for independence I now turn to Palestine in our present. “Recognizing the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative” contains the words that author Isabella Hammad delivered for the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She writes: “Rather than recognizing the stranger as familiar, and bringing a story to its close, Said asks us to recognize the familiar as stranger. He gestures at a way to dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd groups. This might be easier said than done, but it’s provocative – it points out how many narratives of self, when applied to a nation-state, might one day harden into self-centered intolerance” (56). At the book’s conclusion is a newly added Afterword that discusses events since the lecture’s delivery. Next to it is a work that I have yet to read, though I’ve read other works in this biographical “Revolutionary Lives” series from Pluto Press. Sarah Irving’s “Leila Khaled: Icon of Palestinian Liberation” (2012) is a concise look into the life of Khaled who famously hijacked a plane in 1969 and quickly rose to public prominence. Irving moves beyond the historic headlines, however, following Khaled’s life journey down to the near present. I selected these works in the weeks before Ramadan. Much to my surprise, several days ago on March 17th I read that Leila Khaled, who lives in Jordan, had been hospitalized for a brain hemorrhage. May God grant shifāʾ. Ramadan 21

Ramadan 22

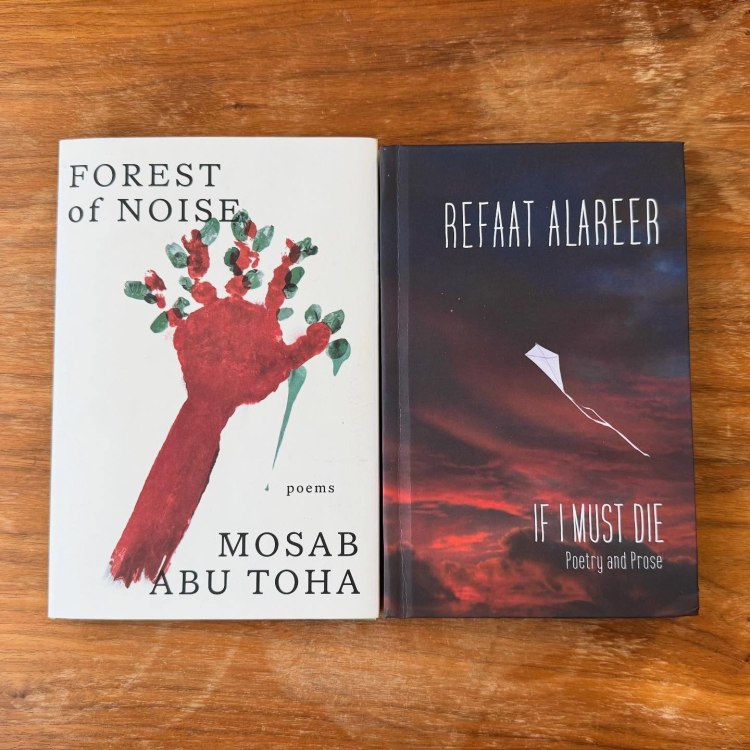

I had the good fortune of hearing Musab Abu Toha speak at our local and incredible community bookspace Possible Futures last year. There he kindly signed my copy of his earlier poetry collection “Things You May Find Hidden In My Ear” (2022). On the front page he inscribed “Palestine is only a poem away.” I thought it appropriate then to share today two works containing Palestinian poetry. Not long after his visit Abu Toha’s “Forest of Noise” (2024) was published. His opening epigraph reads:

Every child in Gaza is me.

Every mother and father is me.

Every house is my heart.

Every tree is my leg.

Every plant is my arm.

Every flower is my eye.

Every hole in the earth is my wound. (ix)

Accompanying this work is a collection from Abu Toha’s friend and fellow poet Refaat Alareer, who was killed on December 6, 2023 in what the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor reports as a targeted strike. In the wake of his death, his poem “If I Must Die” captured the hearts of many worldwide. It seems appropriate then, that his posthumously published book is entitled “If I Must Die: Poetry and Prose” and brings together many of this incisive pieces and poems. Here are the last lines from the 2012 poem “And We Live On…”:

We dream and pray,

Clinging to life even harder

Every time a dear one’s life

Is forcibly rooted up.

We live.

We live.

We do. (73)

Ramadan 22

Ramadan 23

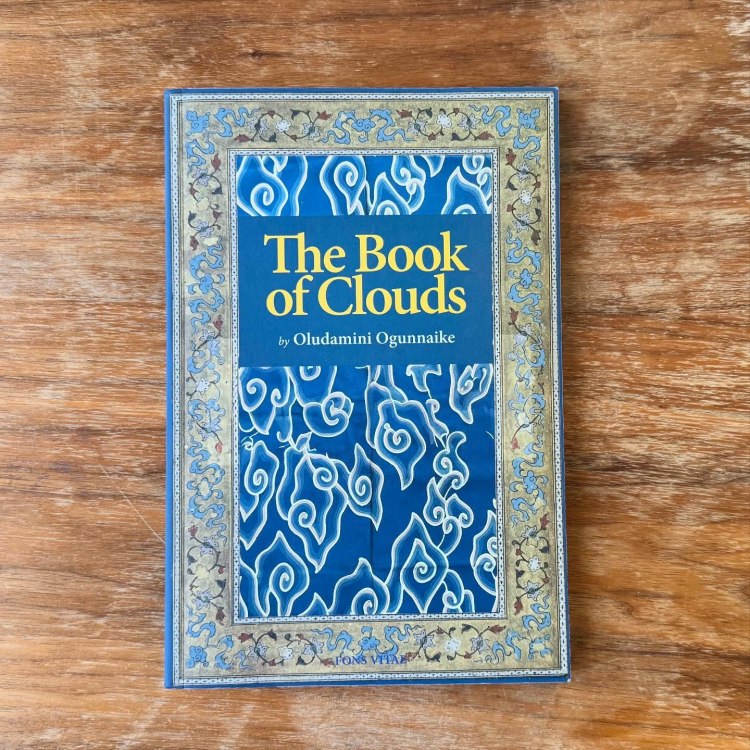

Here is a remarkable collection by Oludamini Ogunnaike, “The Book of Clouds.” It is a book of poems that draws upon the breadth and breath of the tradition. Ogunnaike turns to qasidas, ghazals, and more in this capacious and inspired work. In the Preface he explains:

“But the poems of this diwan are not a literary exercise, they were born from a kind of inward necessity and pressure to work out grief, bewilderment, longing, love, delight, gratitude, and insights in body, mind, and soul at once, which is to say, in poetry. Good poetry moves us from the depths of our hearts to the tips of our hairs, and its medium is our very living breath” (xix). Here is an excerpt from “An Elegy for Migrants”:

But the desert swallows tears

water gone, the salt remains

Body bags have all been zipped

leaving valleys deep with pain

Paths well-trod by shoeless feet

mark out all the unmarked graves

Headlines echo like thunder

dark clouds leaving without rain

Numbers hail upon the page

always numbers without names

Names are whispered in the wind

last breaths swirl to hurricanes

Prayers like lightning flash up-down

cutting through the sky’s dark waves

Many who crossed on were drowned

many who drowned there were saved (110)

Ramadan 23

Ramadan 24

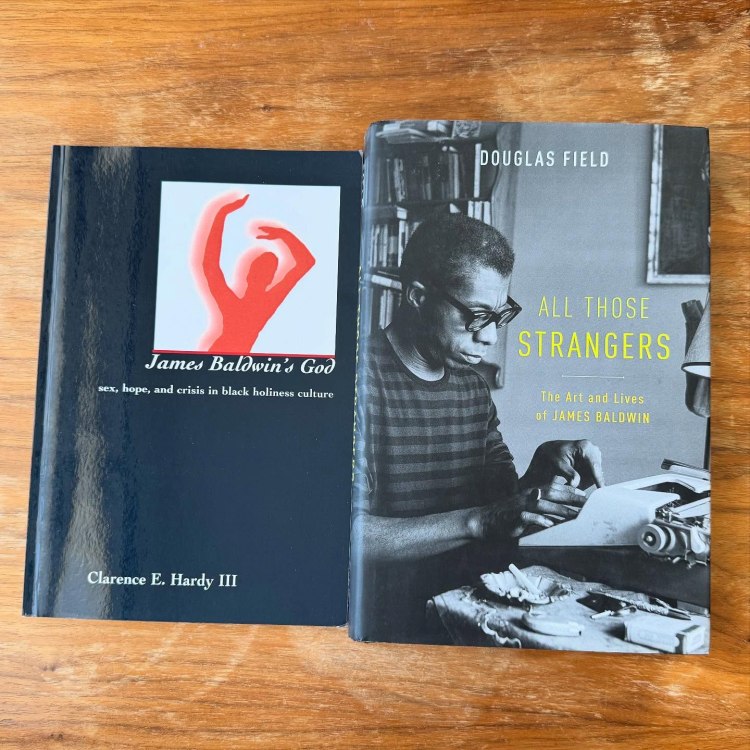

It is about time I spend some of this month with James Baldwin. I’ve chosen the works that I’m featuring today for the light they shed on Baldwin’s relationship to religion. The first book is by my colleague and friend Clarence Hardy, “James Baldwin’s God: Sex, Hope, and Crisis in Black Holiness Culture”(2003). Working through Baldwin’s writings, Hardy guides us through the complicated relationship that Baldwin had with Christianity, the black church, and black holiness culture in particular. Here is an excerpt from the conclusion: “I know for myself that the music and drama of black religion – of conversion-brokered religion – can have quite a grip on the human personality. Its hold can be so firm that even Baldwin, who found black institutional Christianity more compromised than I, found within its cultural expressions a posture of humanity, if not always one of overt resistance, that has enacted an admirable measure of strength, community, and identity” (115). Douglas Field’s “All Those Strangers: The Art and Lives of James Baldwin” (2015) also considers religion, at times building explicitly on Hardy’s work (especially in Chapter 3). The book, however, zooms out to situate Baldwin’s expansive life against the various political currents that coursed through the decades of his existence. It is a study of Baldwin set against both geography and history. It is a study that brings to life the many Baldwins that were. Ramadan 24

Ramadan 25

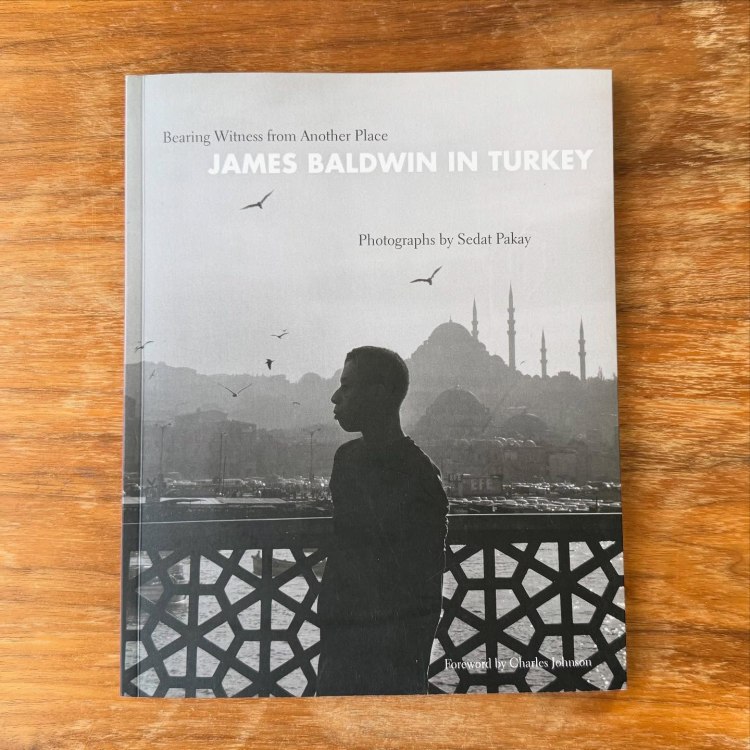

In my journey into James Baldwin’s life and words, the most surprising – but welcome – discovery was that he had spent nearly a decade living in or frequenting Istanbul. In 1970, near the end of that time, Turkish photographer and filmmaker Sedat Pakay shot a 12-minute documentary of Baldwin in the city entitled “James Baldwin: From Another Place.” I then learned that Pakay’s photographs, which are often exhibited, were eventually published as part of a book to accompany an exhibition arranged by the Northwest African American Museum, “Bearing Witness from Another Place: James Baldwin in Turkey” (2012). This proved to be an incredibly challenging work to find, but after a fair measure of diligence and patience I was able to obtain a copy. The search was worthwhile. Edited by Kathryn Hubbard and Barbara Earl Thomas, the slim, but striking volume contains many of Pakay’s photographs arrayed alongside a series of reflective, thoughtful, and evocative essays. Ramadan 25

Ramadan 26

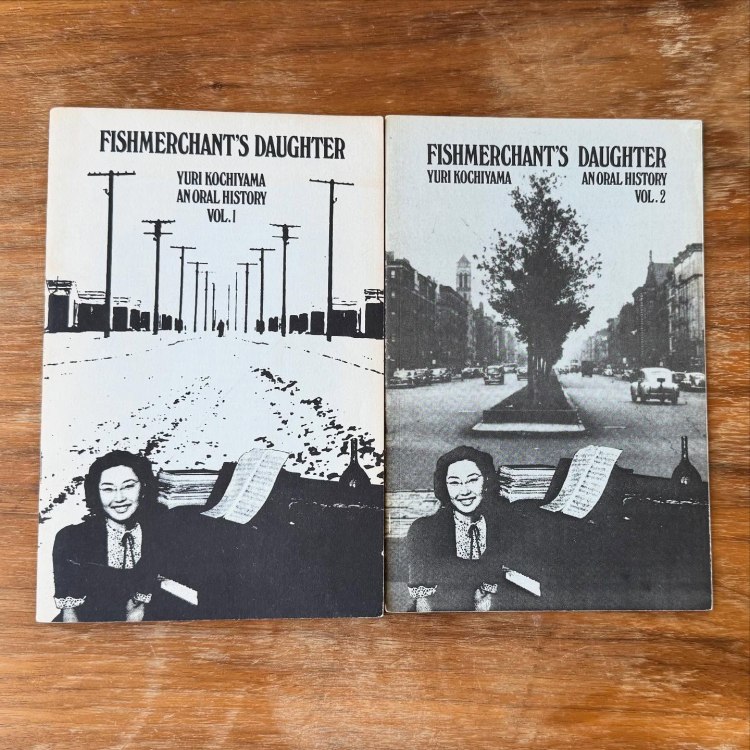

I recently started posting short essays and drafts of my work fairly regularly on substack. I’ve temporarily stepped away from it for the month of Ramadan in order to tend to this bookshare series. In that endeavor, I’ve spent quite some time exploring the remarkable life of Yuri Kochiyama, especially as it intersected with Malcolm X, though there is much to commend and commemorate beyond that. Incredibly helpful to that research were these two slim booklets, more like zines in length and binding. “Fishmerchant’s Daughter: Yuri Kochiyama, An Oral History” volumes 1 and 2 weigh in at a modest 30 and 19 pages each. What they contain are Yuri’s own words about her life from her early years in California to her internment by the US during World War II through to her later years in New York City. This oral history was recorded and edited by Arthur Tobier. The first volume appeared in November 1981 with the second following in 1982 from the Community Documentation Workshop at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery. While later biographical works exist, like Yuri’s own memoir “Passing It On” (2004) and Diane C. Fujino’s “The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama” (2005), both of which I shared back in 2021, these volumes of oral history represent Yuri’s recollections from more than two decades earlier, a markedly different point in her life. Having combed through all these works, it is clear that the “Fishmerchant’s Daughter” has much to offer by its own right. In any event, I cannot recommend enough the wisdom and lessons to be learned from Yuri Kochiyama’s life, deeds, and legacy. Ramadan 26

Ramadan 27

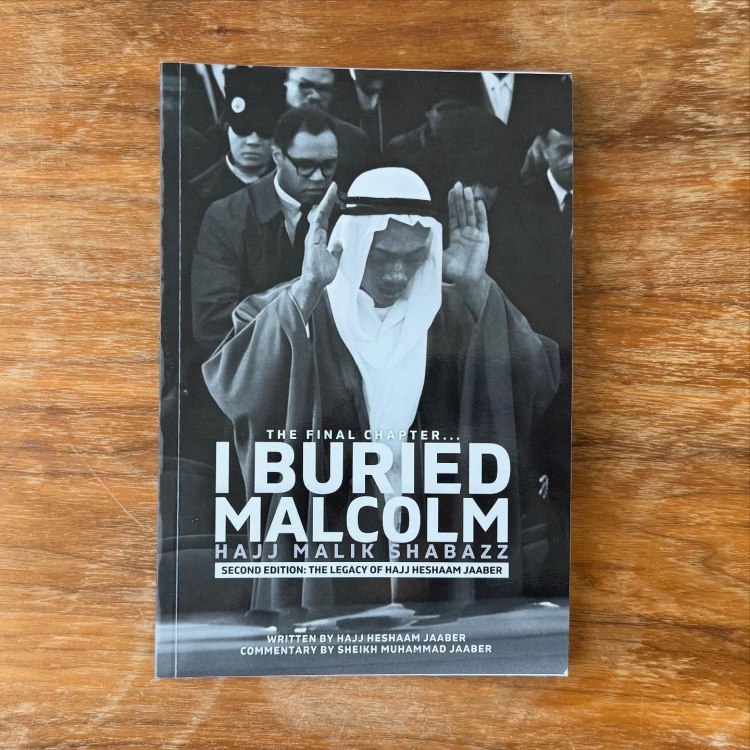

Last May I attend the Islamic Circle of North America Convention in Baltimore for the first time. While wending my way through the bazaar, I came across a table advertising a new book about Malcolm X and met one of its authors. That is how I can to learn of “The Final Chapter… I Buried Malcolm Hajj Malik Shabazz, Second Edition: The Legacy of Hajj Heshaam Jaaber” (2023). At the time, Sheikh Muhammad Jaaber kindly shared with me his story and that of his father Hajj Heshaam Jaaber, who (as shown on the cover) led the funeral prayer or janaza for Malcolm. The work was originally written by Hajj Heshaam Jaaber, who passed away in 2007, but now includes additional writings from his son Sheikh Muhammad Jaaber. At the start, Hajj Heshaam recounts his role in arranging a Muslim burial for Malcolm. The book then proceeds to provide an Islamic commentary upon Malcolm’s life while also containing the story of Hajj Heshaam Jaaber’s life as well. In this final segment, we learn that he was by Dr. Betty Shabazz’s side after the fatal fire that would take her life in 1997 and was a crucial part of her burial as well. Sheikh Muhammad writes: “From her hospital bed, Hajj Heshaam would lead her in prayer (Salaat) while she was only able to follow with the movement of her index finger” (212). I am grateful that these accounts, rather than be lost to time, have been preserved for generations to come. Ramadan 27

Ramadan 28

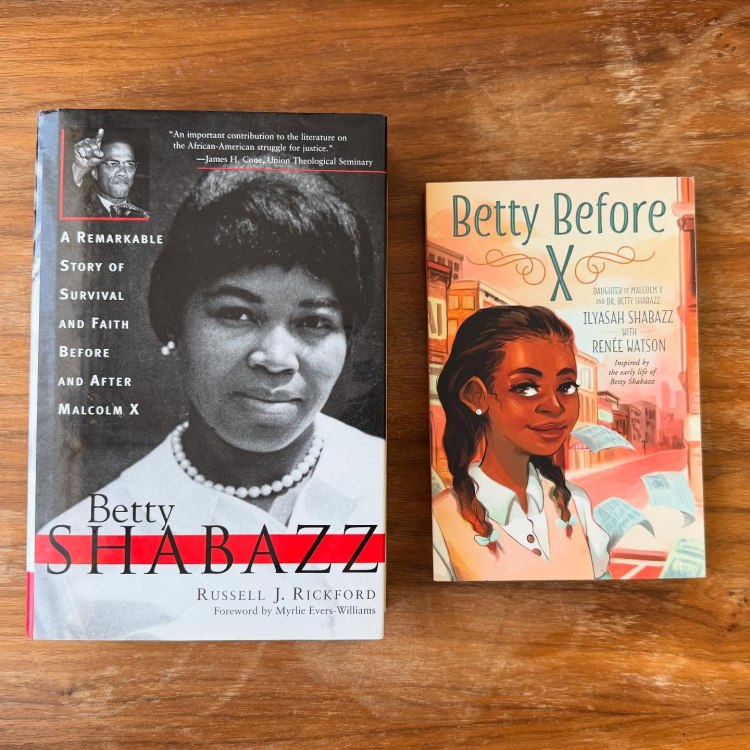

While the books dedicated to Malcolm X are abundant, voluminous even, works on Dr. Betty Shabazz number significantly fewer. Fortunately, new studies on her are beginning to emerge. Today I’m spotlighting two important works on that front. The first is a biographical tome on Betty Shabazz that has been around for some time, Russell J. Rickford’s Betty Shabazz: A Remarkable Story of Survival and Faith Before and After Malcolm X” (2003). It presents what I believe is the fullest account of her life and remains a valuable starting point for anyone wanting to delve deeper into her work and legacy. It moves beyond her time with Malcolm to document all that she accomplished after as well as shining a light on who she was before. Alongside it is a novel aimed at bringing Dr. Betty Shabazz’s earlier years to the fore for a younger audience, “Betty Before X: Inspired by the Early Life of Betty Shabazz” (2018). I’ve come to appreciate how accessible, poetic, and powerful young adult fiction can be. This work in particular is especially notably because one of Malcolm’s and Betty’s daughter, Ilyasah Shabazz, co-authored the book with Renée Watson. While promising work on Dr. Betty Shabazz is on the near horizon, these two books are certainly worthwhile in the meantime. And of course, as we take the time to honor Malcolm X, we should not forget the critical role that Betty Shabazz played and the many contributions that she made in her own right. Ramadan 28

Ramadan 29

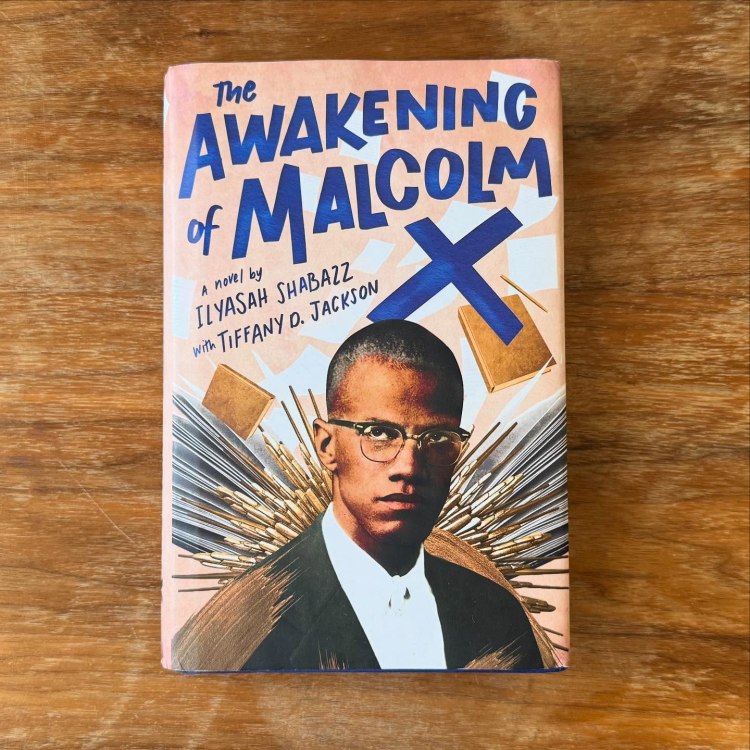

I’m still reading this book in anticipation of an upcoming book club meeting at my local bookspace, Possible Futures. But with the end of Ramadan here, I wanted to share this work as a way to honor Malcolm – to both open and close the blessed month with work on him in what would have been his 100th year. So here is “The Awakening of Malcolm X” (2021) co-written by his daughter Ilyasah Shabazz and Tiffany O. Jackson. Like the book yesterday on an imagined young Betty Shabazz, this highly readable book is also a work of young adult fiction. What makes the story so compelling is that it allows us to imagine Malcolm’s life narrative from a vector often overlooked or unplumbed – it is a narrative that gives voice to Louise Little, Malcolm’s mother, who played such a pivotal role in his formation, but whose place in his biography (and autobiography) are limited. This, then, is a work of restoration. It shines a light on a lacuna. It is a light worth following. May the story of Malcolm’s awakening feed and form our own awakenings in these fraught and trying times. Ramadan 29

Eid

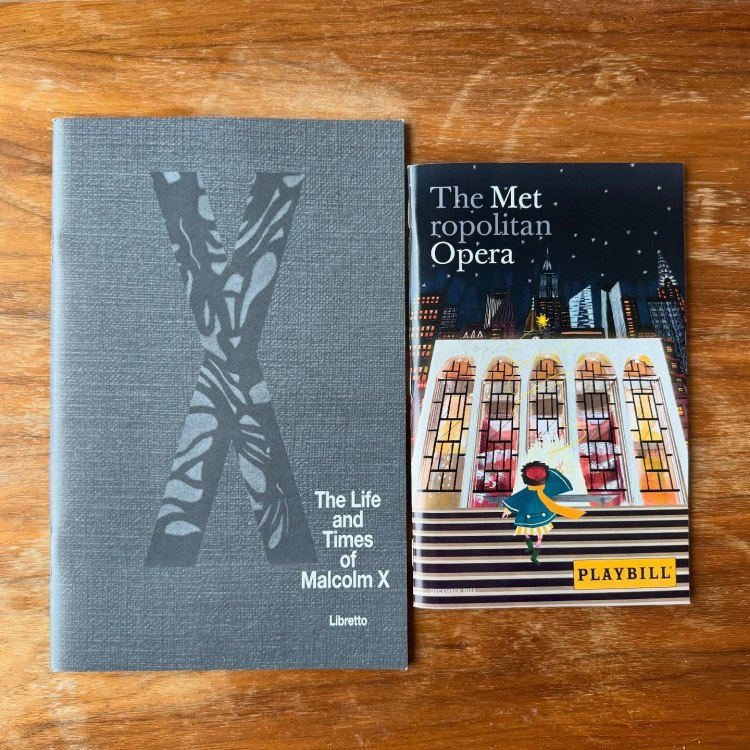

The ephemera of a time is often as important as its books. Here are two pieces I wanted to share in that respect. But first, some context… On December 2, 2023 I attended with close friends “X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X,” an opera performed at the Met at Lincoln Center. With music by Anthony Davis, libretto by Thulani Davis, and story by Christopher Davis, the opera was a genuinely remarkable experience – one that I am glad to have witnessed in person. It took a life familiar to me and delivered in a dynamically different and illuminating way. As for the piece itself, its life has been long. It was originally staged in Philadelphia in 1985 and then was revised the following year for its New York debut. On this celebratory day, then, I wanted to share some important ephemera from this remembered December of mine. Here is “X:The Life and Times of Malcolm X – Libretto” (2022) that contains the “Revised 36th Anniversary Edition” script as delivered on stage that memorable night. Set alongside it is the Playbill that accompanied the performance. With Eid here (or nearly arriving depending on your community), Eid mubarak to one and all. May the deeds and devotions of the past month be accepted and may this day and the days ahead be blessed. Eid